THE DANCE ENTHUSIAST ASKS: Kyle Abraham on his "Dear Lord Make Me Beautiful" Premiering at the Park Avenue Armory

"Dear Lord Make Me Beautiful" Runs from DECEMBER 3 - 14, 2024

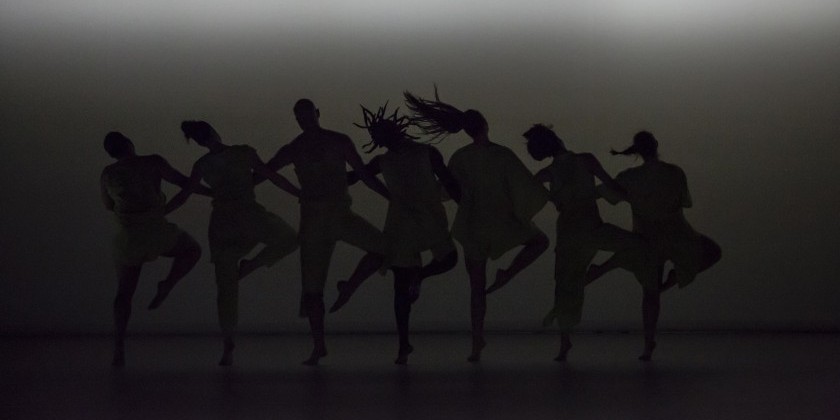

Acclaimed choreographer Kyle Abraham (A.I.M.) has long been celebrated for his ability to weave deeply personal narratives with larger cultural conversations crafting works that resonate across audiences and disciplines.

Known for blending contemporary dance with hip-hop and classical traditions, Abraham’s artistry reflects his Pittsburgh roots, his formal training at SUNY Purchase, and the profound influence of Black cultural history. A prolific choreographer who has worked with some of the world’s most renowned companies and dancers, Abraham could easily rest on his laurels, but instead he constantly seeks new influences and collaborations. This earnest commitment to personal growth as both dance maker and human – and the anxiety that can accompany this quest for self betterment– is the influence for his latest creation, Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful, set to premiere at the iconic Park Avenue Armory this December.

The work is also supported in part by Dance Reflections by Van Kleef and Arpels. The Dance Enthusiast’s Theo Boguszewski speaks with Abraham about his creative process, and the personal experiences that inspired him to explore these themes of beauty, identity, and vulnerability.

For Tickets: Click Here

Theo Boguszewski, for The Dance Enthusiast: Can you tell us about the inspiration behind "Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful"? What sparked the initial idea for this piece?

Kyle Abraham: A lot of my works reference an earlier time. You wrote about Pavement in 2016 – that's a work that, although it premiered in 2012, was looking at film and ideas rooted 20 years prior. But when I wrote the narrative for this piece in 2021, it was really about where I was personally in that moment, and what I was feeling. And that led to the work being rooted in ideas of empathy and aging and change. And nature's relationship with aging as well.

“Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful” was commissioned by the Park Avenue Armory. Did they give you any guidelines for what they were looking for in the work?

Well, they first reached out to me in 2018, and we had several years of back and forth just trying to find the right project. One of the only things that Pierre [Audi] wanted me to consider was making something that had to have been performed in a space like the Armory. But also something that could tour in other spaces in the future. Which was a tough directive. There was also an interest in me working with live music, so we started thinking about what was the right kind of compositional makeup or score to be created.

Did you select the new music ensemble yMusic?

Yeah. I'd used their music over the years for different projects. In more recent years, they started composing their own music, and I was drawn to that process as well as the instrumentation that they tend to work with.

Can you share a little bit more about how you're planning to use the massive space of the Armory?

I think one of the big things for me is trying to find moments to focus on the individual. In a space like that, you can really highlight loneliness and feeling isolated, but hopefully in a beautiful way. It's just much more resonant in that kind of space. Other than that, well… I don't want to give too much away. But it’s not an in the round experience. It's more “semi proscenium.”

And you had some other collaborators as well, right? Can you tell me a little bit more about the collaboration on the visual design with Cao Yuxi (JAMES)?

Yeah, I'm working with JAMES as one of the visual designers of the work. I first saw his projection work at a lighting exhibition in London in 2022. I was really drawn to what he was doing and the way that it seemed like there were just these particles shifting in space, this idea of dust, which represents this transition from life to … something else. Also watching His Dark Materials. All that stuff is interesting to me; it relates to ideas of the future and change and society and religion.

The title "Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful" is evocative. How does it reflect the core message or themes you want to communicate?

I mean, it is really a prayer. It’s a prayer in all of the ways. It's a prayer for me – I do pray at night. And it's not about being connected to any one sort of religion, but just trying to put out a hope that I can continue to change and be better. I always want to be a better person. I want to believe that my parents, who have passed on, that their spirits are happy and free. But the title is about hoping that I can continue to change and be a better person and to find someone… As I get older, it's easier to feel less desirable. As a Black queer person of a certain age, it's really hard to not always feel really emotional or vulnerable – for all the reasons – but even just as it pertains to, like, queer aesthetics. I don't really know where I fit in, in a way that allows me to feel like I can meet someone who will want to be with me.

And separate from me, it’s also a conversation with nature; watching nature and the environment constantly change and shift. And part of the reality of making this work was the reality of the present day in 2021 – there is so much fear around ideas of pandemics and death and hatred. So the prayer is also for this world to be better. So it's all of those things. It's vulnerable. It's anxious. It’s fearful. It's hopeful.

It sounds like it's embodying a lot of what a lot of people are feeling right now. I'm curious, as part of your creative process in general, and specifically as it relates to this piece: do you workshop these ideas with your dancers? Or ask them to find their own experiences in the work’s themes?

In making work, generally speaking, I share with my dancers a lot of what I'm going through and what I'm experiencing. For this work in particular, I wrote my own narrative and I shared it with a couple of the dancers before I got into the studio with anyone. There are moments in the work where I've asked them to think about questions like what would they want to change about themselves? Or what are the things that they feel insecure about in their life that they would love to shift? And so there are moments where that comes into the work.

I started this work with a singular dancer, Stephanie Terasaki, who I refer to as my “movement translator.” Whenever I'm working for other companies like New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theater, Royal Ballet, Ailey, etc, she's in the room teaching the work. We first met when she was a senior at the Juilliard School, and we've worked together on several projects. When we started together working on this piece, the first day that I started making some phrases for the work, it really stemmed from conversations we were having at the time around our fears.

The work is not an AIM show, but the dancers from my company are involved as well as dancers from outside. It needed more dancers, a larger cast. This was an opportunity for me to make something in a bigger way, and to work with some new people I wanted to work with.

The idea of starting with the narrative, is that typical of your creative process?

If it's an evening length work, generally I approach it as “I want to do this thing. Let me write it out and then I'll do it.” The next works for AIM – specially I've written those narratives out, have several written for the next however many years. But if it's a shorter work that I'm making, I don't usually do that.

Do you find that your process of making a piece is different depending on the group of dancers that you're working with? For example, if you are working with your own company, is it more collaborative?

You know, I always say that collaboration isn't even about generating steps, it’s really that transfer of information one way or the other. So even if I'm making every single step, it's still a collaborative process. At A.I.M, there are several shows where I've made every single step and wrote every word that you're hearing, but I try to create it in a way that it seems like it's improvisation. Kind of like in that Faye Driscoll way. In Faye's work, people always think that things are happening in real time, but it is really meticulously choreographed in a brilliant way.

And working with new dancers – for example, the ABT work was really collaborative, but I was making every single step. I don't think people would expect me to be making those ballet steps. I think that it speaks to how much of a wonderful experience I had there, I could throw something at them and then see how they respond. I'd say to Catherine Hurlin and Joseph Markey, “Oh, I don't like this lift I made. Y'all got something better?”

Even when I'm home at A.I.M, some dancers might still want me to make every step and some dancers may not want me to make any steps. You know, I think we're in an interesting time with dance right now where a lot of dancers coming out of training programs don't actually want to do set choreography. They just wanna move.

So this is a hard question, but since you mentioned it and it's relevant to the idea behind this piece: How has your experience as a choreographer changed as you've gotten older and well not to make assumptions, but maybe you are experiencing physical limitations that you didn't when you were in your 20s?

I mean, ironically, the biggest shift is I feel like I am actually going back to my 17 or 18-year-old-self. When I got to SUNY Purchase, I'd only been dancing for a year or so. And ironically, because of that, I wasn't insecure about certain things. I was never coming from a place of ego. I just loved dance, just wanted to be dancing. Like, in ballet class there are so many things that can get in our heads, but if we just try to just enjoy dancing, that's part of the kind of the yoga of dance, right?

I try my best to not get in my head around what my body can do. I mean, that's the beauty of having Stephanie in particular, because she can do everything. And I love her so much and trust her that I don't feel insecure dancing in front of her or next to her. Well, on stage I might…

How often do you perform in your own works?

Next to never. I haven't performed for a very long time with the company, but I will still sometimes do a solo thing. I did a project with Robert Glasper a few years ago; he asked me to perform with him at the Kennedy Center with Meshell Ndegeocello. I was like, of course. Let me start stretching.

But I don't usually perform at any AIM show, maybe like a solo here or there, but never in a group piece. Those insecurities are very real. Memory, stage fright. I still have stage fright dancing a solo, but with a group of people, I'm like, next level.

Is that something that you always experienced, even when you were at Purchase?

No, I feel like it's gotten much worse. I think the higher the stakes are there and the more eyes are on me, I feel like, “Oh God, I really gotta get this together.” When I was at Purchase, the thing I always messed up was the bow. I didn't mess up the show. I messed up the bow.

Last question: What's next for you artistically? After this at the Armory, is there anything in particular you're looking forward to?

We go to our winter intensive directly after. Like, the next day we fly out to LA. We do our winter intensives at USC and our summer intensives here in New York. So, I think that's going to be good for us to get into that space, from performance right into that intensive kind of vibe.

But yeah, this work – I don't know where it's going after New York, but I don't think it's going for a minute. I don't think we'll do it in New York again. So it’s been nice to give this show its focus and love, and to really try and get people to come out to the Armory.

![IMPRESSIONS: [RE]DEFINING [SPACE] at Triskelion Arts](/images/features_large/3_Trisk_day_3_selects_by_caroline_alarcon_loor_064.png)