IMPRESSIONS: Levi Gonzalez “Hoary” at The Chocolate Factory Theater

Conceived and Directed by Levi Gonzalez

Choreographed and Performed by Rebecca Serrell Cyr, Levi Gonzalez and Kayvon Pourazar

Sound Composition and Performance by Senem Pirler

Lighting Design by Madeline Best

Costume and Design Guide jmy james kidd

Additional Music and Music Sources: “Luz de Luna” by Chavela Vargas, “A Child’s Question, August” by PJ Harvey, “The Dancer” by PJ Harvey

Hoary is Commissioned and Presented by the Chocolate Factory Theater

What is the role of place in performance? Place is of course essential, though its role is often incidental. While site-specific performance is certainly nothing new, the genre largely encompasses “alternative” performance spaces like parks, plazas, museums, galleries, and public spaces. Theaters are far less often considered for their site specificity. In fact, theater spaces are often built to promote their unspecificity: the black box, the white box, and the proscenium theater as blank slates of possibility. Artists, for their part, encounter a divide between site-specific presentations—often one-time or short term engagements—and replicable, site-unspecific presentations where performance is crafted to traverse any number of theatrical settings. These paradigms frame alternative sites as activated places and leave theaters to languish as un-places, vessels waiting to be filled and emptied by the rhythms of any given week’s load-in and load-out. The generic space and the portable performance thus become creative assets for the sustainability of both venue and artist, which in turn impacts the viewing public’s relationship to and engagement with place.

Kayvon Pourazar in "Hoary" at the Chocolate Factory; Photo: Courtesy of the Chocolate Factory

The Chocolate Factory Theater disrupts this paradigm by asserting and leaning into its alternative theatrical placeness. While the warehouse space is far from a traditional proscenium theater, it is a dedicated space designed for performance presentation, with theatrical sound, lighting, and stage equipment and modular seating arrangements in its open floor plan. Modular performances spaces are certainly growing in popularity, with multimillion dollar facilities like The Shed and the Perelman Performing Arts Center touting a range of structural possibilities and their material impacts on big-ticket productions and high-paying audiences. As an “artist-founded, artist-led and artist-focused organization,” the Chocolate Factory grounds the modular possibilities of their space in sustained, supportive relationships with artists and their creative labor. Each season, 9-10 lead artists and their collaborators benefit from dedicated multi-week, salaried creative residencies along with commissioning funds, equipment, and production support to create work by and for themselves and the space, which they can alter and rearrange to suit their purposes. Performance dates and audience capacity are at the discretion of the artists, and the Chocolate Factory offers tiered ticket pricing (“pay as much as your circumstances allow”) for all its presentations. This holistic commissioning and presenting model remains unique among New York City venues and provides a kind of place-based support structure that aims to drive artists’ creativity toward an integral sense of theatrical placeness. I’m never quite sure what to expect when I enter the Chocolate Factory; every time it looks and feels entirely different as each artist harnesses and transforms the space as a structural, aesthetic, and atmospheric agent in their work.

The artist Levi Gonzalez is no exception: his diptych “Hoary” inhabits the Chocolate Factory with a pointed attention to place that calls upon human, geological, industrial, and mythological timescales to conjure traces of material and symbolic meaning. Gonzalez and his collaborators voice these intentions explicitly through oration and storytelling, but they just as often communicate implicitly through the interweaving of movement, sound, and objects. The resulting multidimensional journey grounds us in physical place as a departure point for affective places: dark, funny, delightful, jarring, eerie, and transportive.

The work’s opening sequences for Gonzalez and Kayvon Pourazar methodically traverse the “pre-stage” spaces of the Chocolate Factory’s concrete-floored lobby, prompting the audience to engage with the performance before we even take our seats. Amid the pre-show chatter, we begin to hear a repeated call and response across the room: “Levi!” “Kayvon!” “Levi!” “Kayvon!” A space clears in the crowd as the performers approach and recede from each other, all the while modulating and mirroring the tone, volume, speed, and inflection of their calls. They quiet into an embrace and move a few steps deeper into the space, repeatedly rearranging their bodies into intimate sculptural configurations. This time they modulate posture and tenor as they brace and grapple with combative muscularity and the tenderness of surrender, colliding and breaking apart with audible effort before settling into a warm embrace of recognition.

Moving ever deeper into the space, the two pause just before the edge of the stage to disrobe and embark on an exploration of the body as place. A whispering soundscape emerges, composed of small noises that hint at enclosure, isolation, distance, and the natural world. In this charged and dreamy air the artists bind, sculpt, and knead their own quivering, undulating flesh in patient acts of recognition, effort, and care. Each ascends slowly from the floor, heels hovering on the edge of levitation, then pick up their neat piles of clothes and shoes and depart. We’re left with a lingering sense of knowing them, a sense tinged with the stain of voyeurism and the blush of empathy.

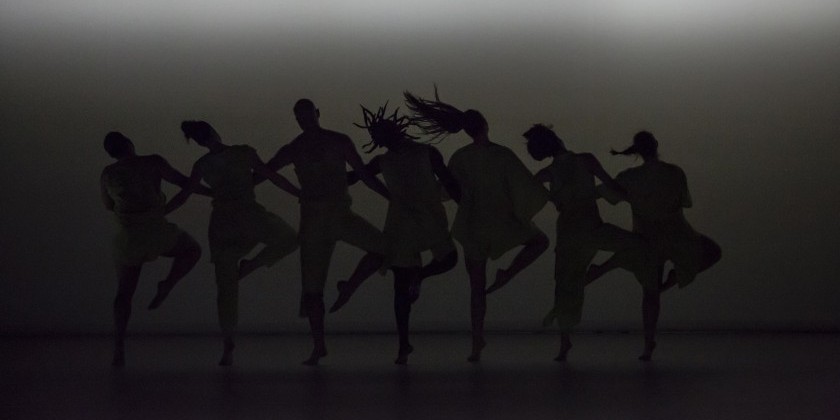

Levi Gonzalez ,Kayvon Pourazarm and Rebecca Serrell Cyr in "Hoary" at the Chocolate Factory; Photo: Courtesy of the Chocolate Factory

In the unexpected interval we take our seats around the perimeter of the stage floor and wait. And wait. Small whispers and sighs barely ripple the air; miraculously, hardly anyone has their phone out. Clustered in threes and fours facing inward from all sides of the floor, we can see one another clearly—I’m hyperconscious of my notepad—and we’re all relieved when the performers reenter, now in full costume and dramatic makeup, the duo turned trio with Rebecca Serrell Cyr. Through a relentless cascade of interlocking scenes, the artists take turns reading stories at a small table with a microphone; by way of introduction Gonzalez weaves a semi-fictional history of the Chocolate Factory’s site and structure. He colors images of the place’s almost absurdly varied history: sheep grazing at a creek’s edge, industrial masons cutting marble in a warehouse factory, artists making experimental performance for the grassroots avant garde. These histories merge into flights of imaginative lore and ghost stories that call attention to presence and absence across time and space. Structural materiality comes to the fore as the performers produce sound with objects and surfaces throughout the space. A symphony of clatters and bangs melds with their rising voices as the detritus of found objects accumulates on stage, only to be unceremoniously cleared as Gonzalez stamps out a persistent two-step and Cyr recites a litany of “once upon a time”s.

Periods of seeming chaos bring passages of formality into sharp focus. At two key points the performers join palms and reel through a rigorously rhythmic unison dance, first accompanied by the resonant clop of hard-soled heeled shoes and later by the slap of their bare soles to the driving tune of PJ Harvey’s “The Dancer.” Each time, their two-step builds in complexity, braiding through syncopations with precise control and hurtling momentum, their faces aflame with effort and joy. Rigorous questioning channels through bodies and objects across disparate registers: wordless wails and chants rub against pristine technical and gestural codes as the performers activate objects, surfaces, and each other. In a final sequence they tumble in clouds of raw wool, evoking the ghosts of grazing sheep as their bodies appear and disappear into the matted clumps like talismanic conduits to the land beneath them.

With its mythic histories and dreamlike departures, “Hoary” attends to place as an unstable entity constituted by human, animal, material, ecological, and temporal elements. The Chocolate Factory’s placeness proves to be a generative point of departure, one that opens the question of place and performance more broadly. Where will we go next?