IMPRESSIONS: New York Theatre Ballet's "Lift Lab Live"

October 30, 2020

Choreography by Victor Abreu, Richard Alston, Martha Clarke, Antonia Franceschi, Rachael Kosch, Robert La Fosse, José Limón, Marco Pelle, and James Sutton

Dancers: Alexis Branagan, Julian Donahue, Giulia Faria, Mónica Lima, guest artista Miki Orihara, and Amanda Treiber

Pianist: Alice Hargrove

Remaining Performances: 8 p.m., Nov. 6; 7 p.m., Nov. 7; 8 p.m., Nov. 12-13; and 7 p.m., Nov. 14

Tickets are $20 and must be purchased in advance. Seating is limited. Click HERE for more information

New Yorkers thirsty for culture have been parched for months. Accustomed to guzzle, we now sip cautiously from a stream of events that is nearly dry, watching incredulously as a flourishing arts scene turns to dust. The city’s vaunted intellectual life is at a standstill, along with its social life. Tyranny keeps us in a chokehold.

Some hardy groups persist in sharing their art with a live audience, however. Spunky little New York Theatre Ballet is in the midst of a remarkable “fall season” it calls Lift Lab Live, offering two alternating programs in this company’s second-floor studio at St. Mark's Church In-the-Bowery. They admit only a handful of viewers to these all-but-private showings of dance solos and the odd duet. Yet the atmosphere is soul-stirring, even with clear-plastic screens isolating audience members. Open doors and windows allow fresh air to circulate; and surely no one is more grateful for this oxygen than the masked dancers, who breathe their own exhaust while performing heroic feats. Let no one take this dedication for granted.

Following a welcome from NYTB’s intrepid director, Diana Byer, Friday’s lineup (Program B) opens with two pieces in a Romantic vein, choreographed by Robert La Fosse. Both these dances are set to excerpts from Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words; and the finishing touch on this exquisite program is Alice Hargrove’s piano accompaniment to certain pieces, resonating sensibly in the studio.

Pensive gestures and desultory wanderings characterize LaFosse’s Returning. Submerged in this solo’s wistful atmosphere, dancer Amanda Treiber seems to move reluctantly, stopping to rest by one of the studio’s pillars. Suddenly, however, she casts off her languor surging upward from a demi-plié and springing into windblown leaps. Will the rest of us ever return to freedom?

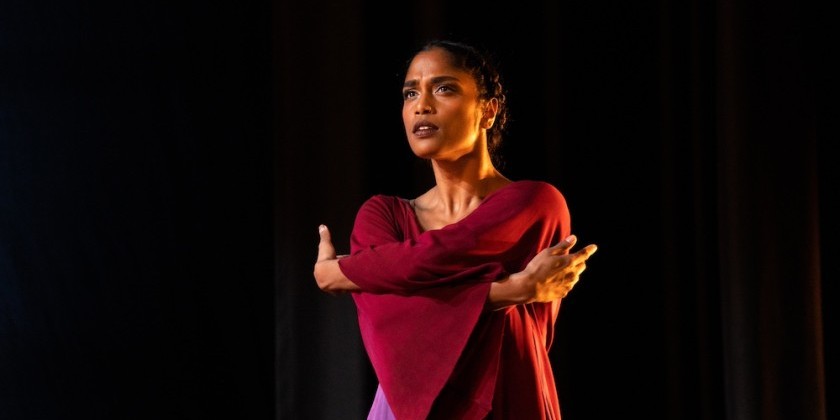

The following piece, titled Escape, has nothing tentative about it. Dancer Alexis Branagan is clearly in a hurry to depart, although even at her most excitable, her movements appear measured and elegant. Unlike the heroine of Balanchine’s Serenade, this woman does not lose consciousness when she falls, but seems abashed, as if afraid that someone has seen her.

Offering an abrupt change of pace—it’s amazing how much style fits into a 3-minute dance—the “Sphinx” solo from José Limón’s The Winged portrays a man-eater. Giulia Faria is Limón’s sleek predator, her arched fingers resting on the ground like claws, and her legs twisted beneath her. In one of this solo’s most striking images, the dancer crosses one leg over the other and leans forward perilously. Her folded body seems to conceal a secret, perhaps the answer to a riddle.

Typically intricate, Richard Alston’s Distance offers a tantalizing sample of a ballet that NYTB hopes to present in 2021. Quick and darting, yet contained, dancer Julian Donahue keeps changing direction, whipping around as if unwilling to commit to any course that would draw him out of his rugged self-absorption.

Choreographer Jean Volpe’s Speranza returns us to a world of aspiration and triumphant attainment. Rising on pointe, Mónica Lima’s lines are finely chiseled. She lifts her feet deftly in prancing steps; and her speed confounds as she performs a series of chaîné turns. Ballet has its own technology, but one that reminds us of our potential without de-humanizing us. Lima bids us farewell touching her hand to her heart.

Martha Clarke’s Nocturne is this program’s nod to Halloween, a number in which Miki Orihara plays a moldering Sylphide risen from the grave. Wearing a long Romantic skirt, but topless, her head is shrouded in a bag of tulle. She drags herself along painfully, clutching her bosoms with a crabbed arm and fussing with her costume. Perhaps this revenant is trying to recapture, or at least remember, former glories.

Treiber returns transformed into a robotic character in Rachael Kosch’s Three Things. With her hands flattened, she performs a faceted dance changing position to display the colored panels of her costume; then she revolves in attitude giving us a 360-degree view as she promenades. The solo unexpectedly shrinks when it zooms in on Treiber’s fingers and toes, which go on the march like columns of ants.

At a live event, even solo dancers rarely seem to be alone. The audience is a silent partner, more or less acknowledged. Yet choreography enters a new dimension when dancers share the stage, which partly explains why Antonia Franceschi’s Topogo (In One Spot) is so satisfying. Franceschi peppers this duet with ersatz folk motifs, following her Bartók score. More significantly, the choreographer manages to borrow the music’s smoldering atmosphere, so while watching a neo-classical pas de deux (with entrechats!), we feel the tug of a relationship that is part competition and part seduction. Mónica Lima and Julian Donohue are Franceschi’s Romanian firebrands.

A good ballet class is more than simply a dry repetition of exercises. It teaches the student to seize the moment, and to perform with éclat, as choreographer James Sutton reminds us in Gavotte Fantastique. Neatly symmetrical and flowing, with intricate steps that pave the way for space-devouring moves, this gracious “classroom” solo proves to be a star vehicle for Alexis Branagan. Lovely!

Inspiration is sadly lacking from Victor Abreu’s A Moment in Time, but three minutes of boredom seem like a small sacrifice on a program featuring 11 works. The next piece, Marco Pelle’s L’Uno di Due, quickly atones for the lapse.

Amanda Treiber is the expressive soloist, who begins upstage with semaphoric gestures, initiating a sequence that later we will see repeated front-to-back. Though she advances straight down the center, cutting a furrow with sharp relevés on pointe, Treiber’s busy hands and shifting torso give this dance a mysterious, dodgy quality. The floor-plan is simple, but the dancer as elusive as lightning. When she takes off at a run, fingers fluttering, we can calculate her circular trajectory without ever hoping to capture her.

New York Theatre Ballet will continue to perform live through November 14, a small company steadfastly defending our humanity with a handful of programs. For those who truly love the arts, it will be a pleasure to attend.