IMPRESSIONS: Isabelle Huppert in "MARY SAID WHAT SHE SAID," Directed by Robert Wilson

Direction, Set, and Lighting Design: Robert Wilson

Starring: Isabelle Huppert

Text by: Darryl Pinckney | Music: Ludovico Einaudi | Costumes: Jacques Reynaud

Associate Director: Charles Chemin | Associate Set Design: Annick Lavallée Benny | Associate Lighting Design: Xavier Baron | Associate Costume Design: Pascale Paume | Collaboration for Movement: Fani Sarantari | Sound Design: Nick Sagar | Make Up Design: Sylvie Cailler | Hair Design: Jocelyne Milazzo

Translation from English: Fabrice Scott

A Production of Théâtre de la Ville-Paris with support from Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels.

Venue: NYU Skirball Center

Dates: February 27 - March 2, 2025

“I am the raging of women’s madness,” says Mary Stuart, and listening to her deliver a feverish monologue in Mary Said What She Said, a play about Mary Queen of Scots, we take her at her word.

In a redoubtable performance by French actress Isabelle Huppert, the tragic queen posthumously defends her reputation, her mouth agitated as she recalls episodes from her tumultuous life. Thanks to director Robert Wilson, the mastermind of this exquisite production, which made its US debut at the NYU Skirball Center on February 27th 2025, Huppert’s scarlet mouth becomes a character in its own right, desperate to testify before its breath runs out. This amazing soliloquy, in French with English supertitles, comes to us from the Théâtre de la Ville, in Paris, where it debuted in 2019, and the performances receive support from Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels.

Isabelle Huppert in "MARY SAID WHAT SHE SAID." Photo: Lucie Jansch

As a royal celebrity, Mary Queen of Scots has much to recommend her to audiences that relish the misfortunes of the rich and famous. A pawn in affairs of state, persecuted by powerful enemies, and with a susceptible heart, Mary cannot enjoy her life of privilege but must pay for it by placing her head on the executioner’s block. This is the stuff of historical romance; and one can easily imagine the story luridly upholstered in a Hollywood pageant. The wonder is that Mary not only survives transplanted to the Minimalist world of Robert Wilson, but that compressed by a severe style her passions seem to redouble and she demands our sympathy.

In this airy production built out of light, with incidental music by Ludovico Einaudi, and text by Darryl Pinckney, Huppert freezes or moves mechanically, while the non-linear plot advances in fits and starts. She speaks to us directly or in voice-overs, further fragmenting the narrative. Repeating certain passages from the text, Mary reveals her obsessions while the words drill into our heads. She recalls the companions of her childhood, four maids-of-honor all named Mary, and Diane de Poitiers, the royal mistress who taught her life’s graces. Marriage to the Dauphin made her the Queen of France---briefly, as the timid youth died a year later. She tells us she did not know that thousands of her Scottish subjects perished for the sake of this alliance, victims of an English invasion. She would learn many brutal facts.

Mary’s pride in her royal accoutrements — the jewels, the processions, the tapestries — alternates with horror, as she recalls witnessing a shipwreck, the burning of witches, and the murder of Catholics in Scotland. She marries a second time, and a third, falling in love and longing for the comfort of her husband’s shoulder, but accusations of murder haunt her; and she is separated from her child. She suffers a bloody miscarriage, and is imprisoned in sunless, moldy rooms. Even her beloved pets suffer cruelly. Hanging over all is a vision of the scaffold draped in black, where in her final moments she bared her neck to the axe; and her realization that Death, “the hooded figure in the throng, is always a surprise.”

Though this narrative abounds in detail, Wilson sets it in an amorphous, environment where Huppert’s figure in an antique dress resembles a cut-out, silhouetted against a backdrop in pearly tones, or solid teal. Later, Wilson will go for more striking effects, bathing Huppert in a blue light that pools in her shoulder-blades, or turning her face bright green as she opens her mouth to screech silently. In another segment, she sits amid fluffy clouds holding a golden, bird-like object in her hand. The only other props are a white dancing shoe that enters mysteriously on a track, and a blank envelope that disappears down a hole.

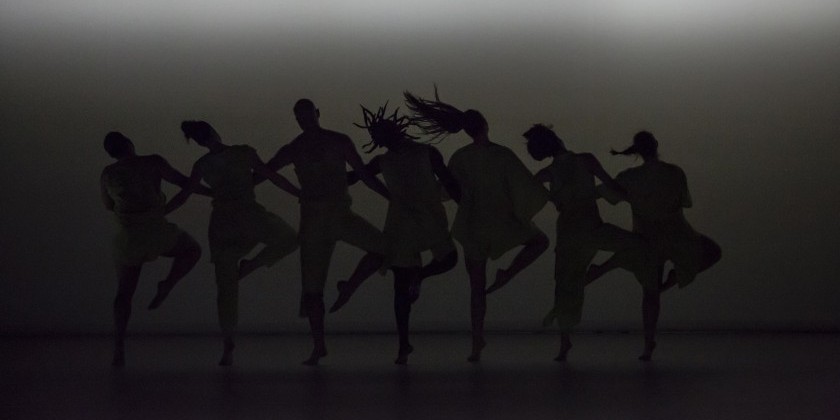

Though initially motionless, with her hands resting flatly before her, Huppert’s rusted limbs gradually come alive. She extends her arms to the side for balance, as if dancing a Pavane; and her hands curl ornamentally. She may tilt suddenly, or execute a glacial turn. She bobbles as she moves around the stage, and throwing her arms up she travels back and forth repetitively along a diagonal path. At one point, she reaches forward as she walks, as if fearing to encounter hidden obstacles. Toward the end, she seems to confront herself in a mirror dance, doubled by Fani Sarantari. Occasionally, Wilson allows Huppert to “act,” pursing her lips with pleasure or wrinkling her face with distaste. All these movements seem isolated, and gain power from their independence. Yet Huppert manages to make us feel we are watching, and listening to, a real woman, however much she may be the victim of protocols antique and modern.

What a pleasure to experience Robert Wilson again. Seamless and austere, Mary Said What She Said reveals a heroic vision rare today.