IMPRESSIONS: American Ballet Theatre in Cathy Marston’s “Jane Eyre”

June 5, 2019 at 7:30 p.m.

Choreography and Direction: Cathy Marston

Scenario: Cathy Marston and Patrick Kinmonth

Compiled and Composed Music: Philip Feeney

Set and Costume: Patrick Kinmonth // Lighting: Brad Fields

It may be one of the most famous lines in English literature. Appearing near the end of Charlotte Brontë’s beloved bildungsroman, the titular Jane Eyre declares, “Reader, I married him.” These four words chime climactically for the “friendless orphan” who finds love while staying true to herself.

Like the great story ballets, Jane Eyre draws heavily from fairytales. It mixes the rags-to-riches of Cinderella with a bellicose beast of a lover who’s tamed by Jane’s inner beauty. A touch of Bluebeard materializes in a mad wife who’s been hidden in the attic, so her husband can take a new bride. All the drama transpires with shadows licking at the edges of both the morally claustrophobic Victorian era and Jane’s roiling conscience.

What sets Jane Eyre apart, then and now, is its confessional first-person point-of-view. You, the reader, have entry to Jane’s thoughts and feelings — even the carnal ones. She holds nothing back, and this access to another’s head and heart, scandalous at the time of publication, is riveting.

Translating this complex interiority to the theater’s third-person perspective is a challenging task. Choreographer Cathy Marston, who’s made a name for herself by bringing the literary canon to the stage, was tapped to create Jane Eyre for Northern Ballet in 2016. When a program fell through, American Ballet Theatre added the two-hour work as part of its Women’s Movement. How much you enjoy the ballet may reflect your relationship to the novel — and to Jane herself.

Patrick Kinmonth’s elegant set conjures the book’s gothic gloom. With scribbles and streaks careening across their dark fabric, curtains and scrims tighten the Metropolitan Opera stage to a more intimate environment. Depending on how the light hits, they suggest everything from the blackboards of Lowood (a Dickensian boarding school) to the bleak moors that Jane roams after discovering Mr. Rochester, her employer and paramour, is already married.

Spare arrangements of seating relate power to position. The schoolgirls of Lowood perch on stools, the seat of which lifts to produce a desk. At Thornfield Hall, where Jane works as a governess, an imposing chair for Mr. Rochester rests stage right. After his wife burns down the manor, leaving him blind and broken-spirited, all that remains of the chair is a burned-out metal skeleton.

If only the other elements conspired to be as haunting. Philip Feeney’s score pulls from Schubert and both Mendelssohns yet never extends beyond bland symphonic swells. Unlike the best dance music, whose melodies burrow deep inside you, this barely registers.

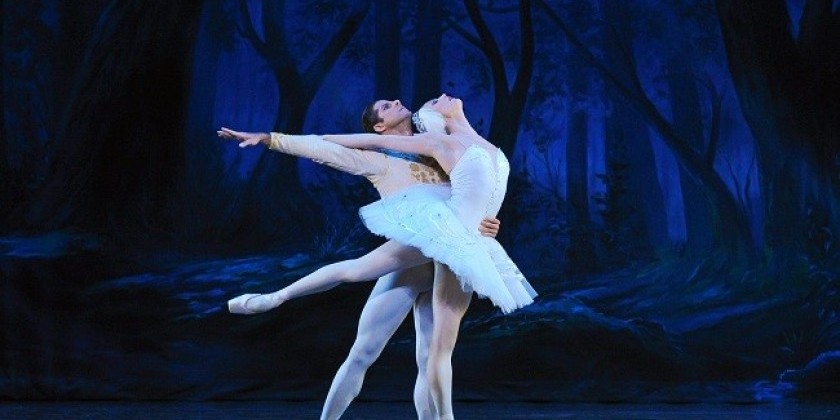

Marston’s choreography is equally undistinguished. Moments — the tick-tock precision of Lowood’s students as they sup and study, a posh bash of waltzing gentlepeople — do resonate. Yet they’re swept up in an endless eddy of swirling movements that all look the same. The many pas de deux between Jane and Mr. Rochester fail to capture the lovers’ ardor (too much clutching at and whirling around each other), and their “bantering” is depicted through the extension of a pointed foot at a 45° angle. Although the intent may be to indicate a sharp, candid wit, the effect is vulgar, like they want to trip someone.

In dance, a mediocre vision can be saved, even elevated, by its performers. I fear the cast I saw (there were three) demonstrated unfamiliarity with the source material. As Jane, Isabella Boylston looks the part more than she acts it, emphasizing technical flash over reeling emotion. This is better than Thomas Forster (Mr. Rochester) who performs as if he’s in an entirely different ballet. Though tall, he moves small, seldom manifesting the outsized snarl and passion of one of literature’s most romantic leads.

.png)

While many of the secondary roles last a handful of minutes, some performers imbue them with nuance and sensitivity. Playing Mr. Rochester’s deranged wife, Cassandra Trenary uses the Mary Wigman-esque gesticulations to hint at a troubled spirit worthy of our sympathy. Hee Seo appears all too briefly as the kittenish socialite Blanche Ingram; the way she inclines her head says more than any fancy phrase could. Duncan Lyle takes the zealous missionary St. John Rivers who wants to marry Jane for practical reasons and infuses him with grace.

Whether you appreciate these portrayals may depend on your ability to follow the plot, which Marston refuses to compress. With seventeen named characters, eleven scenes, and two Janes (Skylar Brandt plays Jane as a young girl), and one in media res opening, befuddlement seems inevitable. I itched to take a red pen and excise all the needless exposition because what Jane Eyre needs is more and better attention to the inner lives of its protagonists.

Jane, in particular, gets a raw deal. Instead of unpacking the heroine’s rich psychology through her actions, Marston employs a male corps called the D-Men (the D is for demons and death). The men dash around her, throw her to the floor, and hoist her skyward. Often, Jane stands motionless as they billow about, like dancing footmen in a Disney movie.

According to the program notes, the Greek chorus represents the men who block Jane’s way and rob her of agency. This is a reductive reading of the text where women are an equal hindrance. Jane’s aunt dumps her at an orphanage and later, out of malice, declines to tell Jane about a wealthy relative who wishes to adopt her. Most important, Jane must get out of her own way, let her desires duke it out with her morals. That’s why she’s a heroine for the ages, and it’s what’s missing here.

ABT's Spring Season continues through July 6, 2019. For more information and tickets, please visit HERE.