Impressions of “Daniil Simkin's Intensio”

Producers and Presenters: The Joyce Theater Foundation, Joyce Theater Productions and Sunny Artist Management Inc. with Daniil Simkin, Ilter Ibrahimof and Courtney Ozaki Moch

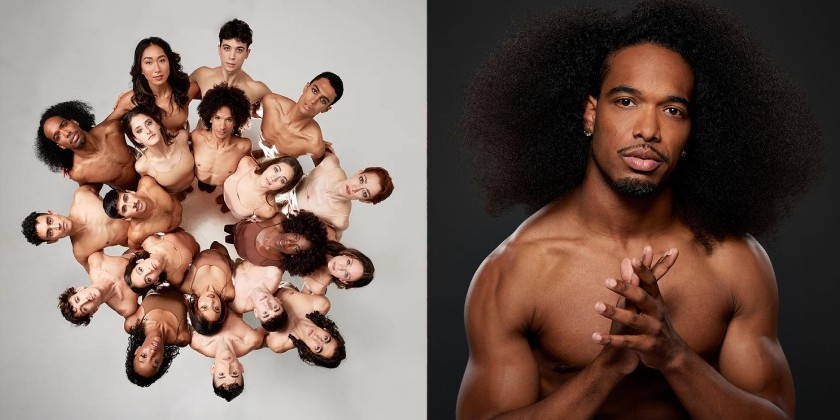

Dancers: Daniil Simkin, Isabella Boylston, Alexandre Hammoudi, Blaine Hoven, Calvin Royal III, Hee Seo, Cassandra Trenary, James Whiteside and special guest Céline Cassone

Co-Commissioner: Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival / Lighting Design: Nicole Pearce

Production Manager: Steven Carlino / Company Manager: Barbara Frum

Costume Coordinator: Maile Okamura / Costume Design for “Islands of Memories”: Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung

Musician: David Friend

The ballet world’s latest celebrity showcase, Daniil Simkin’s Intensio, sounds like a cardio-fitness workshop. Despite its promise to set hearts pounding, though, none of the new dances that Simkin, an American Ballet Theatre principal, has commissioned for this pick-up company has much of an impact.

The culprits, er, choreographers include Alexander Ekman, Jorma Elo and Annabelle López Ochoa, plus young, American dance maker Gregory Dolbashian. At the center of this program, which opened on Tuesday at the Joyce Theater, comes Ekman’s short film Simkin and the City paired with the same choreographer’s dance-theater piece Simkin and the Stage. These quirky items help remind us who the evening’s star is supposed to be.

Simkin and the City gently needles our host for his obsession with ballet. It shows him waking up already dressed in his prince’s costume and eager to begin a new day filled with pirouettes and leaps. He practices on his way to work, dancing down the sidewalks and into the subway, arriving at the Metropolitan Opera House only to find the door locked. Though the film is a gag, the incredulous stares tourists give the ballet dancer as he sweeps past (New Yorkers don’t bother to look up), and his encounter with the locked door, supply more insight than perhaps we ought to have into this artist’s odd-ball personality.

In the biographical Simkin and the Stage, however, we learn still more about him. After a nugget of dance history attempts to trace the current program back to the 17th century, Simkin recalls his childhood. His Russian-émigré parents were both dancers, who home-schooled him in ballet from a tender age working to produce a virtuoso in a small, family apartment that in no way resembled Versailles. Thinking ahead they filmed some of the classes, giving Ekman a stock of archival images to use as a backdrop. The story, as Ekman tells it, is supposed to have the ring of destiny, with Louis XIV ganging up with Simkin’s parents and browbeating the child until he renounces his interest in dentistry and agrees to follow the path to stardom.

This plan has a couple of holes in it, however, the first being that there is more to stardom than having ambitious parents and a crackerjack technique. A genuine star has a face and a personality that shine with their own light, sparking with electricity and casting everyone around them into shadow. And while Simkin is highly skilled, he does not possess that luminosity and glamor. In fact, when Intensio casts him alongside some of his pals from ABT — including Isabella Boylston, Blaine Hoven, Calvin Royal III, Cassandra Trenary and James Whiteside — Simkin is easy to overlook. For all his suave pirouetting, he does not tower above the others making Intensio an awkward attempt at self-promotion.

The other problem involves ballet’s five positions. As Ekman’s history lesson reminds us, Louis XIV’s ballet master, Pierre Beachamps, went to some trouble to codify them, but, alas, the elaborate syllabus that evolved after 1700 does not inspire the contemporary choreographers of Intensio. Even when these dancemakers condescend to use ballet vocabulary, they don’t love the steps enough to focus on them, polish them and show them off with pride. There’s always something more important that requires attention, like a digital light show or the impulse to squirm. So why did Louis XIV do all those pliés? And what was the point of making a child in a threadbare apartment in Wiesbaden repeat these exercises nearly 300 years later?

Elo has sketched a triangle for his Nocturne/Étude/Prelude, with Boylston as a romantic weathervane swiveling first toward Simkin and then toward Whiteside. Like all the dances on this program, Elo’s is well crafted. Boylston begins upstage center facing us, and ends in the same place with her back to us, with many neatly arranged figures coming in between to satisfy a desire for symmetry and order. The choreographer also holds his piece together with movement themes, like the flat-palm gesture that Boylston uses to push Simkin away when she no longer wants him. That gesture turns ironic, when she tries to use it later to prevent a disenchanted Whiteside from abandoning her.

Orderliness is no substitute for imagination, however, and Elo’s squiggles, crouches and slides are all predictable, not to mention sharply at odds with Chopin’s lyrical Étude Op. 25 (the “Aeolian Harp”), played live by pianist David Friend. Furthermore, in a piece with an imbedded narrative, Elo has made little effort to define his characters. Only Whiteside stands out in a solo that brands him as the emotional one, with Boylston and Simkin both coldly on the make.

Dolbashian’s Welcome a Stranger has a looser, rangier style with five dancers sliding into position and freezing, or slithering across the floor. The action often takes place low to the ground. Combined with a shadowy lighting plot and with a vague mix of music and sounds that inexplicably halts and then picks up again, this under-the-radar movement gives the dance a cautionary atmosphere as if something illicit were going on. Dolbashian’s weasely characters aren’t shy about grabbing or even kicking one another, and hands laid firmly on a person’s shoulders have the same coercive implications as a recurring head-lock. Configurations keep changing, and the dancers all have solos, but we remain in the same, mysterious netherworld until the end, when Céline Cassone, a go-for-broke artist from Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal, falls into the arms of someone waiting in the wings.

López Ochoa may be best known in these parts for the delightful pieces she has choreographed or restaged for Ballet Hispanico — including flamboyant Mad’moiselle, witty Sombrerísimo and the powerfully sensual Nube Blanco. Her new work for Simkin’s company, titled Islands of Memories, displays the same love of theatrical showmanship, but falls short because Ochoa, like so many contemporary artists, appears to have a limited acquaintance with or interest in the ballet lexicon and its possibilities.

The piece expands in an orderly manner, with figures composed of duos and then trios. The opening image shows Simkin lying on his back stretched on a digital beach where wavelets have carved the sand into strands of light. Near the end the piece contracts again, focusing on a duet for Simkin and the increasingly exhausted Cassone. Then the choreographer leaves Simkin more or less where she found him, a lonely castaway dreaming of the bustle he knew in another life. If only those dreams were more vivid!

López Ochoa tries to create a sense of urgency by rushing entrances or staging tense stand-offs where the group pauses to stare at someone who has ventured out on her own. Apart from that final, entropic duet, however, the choreographer does not develop her pas de deux into intriguing personal encounters. Locked together with the woman folding or unfolding against the man, a couple simply revolves around itself trapped in a relationship like a whirlpool.

Islands of Memories would be entirely forgettable, if it weren’t for the set and visual design supplied by Dmitrij Simkin — the lead dancer’s father. Mirrors hang overhead, fragmenting the action and offering different perspectives. Most dramatically, figures move in pools of light layered in bright colors, as if the dancers themselves were islands surrounded by shoals of varying depth. These designs resemble and may actually be heat maps. Where the heat comes from in this tepid program is anybody’s guess.

Share Your Audience Review. Your Words Are Valuable to Dance.

Are you going to see this show, or have you seen it? Share "your" review here on The Dance Enthusiast. Your words are valuable. They help artists, educate audiences, and support the dance field in general. There is no need to be a professional critic. Just click through to our Audience Review Section and you will have the option to write free-form, or answer our helpful Enthusiast Review Questionnaire, or if you feel creative, even write a haiku review. So join the conversation.