IMPRESSIONS: WOMEN IN MOTION 2019/2020 — Pop Performance Opportunity Project at Gibney

January 30, 2020

Women in Motion Directors: Melissa Riker, Erin Cairns Cella, and Amber Sloan

Featuring Rebecca Stenn, asubtout (Katy Pyle +Eleanor Hullihan), Same As Sister (S.A.S.)/Briana Brown-Tipley + Hilary Brown-Istrefi

The producers of the Women in Motion series are deadly serious about supporting female artists, but that doesn’t mean they present boring dances. Far from it. The latest installment in their program, Thursday night in The Theater at Gibney, featured a trio of works that were alternately touching, playful, and rambunctious.

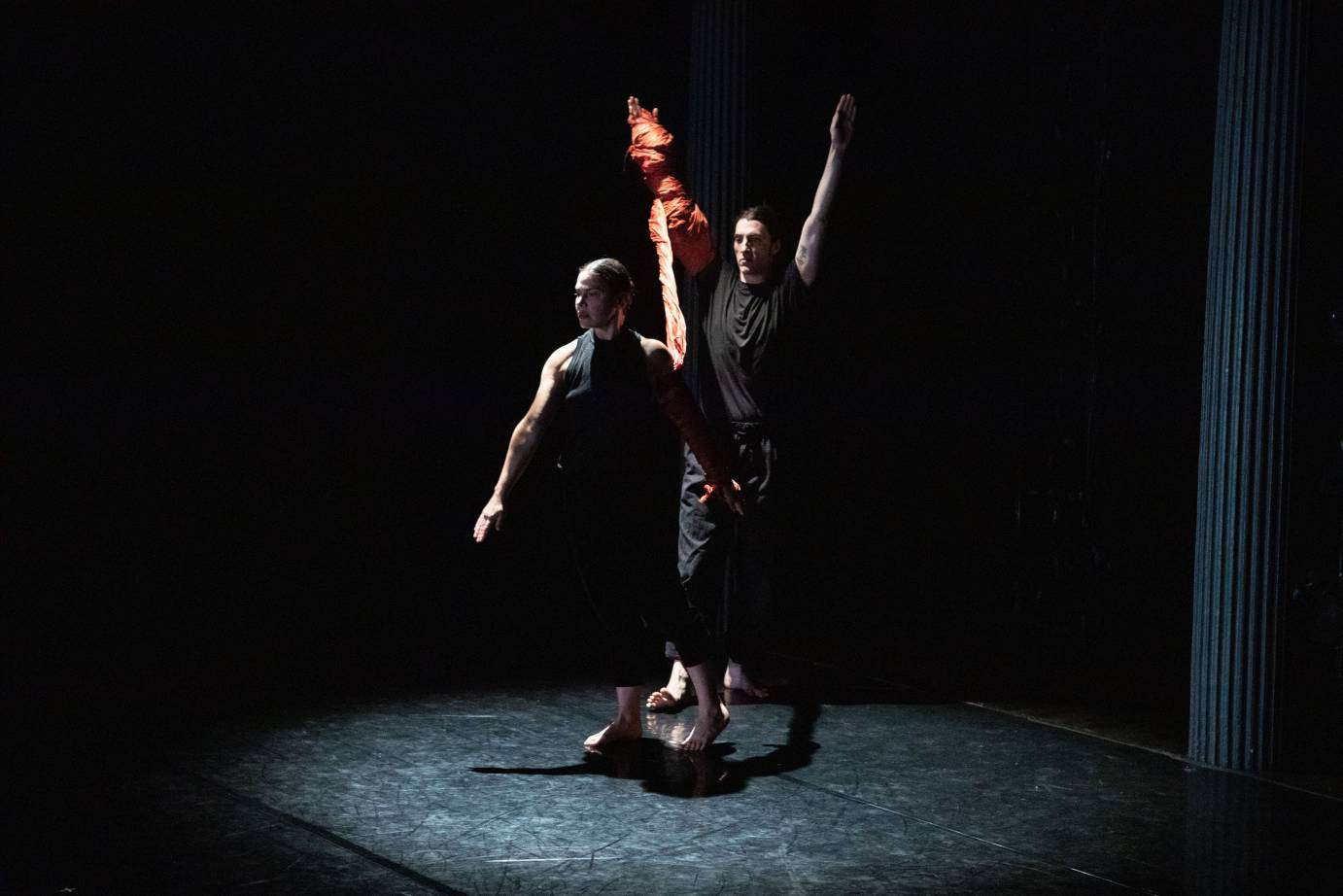

Choreographer Rebecca Stenn is all tied up at the start of her piece, The Oak and the Willow, a duet that she performs with Quinn Dixon. A length of orange fabric winds around their arms binding them together. During the first part of the dance, set to the lonely blast of fog horns and the splash of ocean waves, the two performers are occupied with disentangling themselves: Stenn peels away first, and then hovers over Quinn as he works to free his arm from its orange wrapping.

Later sections, set to the murmur of Jay Weissman’s electric bass, involve a pile of clothing and dry leaves. The dancers try on winter coats; and at the very end, after Stenn has abandoned the scene, Quinn rifles through the pile tossing garments into the air. Is he maddened by her departure, or searching for something left behind?

The best parts of The Oak and the Willow have nothing to do with props, however. I love the moment when Stenn and Quinn hold their arms up stiffly and their hands begin to soften. Focusing our attention, their flat palms curl deliberately and then the hands begin to soar and dip like sea-birds. More than the slow and steady passages in this dance, or the bursts of speed, I also love the parts when the movement freezes abruptly and the energy of twisting gestures seems held in suspension. At such moments, Stenn and Quinn appear truly free—not just conscious, but living with intent.

The Centaur Show, a 2007 duet that creators Eleanor Hullihan and Katy Pyle have revived for this occasion, takes its cue from campy, science-fiction fantasy of the Barbarella type. Wearing horse costumes, with tails and shaggy leggings, they prance in unison and perform a dance of interlocking symmetries that leaves them hot and panting. Picking up microphones, Hullihan and Pyle explain that they are centaurs who have been expelled from their home in a distant star system (presumably Alpha Centauri). Although the message of these interplanetary visitors remains obscure, they earn laughter with a tongue-in-cheek song about crystals, in which a love object turns out to be counterfeit—not crystal at all, but merely a lump of soap. The choreography itself is crystalline, tightly organized with sharp, mirrored surfaces, although it culminates in a circle with the two dancers rolling and flipping as they orbit around a central point of gravity.

Kallax, a work-in-progress by the art collective known as Same as Sister, is more in-our-faces. A burlesque routine is the centerpiece, but as soloist Leigh Atwell gyrates and squeezes her ass cheeks for our benefit her shadow falls on the backdrop where we see a video of people shopping at Ikea. There are itches, and then there are itches; and maybe it doesn’t matter whether the stuff we mindlessly consume is sex, or food, or furniture. Should we suppress our urges, or simply be more conscious of the way that advertising stimulates us?

Kallax doesn’t offer an alternative to consumer porn, just variations on the theme of horniness within a Nordic setting. Ah, those long, dark nights. Jamie Robinson appears as an underwear model, displaying his product repetitively as we hear the scratch of an old LP going ‘round and ‘round. Nearby Leigh Atwood stands on a giant ice cube writhing and moaning. Briana Brown-Tipley and Hilary Brown-Istrefi are a pair of masked twins, child-like but still restless and unable to keep their mittened hands to themselves.

There’s a lot of writhing as Kallax heads towards its conclusion, in which Hay is forced to flee through a snowstorm; fire engines arrive with sirens blaring; and bewildered shoppers must evacuate the Ikea store with their purchases half completed. If only Same as Sister could take full credit for this Götterdämmerung farcically re-imagined as consumerismus interruptus. But if they had set the fire themselves, they would be in jail.

Maybe the audience for the next show at Gibney will wonder why the floor is sticky. If so, they can blame it on Same as Sister and their Swedish meatballs.