IMPRESSIONS: PAGEANT Presents "Cavity" by Amelia Heintzelman with Dorothy Carlos

Choreography & Performance: Amelia Heintzelman

Musical Composition & Performance: Dorothy Carlos

Set: Val Karuskevich

Lighting: Shana Crawford

Dramaturgy: Sophia Parker

Costume: Ayano Elson

Dates: December 5 and 6, 2024

PAGEANT is something of an East Williamsburg treehouse, looming three stories above Graham Avenue. One enters through an unassuming door — at night, nestled between metal storefront security gates — and climbs two flights of stairs before arriving in an impossibly deep loft that spans the length of the building. After attending performances at PAGEANT, I know better than to anticipate the configuration of the space. The wood-floored and white-walled room is fluid.

I always look up before going inside because the street-facing floor-to-ceiling windows glow with invitation.

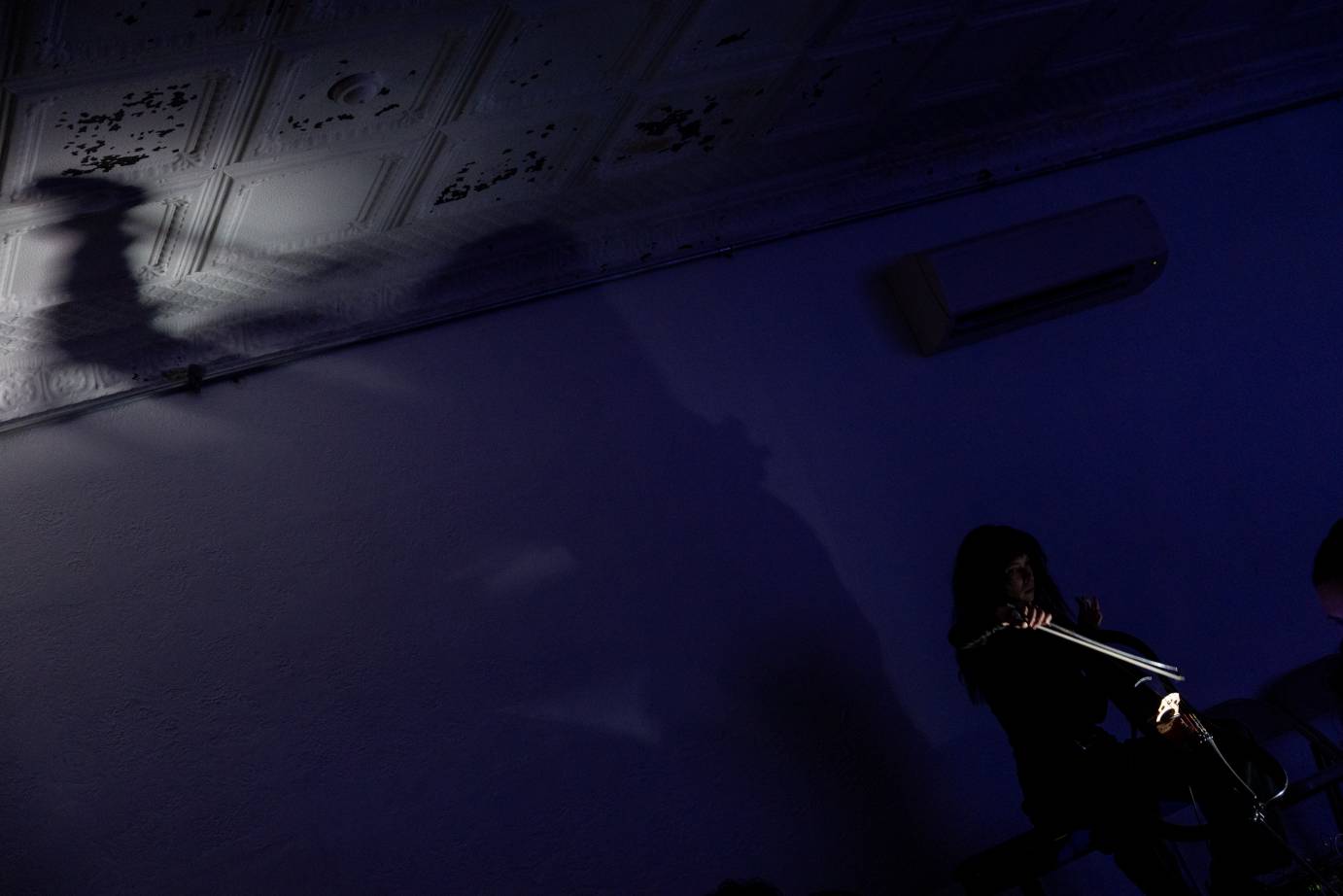

For Cavity by Amelia Heintzelman with experimental cellist and electronic musician Dorothy Carlos, the performance area was a square of reflective black floor contained on two sides by black velvet risers. Carlos’s cello rested in the middle of one riser section, its bridge illuminated. A single footlight bathed the corner between the windows—usually obscured by a beige curtain, but left exposed this time — and the wall in a cool hue.

Carlos entered first, settling herself and the cello. She drew her first sounds by rubbing her fingers up and down along the strings. She scraped the riser with the cello’s endpin and peered over in an apparent attempt at excavation. Sometimes, a pluck escaped, but mostly it sounded like squelching or wet burrowing. Obviously, I thought, the sound was amplified for performance. But it felt particularly intimate, like it was very small and far away. I understood I would not have been able to hear it without a technological, non-human aid.

Heintzelman entered quickly, stood with one heel raised, and scanned the audience in defiant acquiescence to the circumstance of being watched. She bent her knees and rested her hands on them in a position that alluded to athletic readiness, or catching one's breath. Except her heels were raised, so the shape was precariously balanced. Finally, she lowered into a squat, pelvis open to the single footlight.

Heintzelman began a score of stomping and pivoting. Each pivot was catalyzed by her elbow or ribcage. Her hands were active. Throughout this score of frantic yet deliberate torsion her gaze alternated between the audience, the wall, a distant, dancerly “out,” and, most curiously, down. When Heintzelman looked down, I noted a glimpse of introspection or softness towards herself. The score was punctuated by an eerie grinning scream from Heintzelman, matching Carlos’s tone.

Carlos tracked Heintzelman diligently with her eyes. Her sounds seemed to drive Heintzelman’s pathways, yet Heintzelman sometimes contradicted them in speed and tone. Dramaturg Sophia Parker writes for Culturebot, “When I look at [Carlos]’s hands as they stroke, slide, pinch her cello’s strings I wonder if she is the conductor or conduit of this turbulent landscape.” I wondered the same and leaned toward conduit. Heintzelman never reciprocated Carlos’s watchful gaze.

I was made uncomfortable by the fact that I could not place Heintzelman’s degree of autonomy. She folded into idiosyncratic and distorted shapes with meticulous calm — more resolute than enthusiastic. When she crouched, bowed her head, and reached through her legs to hold her pelvis, her hands looked disembodied. Logically, my mind could not entirely separate her hands from her body, so instead I held the tension between truth and perception.

From her strange (but not awkward) crouch, Heintzelman crossed her legs at the knees in a tight spiral as if wringing out her body like a towel. Carlos produced a penetrating ringing sound, and then a melancholic, repetitive progression. It was finite and exhausted. Heintzelman gently and gradually released the shape and crumbled to the floor. She lay, and then pushed herself backwards towards the corner between the wall and windows. Once she arrived she positioned herself upright, legs splayed in line with the right angle. She was weary. Her body surrendered to the architectural limitations of the space, yielding for a moment at the farthest point from either riser packed with observers.

Carlos’s squelching sounds returned and reminded me of the suction tool at the dentist. Heintzelman rose unceremoniously and was drawn to the windows. She stood close to the glass with the restraint of a particularly well-behaved (or terrified) child at the aquarium, caution and curiosity suspended midair. I watched her blurry reflection hovering above the street garland on Graham Avenue as she made tiny side steps from the left corner to the right. She was very close to the outside but not desperate to go there. Perhaps she resigned to the impossibility—the deceitful transparency of the glass.

Cavity is a work in response to Heintzelman’s emergency surgery for a ruptured ovarian cyst some years ago. I was drawn to her description: “a violence inside my body invisible to everyone except my surgeon.” I experienced her and Carlos’s performance with questions about inhabitance and authority. Performers cultivate the interior of PAGEANT to suit their visions, but it is always still PAGEANT, all white and brown and beige, all East Williamsburg commercial building. Even when covered the windows invite curiosity to pedestrians below, but the happenings themselves are obscured by distance and walls. For women and all people assigned-female-at-birth, the health and science of our reproductive systems are comparably obscured by medical institutions and bureaucracies. How much do we know about our interiorities—and how they manifest externally — beyond how they feel? Is that ever enough?

When Heintzelman completed her survey of the windows, she turned, walked to the center of the space, sat, opened her legs in another right angle, and looked at her reflection in the floor. Her gaze was conscious — internal and far away. The lights clicked off.