IMPRESSIONS: Cunningham on Film (Part 2): "MERCE / MISHA / MORE" and "Event at REDCAT"

"MERCE / MISHA / MORE_A FILM EVENT" and "Event at REDCAT"

Featuring: Mikhail Baryshnikov, Merce Cunningham, Jacquelin Harris, Chalvar Monteiro, and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

Venue: Baryshnikov Arts Center

Director: Daniel Madoff | Producer: Nancy Dalva

Featuring: Mikhail Baryshnikov and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

Producer: Mighty Egg Productions | Presenter: Baryshnikov Arts

Choreographer: Merce Cunningham

Additional credits: Click here

See also: Cunningham on Film (Part 1): "August Pace 1989 - 2019"

This year Baryshnikov Arts celebrates the 50th anniversary of Mikhail Baryshnikov’s arrival in the West, a momentous occasion for the global dance community that continues to resonate through his ongoing contributions to the field as an artist and leader.

This year also marks the 60th anniversary of Merce Cunningham’s first “event” performance, and this happy confluence culminates in a program that features the two artists in conversation through dance. Billed as a “film event,” the program takes on the patchwork-style structure of Cunningham’s site-specific “events” that stitched together bits of choreography to suit a particular space or theme. In this case, the event centers on the relationship between Cunningham and Baryshnikov, who danced a handful of Merce’s own roles and remains an avid supporter of his work.

MERCE / MISHA / MORE delivers just what the title indicates: an intimate look into Cunningham’s process, Baryshnikov’s interpretation of the work, and an expansive meditation on time, change, and context for the dance and its dancers.

Director Daniel Madoff with Mikhail Baryshnikov and producer Nancy Dalva. Photo: Maria Baranova

Baryshnikov, of course, is best known as a ballet dancer and one of the most prominent figures in dance to emerge in the 20th century. He is, however, far more than a virtuoso star who upped the ante on ballet’s technical and expressive potential. He is an eminently curious artist who draws on an exhaustive well of naturalistic physicality to engage and explore within and beyond his vernacular forms. The rigors of Cunningham’s technique and choreography are in many ways quite suited to ballet dancers: the surface-level grammar of their formal structures, shapes, and kinesthetic dynamics fall within a similar range. And while Merce avoided using ballet terminology to refer to movements, opting instead for directionally descriptive cues, it can be hard not to see an arabesque for an arabesque in his work.

But in other ways, Cunningham’s work diverges as its own ballet-derived modern dance dialect, one with an expanded range of unexpected, sometimes disjointed syntactic possibilities for the limbs and spine. Its mode of expression is not driven by narrative, character, or music, yet is thoroughly and nakedly human in its approach to physical rhythm, athletic impossibility, and tactile subtlety at wildly telescoping scales. As a ballet dancer, my own attraction to Cunningham’s work is rooted in these very qualities, which made Baryshnikov’s perspective and interpretation of the work all the more illuminating.

Both Baryshnikov and Cunningham’s voices and bodies are equally revealing as the film sketches their portraits through snippets of interviews and studio footage. Cunningham’s minimal yet assured directional commands drive the rigorously exploratory tone of a 1967 rehearsal, and his voice and intent carry through the several decades traversed in the film. Baryshnikov speaks of his attraction to the “internal drama” and “confused familiarity” of the work and his embodied experience of the deconstruction, segmentation, and rearrangement of physical logics. As dancers, the two are entirely different animals both structurally and instinctually: Merce’s long, lanky angularity and startlingly erect percussive sensitivity contrasts with Misha’s compact, prowling strength and finely shaped virtuosic nonchalance.

When the two artists come together in the studio, they assume an intensity of focus in which rigorous physical repetition supplants the need for words. A 1994 rehearsal for Signals (1970) highlights their shared focus and mutual respect: faced with a challenge, the choreographer offers little more than the trusting space of silence for the dancer to figure and refigure intricate passages. 1999’s Occasion Piece showcases the two artists side-by-side: 90-year-old Merce leans on set pieces to support his minimal yet alertly purposeful dancing while 51-year-old Misha glides through the choreographer’s own roles before his eyes. Echoes reverberate through the elder’s body as a matter of simple fact, not nostalgia, as the dance channels into a new body to become a new fact.

About midway through its thematic statement, the film takes an odd (yet gorgeous) digression to present a lengthy excerpt of 1972’s Landrover, danced by Jacquelin Harris and Chalvar Monteiro, two current stars of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Filmed in Baryshnikov Arts Center’s airy sixth-floor Merce Cunningham & John Cage Studio, its inclusion highlights Baryshnikov’s ongoing support of Cunningham’s work from off stage.

Harris and Monteiro are classical dancers of prodigious talent and presence—I posit Harris as one of the greatest dancers of this century — and the tense thread of their duet yields a visceral pleasure that brings to life the purity and mystery that so attracted Baryshnikov to Cunningham’s work. Landrover is a work that undoubtedly merits further presentation, perhaps even as part of the Ailey company’s (as of late rather uneven) repertory.

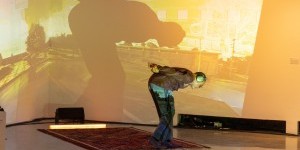

A short jump from this meandering meditation lands us in an exploration of a singular rehearsal and performance process for "Event at REDCAT", a 2010 presentation by the Cunningham company that featured Baryshnikov as a guest artist. The film, directed by former Cunningham company dancer Daniel Madoff, eschews much verbal exposition in favor of letting the dance speak for itself, from the varied bustle and focus of the rehearsal studio to the glowing liveness of performance. Baryshnikov remains at the center, but the Cunningham company dancers are by no means peripheral — they are integral to seeing Baryshnikov’s dancing amid the landscape of their bodies (a “mosaic,” as he envisions it in the previous film). Their presence also illuminates the evolution of Cunningham’s work as it formed around new palettes and technologies in the changing bodies and capacities of the dancers.

Baryshnikov’s physical idiosyncrasies in the work have the play of an exotic accent in a foreign tongue as Cunningham’s steps channel through his balletically-engraved neural pathways. The tells are subtle, perhaps noticeable and expressible only to a discerning eye and empathetic body: the vestiges of a regal carriage of the torso, the graceful shapes and facets of hands and fingers, a quiet yet uncontainable flamboyance loosely shaken off. These are some of the very same tells that reveal my own balletic vernacular tendencies in Cunningham’s work, ones that I initially struggled to overcome or mask and have now come to incorporate as a flexible foundation for an iterative exploration of technical range and possibility. As an undisputed master, Baryshnikov commits himself equally to the movement’s motivation and its shining result, contrasting looseness and stillness in passages of stylistic dabbling in mannerism, rhythm, and form. At 62 — an age at which Merce was still actively performing with his company — the ease and clarity of Baryshnikov’s solos are meant to contrast with the stunningly complex athletic feats performed by the company’s agile dancers.

The performance space fills and clear in waves: dancers tag team in and out of a whirling stream of tessellated trios; a double duet unfolds with fast and slow phrases like passing ships; Baryshnikov cuts through with lithe triplets and a bouncing gait, his arms a busy tangle above. Throughout, the cast’s assured grammar of physical segmentation sacrifices neither dynamic nor momentum as one movement fires the next in a kinetic chain reaction. They proceed to toss large pillows around the stage, tumbling into what would appear to be a mass chaos were it not for their impeccable timing. They wrap it up with a neat button, scrambling into a cluster with Baryshnikov at the center, posed for a family photo.

Just before the credits rolled for the evening, Baryshnikov had one last surprise up his sleeve: one final, brief dance with Merce. A clip from Charles Atlas’s 1999 Just Dancing shows the choreographer, supporting himself on a portable ballet barre, grooving to an uptempo dance beat. His characteristic geometric directionality and signature physical quirks transcend his aged body for a moment of sheer joy. Baryshnikov appears in the flesh before us, watching for a beat before he joins in the shuffle. A handful of dancers (myself included!) pop up from our seats, and for a minute there we are, three generations sharing a boogie on stage and screen. It’s a small but significant gesture to express the completion of a circle: what Merce made possible for Misha, Misha now makes possible for me, for us, and ultimately once again for Merce.