IMPRESSIONS: Bebe Miller Company in “Vespers, Reimagined (2025)” at Danspace Project

Original Choreography & Performance: Bebe Miller

Original Music: Linda Gibbs

Collaborating Performers: Bria Bacon, Jasmine Hearn, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Chloe London, Stacy Matthew Spence; K.J. Holmes, vocalist; Hearn Gadbois, musician

Choreographic Consultant: Angie Hauser // Creative Consultant: Niall Jones // Project Manager: Lila Hurwitz

March 28, 2025

Thulani Davis’s “Poem Untitled, 1982” punctuates Danspace Project’s 2012 “Parallels” Platform catalogue in six short, rhythmic sections:

Working in new

forms, stepping

outside tradition is

like taking a solo…

The artist breathes

in a heap of air, the

chords, tones, and

even the structure of

his or her world and…

And then in one

concentrated

moment moves

and breathes

out…

The sound becomes

a shape, a dance, a

configuration of what

we know that we have

not seen or heard that

way…

The black artist

makes this happen

out of the most rigid

traditions, in a society

where our crafts are

often not honored…

…but still with

that sensibility that

taught the world how

to solo—solitary

yet communal,

disciplined and free.

These words are a dance in themselves, signposting as evocative interludes between essays, photos, and ephemera from the original 1982 “Parallels” program (for which the unpartitioned poem served as epigraph) and its 30th anniversary corollary in 2012, both curated by Ishmael Houston-Jones. In his curatorial essay for the 2012 Platform catalogue, Houston-Jones details how his intention in 1982 centered on Black choreographers creating outside the mainstream “in parallel worlds of Black America and new dance.”

Thirty years later, shifts in social contexts and artistic definitions guided him and co-curator Will Rawls toward an ethos that could “keep looking forward, while remaining cognizant of our shared pasts” to propose a destabilized and multifaceted “new black subjectivity in dance.” This commitment and Davis’s words resonate through time with embodied assertion and lasting presence, still an apt adage for Black artists today.

The poem also succinctly captures the spirit of Bebe Miller’s “Vespers,” which premiered in the 1982 “Parallels” program and returns for a 2025 reimagining as part of Danspace Project’s 50th anniversary season. Miller contributed to the 2012 “Parallels” program as well, and takes the current celebration as yet another occasion for reflection and evolution, coming home to the very floor where she made her breakout turn. She reflects in a program note: “Returning to ‘Vespers’ now with these artists has been a kind of archeological dig into how we’ve all arrived at our various understandings of the art, the currencies, as well as the physics of dancing.”

“Vespers” (1982) is a jewel of a work: a luminous 14-minute structured improvisation for Miller and vocalist Linda Gibbs. Upon its premiere, Deborah Jowitt hailed Miller in The New York Times as “one of the rare ones who makes dancing seem the most profound thing in the world.” Her profundity is at once steely and delicate, forthright yet never overly self-serious as she launches and spools her lithe, youthful frame into scribbles, spirals, and finely-etched figures. Hers is a whole body composed of discrete parts, indelibly connected and tenaciously independent. Tension gathers in her hands, never held, and releases into space, never aimless; her restless spine, electric even in stillness, is just as Davis describes: “disciplined and free.”

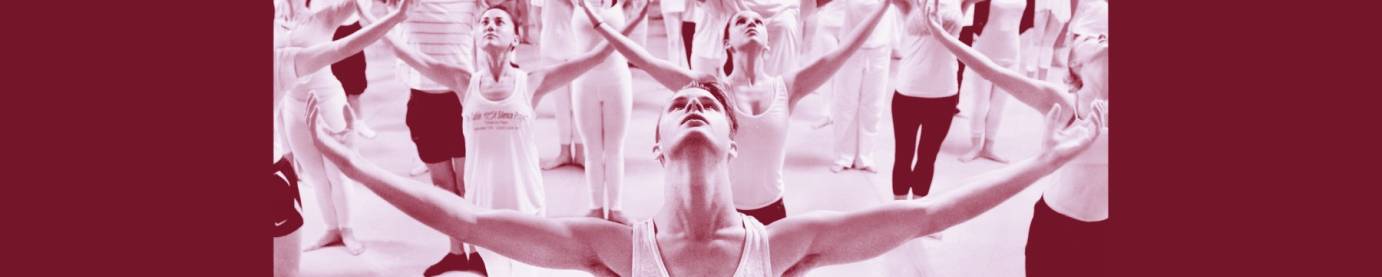

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to imagine replicating — or “reviving,” as if from death — a dance so connected to an individual artist and her time and place. So for “Vespers, Reimagined (2025),” Miller expands the original work into a 40-minute dance-essay for five sensitive, daring dancers: Bria Bacon, Jasmine Hearn, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Chloe London, and Stacy Matthew Spence. They move in constant conversation with Miller, whose presence lingers in overlapping projections of looped clips from the original video; she also appears on stage, moving and speaking both alone and among the group.

K.J. Holmes lends resonant vocals in multiple arrangements: layered over Gibbs’s original score, a cappella, and accompanied by live percussion by Hearn Gadbois. Gibbs’s soaring, wordless tones evoke Gregorian chants — sacred music floating through a sacred space — with which Holmes converses in meandering phrases of rounded vowel sounds, her cadence one of poetry or prayer. Later in the work, Gadbois intercedes with complex, interlocking rhythms on an array of percussive instruments; perched on the steps of the altar, the movements of his playing echo in the dynamics and details of the dance: fluttering fingers, trembling hands, feet at once solid and nimble. As in the original, interludes of silence foreground the musical structures of moving bodies propelled through the vibrating air.

The audience watches from the carpeted risers along either side of the church’s sanctuary; we are thus positioned to look through the dance’s action as the video runs in our visual periphery. This arrangement allows for a spatial enactment of dance historical processes: the referent flickers as the current unfolds, and we see each other as co-constitutive of the work’s present history. Miller assists directly in this work, addressing us in her customarily warm, open manner with reminiscences and reflections on the passage of time in her body, her work, and her community. She dances with the very same signatures as her young shadow on the wall, her movements deepened and burnished with time.

Many choreographers working in contemporary dance use their own improvisations as the basis for co-constructions of set choreography for other dancers; this does not strike me as Miller’s project in reimagining “Vespers” with her group. While their improvisations respond to Miller’s original phrase work — sometimes directly, at others tangentially — they are wholly their own: jubilantly alive and unapologetically individual. Solos, pairings, lineups, and simultaneities abound in the shifting stage space, animated by alternately frank and moody lighting that serves to focus or reveal the movement and its environment, including us. Unisons sharpen and break apart, fleeting moments of contact fuel the dancers’ collective engine with risks, rebounds, and supports. In one moment, a giggle erupts from a tangle and the dancers whisk themselves offstage as Miller enters through them; they anoint her with their passage.

Miller injects humor into the proceedings as she faces off with the dancers while wielding a laptop playing the 1982 video. With this brief game, she pokes at the absurdity of replicating, or even approximating, her improvisations. The dancers must instead make their own choices, informed by their movement instincts and lineages and the idiosyncrasies of their bodies and personalities: Bacon’s voracious precision, Hearn’s supple playfulness, Jenkins’s expansive grounding, London’s mischievous curiosity, Spence’s quiet athleticism. Miller — in both 1982 and 2025 — contains shades of all these qualities, and still the dancers exuberantly exceed the parts of her sum.

Bodies scatter and collide for exercises and interventions in co-improvisation, consolidating periodically to traverse the space together in a wavering line. Toward the work’s closing, strong light hits them from the front and above, casting long shadows behind them as they walk forward in slow motion. They advance independently with quick weight shifts and suspended follow-throughs as their shadows overlap and intertwine in their wake, a living elegy. Miller closes with a dedication to the artists swirling in her historical and current milieus, intoning with calm assurance: “This is our now.”