IMPRESSIONS: Martha Graham Dance Company's "American Legacies" Season at New York City Center (Part 2)

Rodeo

Choreography by Agnes de Mille // Music by Aaron Copland // Bluegrass Arrangement by Gabe Witcher // Stage Design by Beowulf Boritt // Costume Design by Oana Botez // Lighting Design by Yi-Chung Chen // Staged by Diana Gonzalez; Tap Solo Choreography by Dirk Lumbard

The Gabe Witcher Sextet: Gabriel Witcher, Fiddle; Bryan Sutton, Guitar; Paul Viapiano, Mandolin; Wes Corbett, Banjo; Isaiah Gage, Cello; Paul Kowert, Bass

We the People

Choreography by Jamar Roberts // Music by Rhiannon Giddens // Arranged by Gabe Witcher // Costume Design by Karen Young // Lighting Design by Yi-Chung Chen

Appalachian Spring

Choreography and Costumes by Martha Graham // Music by Aaron Copland // Set by Isamu Noguchi // Original Lighting by Jean Rosenthal, Adapted by Beverly Emmons

Satyric Festival Song

Choreography and Costume by Martha Graham // Reconstructed by Diane Grey and Janet Eilber // Music by Fernando Palacios

Maple Leaf Rag

Choreography by Martha Graham // Music by Scott Joplin // Costumes by Calvin Klein // Lighting by David Finley

Choreographer Agnes de Mille (1905 - 1993) was Martha Graham’s contemporary, but an artist of a different stripe. Cautious and conventional, she rebelled as far as she dared, but never managed to escape the anti-intellectualism of Hollywood, or overcome her yearning for commercial success. During the 1940s, however, both de Mille and Graham were paired with composer Aaron Copland, creating dances on American themes as part of a patriotic movement to develop a national culture. De Mille got there first, choreographing Rodeo in 1942; but when Graham’s Appalachian Spring appeared in a modernist setting two years later, her sensitive and profound treatment of a rural wedding immediately outclassed de Mille’s Western slapstick.

Martha Graham Dance Company in Agnes de Mille's Rodeo. Photo: Carla Lopez of Luque Photography

Though unflattering to de Mille, it seems logical for the Martha Graham Dance Company to combine these works now, in its New York City Center season titled “American Legacies.” As if suspecting that Rodeo lacks the backbone to stand tall amid the Graham repertoire, they have given the piece a florid makeover. Just as The Champion Roper spits on his hands to slick down the Cowgirl’s hair and brush the dust from her pants, costume designer Oana Botez has rushed in with bright calicos and chintzes for the womenfolk, and embroidered denims for the cowpokes; while Beowulf Boritt projects ranch scenery on the backdrop. Like the digital enhancements to The Rite of Spring, these projections seem designed to reassure a generation of theatergoers weaned on CGI. Even Copland’s score has been refurbished. Gabe Witcher’s bluegrass arrangement has a folksy twang, amplification compensating for its lack of orchestral heft.

The piece is still de Mille’s Rodeo, however, which is to say a mix of choreographic wiles, cornball humor, and barbs aimed at the female sex. As an example of de Mille’s dance-making skill, we can cite the neat triangulation in which two observers with different points of view catch sight of the Head Wrangler making love to the Ranch Owner’s Daughter. One of the daughter’s friends flicks her hands and smirks maliciously at the sight, while upstage the Cowgirl deflates in lovelorn despair. De Mille manages the full ensemble just as easily; and groups intersect and divide offering dramatic revelations.

Martha Graham Dance Company in Agnes de Mille's Rodeo. Photo: Carla Lopez / Luque Photography

The humor of the ballet, meanwhile, centers around the Cowgirl, whose masculine attire and whose desire to accompany the men de Mille dismisses as symptoms of romantic incompetence. Because a woman wearing pants isn’t funny — not even in de Mille’s day — the choreographer supplies her protagonist with an imaginary horse that suffers from restless-leg syndrome and an aversion to gunfire. Bucking and running off with her, this nag causes a panic; but clearly, the Cowgirl’s trespass onto male territory is the real disruptor.

De Mille isn’t satisfied, however, with lampooning the Cowgirl, who slaps the Head Wrangler’s stomach in jest while secretly longing for him to embrace her. Pulling out her knitting needles, the choreographer pursues with equal verve the women who do conform to gender stereotypes. One hypocrite strikes a pin-up pose, but is horrified when her date interprets this tease as an invitation to grab her. Another exposes her ankle shamelessly inviting pursuit; and, framed by a pause in the hoe-down, the pin-up girl returns exhibiting a ladylike tendency to vomit. Among the women, only the Rancher’s Daughter sails above criticism, secure in her lyricism and wealth. Naturally, no one dreams of laughing at the men. Why not?

The Martha Graham dancers are wonderful dramatic artists, who make the most of de Mille’s arch characters. Laurel Dalley Smith turns the Cowgirl into a pathetic waif, while Marzia Memoli’s Cowgirl is a frustrated tomboy. Alessio Crognale-Roberts portrays the Head Wrangler as a wind-burned stoic, tough as rawhide. If this character could speak, you know he would say, “Go ahead, make my day.” Lloyd Knight brings studied details to his part, walking with a crick that suggests he has spent hours in the saddle. In contrast to the Head Wrangler’s reserve, the Champion Roper is an enthusiastic skirt-chaser and a show-off. Richard Villaverde and Jacob Larsen both turn up the charm — but pity the ingenue who expects this windvane to remain constant. As the Ranch Owner’s Daughter, majestic Leslie Andrea Williams accepts the Head Wrangler’s attentions as her due; while So Young An flirts deviously. Even with such delicious performances, however, Rodeo suffers from de Mille’s constitutional inability to take risks. As a satire of Western mores, it is less amusing than the farting-around-the-campfire scene in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles. As a satire of a woman struggling with traditional gender roles, it is less wicked than the sodomy scene in Lina Wertmüller’s Swept Away.

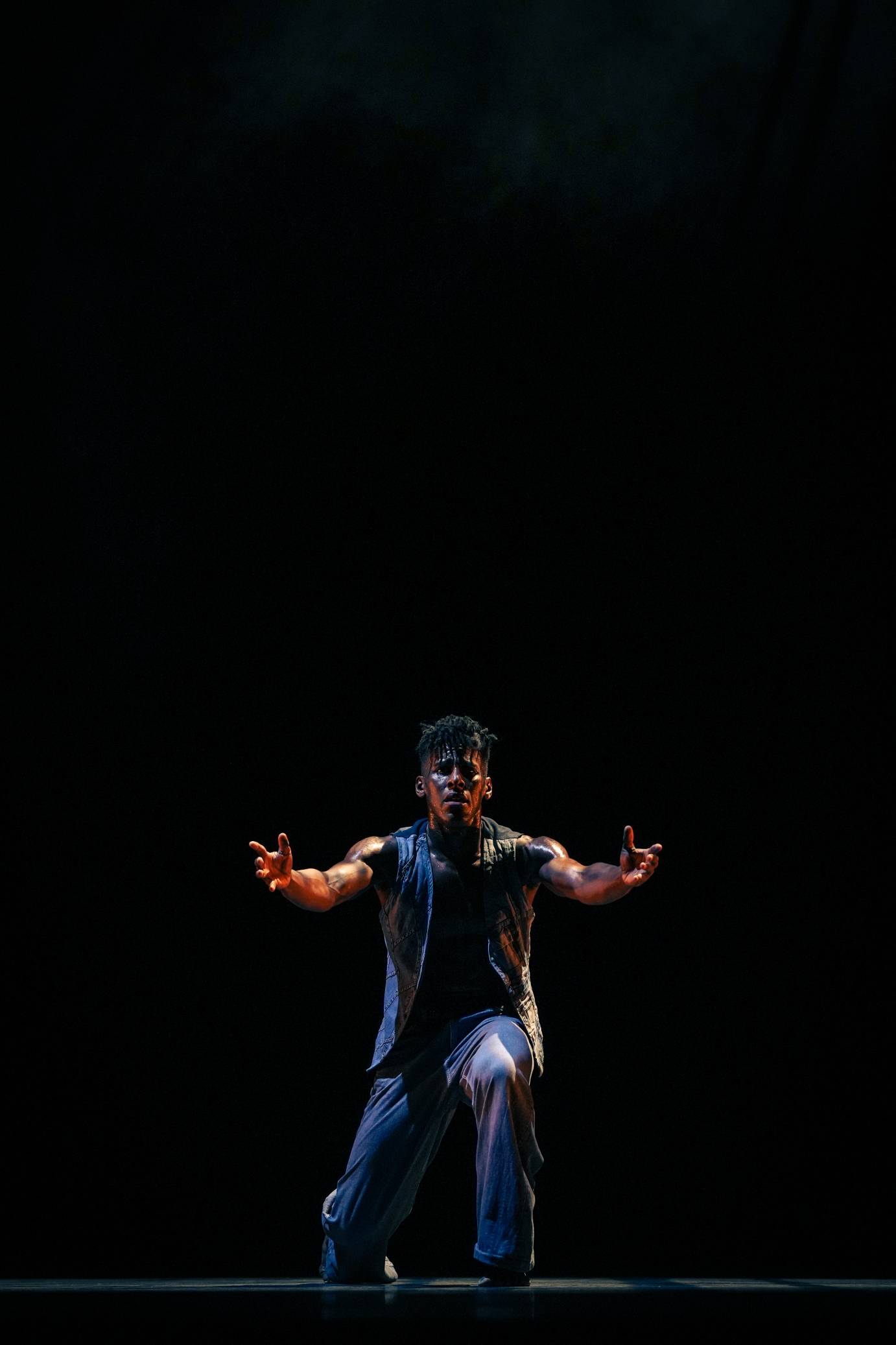

Extending the “American Legacies” theme, choreographer Jamar Roberts distills a history of struggle and resistance in his dance We the People. Neatly crafted, this plotless season premiere features a denim-clad ensemble of average folks divided into trios and triple lines, while a friendly gestural duet for Jacob Larsen and Meagan King expands into a dialog between two groups. In place of dramatic vignettes, We the People offers a string of breakout solos.

Leslie Andrea Williams sets a tone of defiance as the piece opens, her body alternately tense and yielding. She turns a shoulder warily toward us, making herself a smaller target. Sinking slowly as if someone were forcing her down, she rises again and feigns nonchalance. Alessio Crognale-Roberts faces us coolly with his thumbs tucked in (shades of Rodeo), but his confidence wanes as he begins to weave twisting side to side as if trying to avoid unpleasantness. He half-conceals his face behind a flexed bicep, but then softens as his hand turns outward. At the outset of his cameo, Lloyd Knight walks into an invisible obstacle that forces him to retreat, and everything that follows comes in reaction. Recalling Alvin Ailey’s Revelations, Knight struggles to maintain his balance close to the ground, as powerful forces twist and overthrow him. In We the People, living is a martial art. A smoky haze hangs over the stage, adding visual drama; and the bouncy folk score by Rhiannon Giddens gives way to stretches of silence that frame the soloists. Presumably Roberts felt constrained by the rhythm. Those silences haunt the piece, adding isolation and a yearning for freedom to its themes.

How different is the atmosphere in Appalachian Spring! If We the People feels distrustful and world-weary, Graham buoys her portrait of rural life with innocent optimism. This happy tone reflected Graham’s personal hopes in 1944, and her nostalgic loyalty to the generations that had tamed the wilderness. Graham was close enough in time to the epic journey of pioneers pushing Westward to understand that a life of toil and privations awaited her Bride and Husbandman in their half-finished home (try heating this Noguchi set in winter). Yet Graham chose to record the settlers’ dreams rather than their hardships. Conveniently, a vision of Americans in proud possession of their land also offered young people of the 1940s a reason to fight in the World War.

The only threat to the Bride and Husbandman’s happiness comes during the Preacher’s tormented solo. Hand trembling as if evoking the thunder of divine wrath, the Preacher chokes and accuses; while his bonneted acolytes group themselves around a recumbent figure suggesting a wake. Yet the Preacher is not the only authority in this community. The Pioneering Woman seems to embody an older religious tradition, which worshipped fertility. Having already blessed the young couple, and having knelt to caress and delve into the earth, the Pioneering Woman returns to dispel the confusion that follows the revivalist’s outburst. Indicating the horizon, she reminds the Husbandman of his dreams. Her stolid, womanly figure offers a foil both to the Preacher’s fluttery admirers, and to the inexperienced Bride, whose mood vacillates between giddiness and fear. Where a lesser artist might have given us a simple romance, in Appalachian Spring Graham embodies aspects of our history, including “manifest destiny,” and the evolution of brimstone Calvinism into Emerson’s cult of God in nature.

The Graham company now fields an ideal cast in this masterwork. Anne Souder makes a sprightly Bride. She fans her shoulders excitedly and flings herself into a scissoring leap, reaching for an invisible prize. A callow Husbandman, Jacob Larsen slaps himself in delight at the prospect before him, and hastens to celebrate hooking arms with the Bride in a round so energetic they almost levitate. Alessio Crognale-Roberts is the Preacher, stern yet erratic, who falls into the arms of his flock so they support his rapture. Leslie Andrea Williams brings lush expansiveness to the role of the Pioneering Woman.

Graham wasn’t always so profound, yet even her comic pieces betray sophistication. The capricious soloist of Satyric Festival Song scampers, hops, and fans her behind, but she also strikes zig-zag poses that anchor the piece in a modern aesthetic. Even her flying hair becomes a design element. Guest artist FKA twigs lacks the muscular tension of a Graham dancer, but has a stirring, winsome quality that makes the solo her own.

At the age of 96, Graham surprised her fans with the antics of Maple Leaf Rag, but perhaps she found a source of mirth in her own longevity. A survivor, she had laid to rest her fears and could laugh death in the face. Maple Leaf Rag isn’t a mindless romp, however, or even purely a satire. Graham plays an intricate game of contrasts in the final work she would complete.

Jacob Larsen, Anne Souder and Richard Villaverde in Martha Graham’s Maple Leaf Rag. Photo: Isabella Pagano

Ominous chords, recalling the thump of Tiresias’ staff in Night Journey, seem to foretell approaching doom, as Leslie Andrea Williams swirls across the stage in a white gown, lifting her skirt to form a circle. Like the transit of the moon, she seems to measure the passing seasons. Yet while time remains implacable, the chords surrender to the ticklish melodies of Scott Joplin, revealing a sublunary world that is a patchwork of light and shade. Here tragic figures with tense bodies and claw-like hands will alternate with insouciant couples who waltz and frisk, performing a variety of lifts and newly invented ballroom steps.

Occupying center stage, a South Carolina joggling board is a sober-looking bench whose hardness deceives. Unexpectedly it bounces and swings offering seated lovers an excuse to hold tight. The board becomes a toy for dancers to squat on, prop themselves against, and vault over. A principal couple dressed in yellow are its chief occupants, however. Full of mischief, Lloyd Knight clambers stealthily underneath the board so he can peek beneath Xin Ying’s skirt. She responds with mock offense, but a tap on the shoulder restores him to her good graces. When they try to rest, reclining on the board, a friend rouses them with slaps on the rump. Later, this same man (Alessio Crognale-Roberts) will receive a kick to his own backside. The alternate cast of principals, Richard Villaverde and Laurel Dalley Smith, are similarly lusty and coy.

Though actively intriguing, the principal couple are also spectators observing the bustle around them, prefiguring a moment when several couples perch on the board to watch and applaud a play within the play — a ferocious psychodrama, naturally. Graham is poking fun at herself, but she is also commenting on her circumstances. Old age has made her a spectator, too, not entirely sidelined but too frail to storm and swoon. From her raised vantage-point, she can see the whole of human experience, the comic and the tragic, and she notes with amusement the rascality of youth. Graham knew us better than we know ourselves.