IMPRESSIONS: In Conversation with Merce with Choreography by Merce Cunningham, Kyle Abraham, and Liz Gerring, Presented by Baryshnikov Arts Center

Choreography by Kyle Abraham, Merce Cunningham, and Liz Gerring

Music by John King and Anaïs Maviel (15/2), and by Michael Schumacher

Landrover staged by Jamie Scott // Costumes by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung

Dancers: Mariah Anton, Cemiyon Barber, Jaquelin Harris, Claude “CJ” Johnson, Chalvar Monteiro, and Donovan Reed

Watch it online, September 21-30, 2021, HERE

Choreographer Merce Cunningham died in 2009, but like all truly great artists, he continues to hold conversations with the living. It helps, of course, when an institution like the Baryshnikov Arts Center facilitates the discussion, co-producing a terrific program like the current one titled In Conversation with Merce.

Introduced by Patricia Lent, a former Cunningham dancer associated with The Merce Cunningham Trust, this online event features three duets of remarkable beauty. It opens with excerpts from Cunningham’s Landrover, a limpid masterpiece from 1972, which was revived specifically to generate creative responses from contemporary dancemakers Kyle Abraham and Liz Gerring. These artists share their thoughts with us, and then we see their works performed in the studio. Gerring has created Dialogue to a score by Michael Schumacher, while Abraham’s MotorRover is performed in silence. BAC commissioned both these pieces (thank you!).

As a choreographic model, a more inspiring, and more daunting piece than Landrover could not be found. Cunningham himself had learned from example, but rather than parrot the style of Martha Graham or Antony Tudor he was able to digest these influences completely and respond to them in a highly personal language of his own. So, while certain images in Landrover are recognizably balletic or modern, the work as a whole displays fantastic originality, reshaping its source material with a subtlety and power that are breathtaking. Cunningham attained a mastery over his material that gave him the freedom to play.

Among this work’s delights is the way Cunningham selects thematic material from odd bits and pieces. A casual, downward glance and the turnout of a knee, movements that might be considered incidental, acquire prominence here through repetition becoming piquant elements in a formal composition. Typically, Landrover is full of surprises, with abrupt dynamic changes and dancers leaping suddenly, without preparation, in unexpected directions.

Although the dance is plotless, it does not lack for drama. Interpreters Jacquelin Harris and Chalvar Monteiro display a godlike self-possession, yet when Harris suddenly dives and straightens in the middle of a pirouette, and when both dancers soar above the stage, their virtuosity is thrilling. Their relationship is also provocative, especially in those delicate moments when these partners are almost, but not quite touching.

In her interview, Liz Gerring says she became fascinated by Cunningham at an early age, attracted by his distillation of movement and by the way his dancers maintain their independence even while engaging with each another. While her own work is rooted in the “pure dance” aesthetic, it possesses a characteristic boldness and an eagerness that are both refreshing.

Dialogue opens with a striking contrast between horizontal and vertical figures: Mariah Anton lies parallel to the floor, supporting herself on her hands and moving sideways by flipping over, while Cemiyon Barber strides in calmly. Gerring staggers her dancers’ movements (keeping them independent), and she reverses the usual partnering arrangement with the woman eventually coming in close behind the man, although she doesn’t support or manipulate him. As in Landrover, this proximity creates a feeling of tension that later vanishes without ever being resolved. Dialogue has a typical sense of urgency and challenge, with additional contrasts between running and stillness, and with precarious backbends, stretches, and sudden falls. We never see the dance end, as the screen simply goes black.

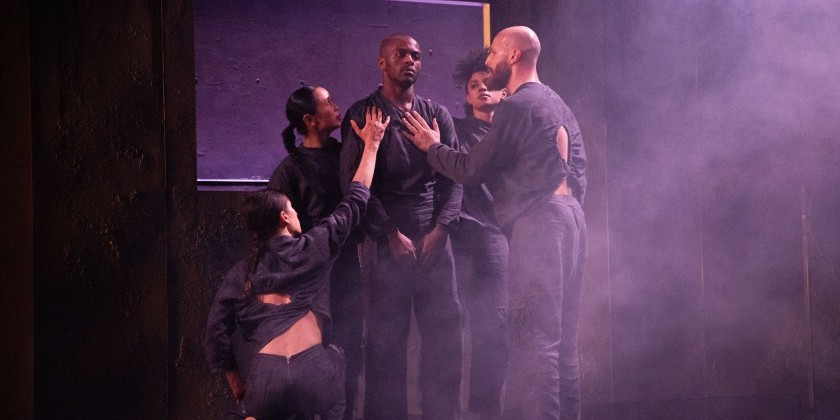

Kyle Abraham finds other things to love in Cunningham’s work. He notices the isolation of body parts, the curving multi-dimensionality, and the risk-taking. His duet MotorRover, however, has a lyrical and emotional flavor that carry it to the edge of what might still be called “pure dance.” When, at one point, Claude “CJ” Johnson and Donovan Reed embrace, we see two people holding each other, and not a random intersection. Similarly, the “borrowed” elements—the petits battements and finger shaking moves—never quite seem to lose their previous associations. Johnson and Reed exhibit a gravity that recalls the absence of emotional affect in Landrover, while passing from delicate balances to athletic leaps. Yet this duet implies a human connection. When these dancers cover ground and launch themselves in the air, we see the choreographer exploring space, but we also feel exhilaration.

As a catalyst for the creation of new dances, In Conversation with Merce is entirely successful. Where there was one marvelous duet, now there are three. And yet a critic who is aware of the context cannot leave this scene without carping. For like other efforts of this kind—the 1999 Duets for Martha and the Lamentation Variations commissioned by the Martha Graham Dance Company—In Conversation with Merce implies that historic dances have value only insofar as they provide fodder for novelties. Yet no excuse, or apology, should be required for the preservation of masterpieces.

Despite what is now a long history, modern dance remains stuck in the present, a transitory moment that it continues to mistake for the future. This narrow idea of “relevance” is, in part, what led to the death by Kool-Aid of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 2011. And while personal freedom has always been central to the philosophy of modern dance, now we are beginning to see the risk that comes with glorifying the new at all costs. Disdaining the great achievements of the past plays into the hands of those who would erase our memories the better to mechanize and enslave us.

Maturity means understanding that the past is not a burden. To evolve as human beings, we must both create and preserve.