IMPRESSIONS: Baye & Asa's "4/ 2/ 3" at Baryshnikov Arts Center

Featuring: Frances Lorraine Samson, Janet Charleston, Kyle Martin, Lily Gelfand, Megan Siepka, Mikaela Brandon, Nick Daley, Leora Champagne, Kristen Lieng, Sasha Lecoq

Choreography & Direction: Baye & Asa

Composer: MIZU

Lighting Design: Serena Wong

Costume Design: Dominique Kelly

Scenic Design & Fabrication: Soren Kodak

Stage Manager: Chelsea Gillespie

Company Manager: Ankita Sharma

Date: March 28, 2024

What has 4 legs in the morning, 2 legs at noon, and 3 legs in the evening? The Sphinx asked Oedipus this question in Sophocles’ play, Oedipus Rex, in 429 BC. At the Baryshnikov Arts Center in 2024, choreographers Amadi ‘Baye’ Washington and Sam ‘Asa’ Pratt use this riddle as an allegorical structure for their latest collaboration, 4/ 2/ 3. As Oedipus discerned, the answer is man: crawling as an infant, walking on two legs as an adult, and using a cane in old age. Washington and Pratt divide their work into three sections to represent three generations of performers, and reflect on humanity’s industrial history and collective search for blame.

The setting is postapocalyptic and stark. A structure that looks like it is made of concrete looms at the rear of the stage, dark and uninviting. A cylindrical chute protrudes from a wall sporadically emitting white smoke, next to a door and a large, glassless window. Composer Mizu's sound score, equally ominous, layers ambient cello chords with the sounds of screeching metal and hissing steam. The children (Leora Champagne, Kristen Lieng and Sasha Lecoq) lope across the stage in bear crawls and circle each other as if playing Ring Around the Rosie. All excellent performers, they move though the space as if it is their playground and not an industrial wasteland, climbing on the metal chute like a jungle gym. Occasionally, they look warily at the gaping window.

Suddenly their play becomes aggressive. They throw one another to the ground, and drag each other across the stage. Something dark is afoot.

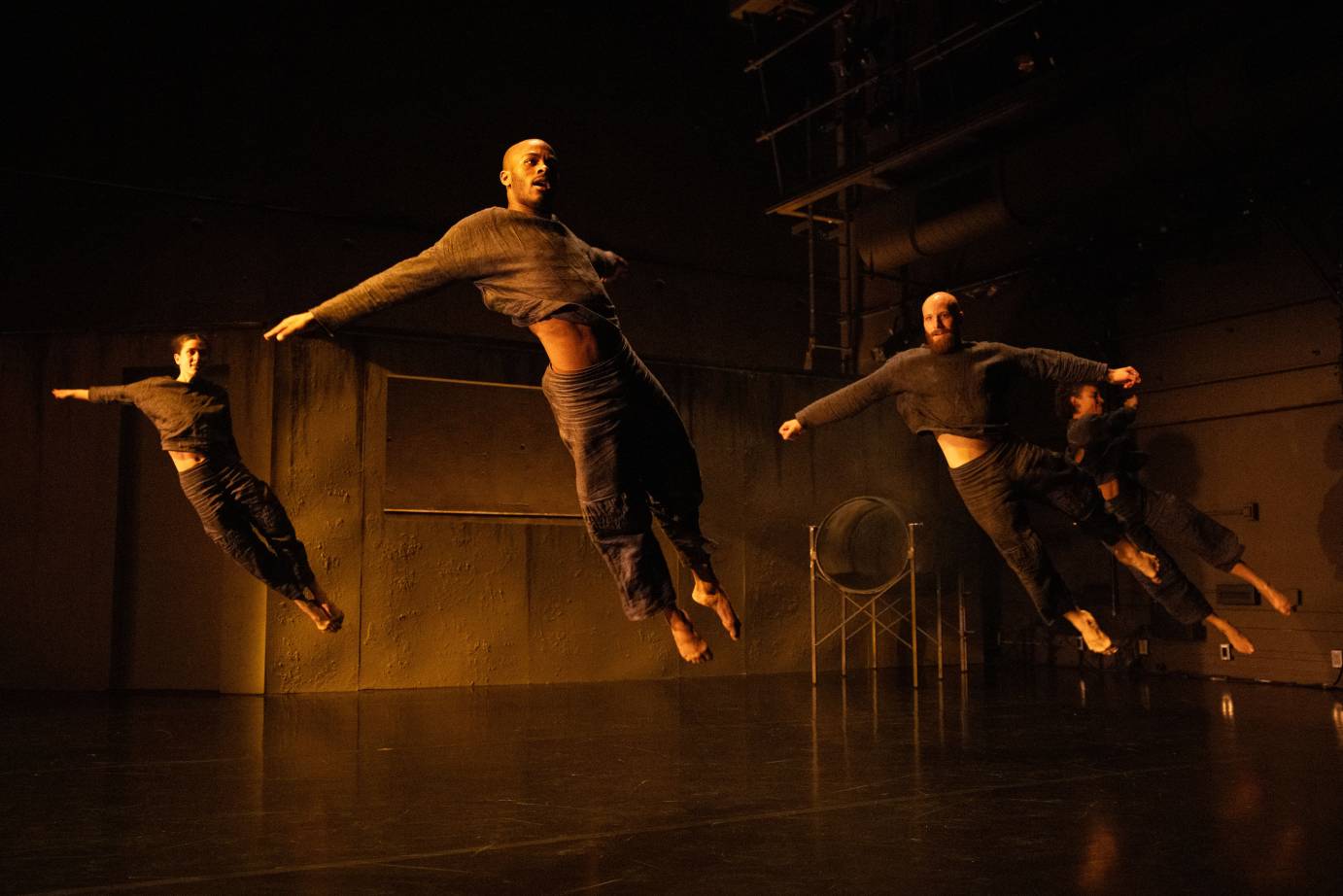

This sense of doom is amplified as section two begins. Six adult dancers (Frances Lorraine Samson, Kyle Martin, Lily Gelfand, Megan Siepka, Mikaela Brandon, and Nick Daley) ooze out of the smoking tube, melting onto the floor. While some of their movements mimic the children’s games, their interactions appear less playful. They build unison patterns with resolve, yanking one another into intricate cat’s-cradle formations, as if forging a new society where not everyone agrees. Their determined intermixing becomes faster and more forceful as they settle into a rhythm, finding order within chaos. The choreography is feral and mesmerizing. Weighted yet buoyant, the dancers devour the space around them. They bound across the stage in low lunging strides then suddenly alight in surprising lifts and jumps, masterfully executing complex and athletic choreography with profound precision. Moments of suspension and flow within the quick, percussive movement patterns are especially pleasing, and as the choreography becomes more elaborate, a sense of journeying emerges.

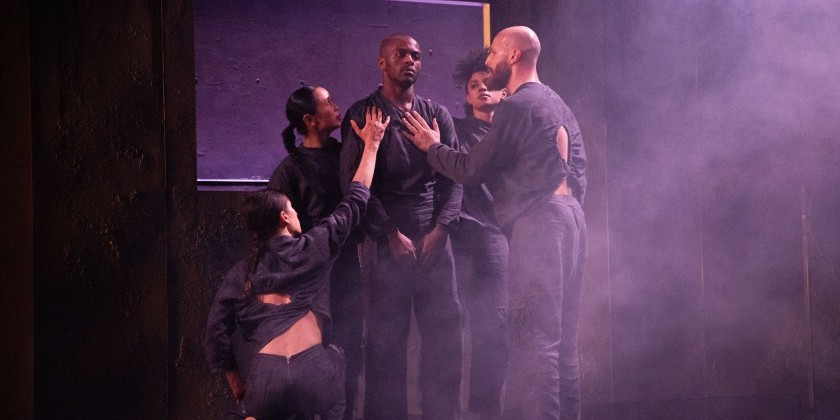

Like the children before them, the adults cast foreboding looks toward the building behind them, but when the door finally opens the dancers are able to pass through with ease. However, as one after another exits and reenters, the mood shifts. The performers stop to watch each other, isolated in frenetic solos, no longer moving as one. There is menace in the way they observe, aggressively circling, cautiously avoiding contact. Eventually Nick Daley climbs on top of the chute, twitching and pointing like a crazed cult leader. The others sink to the floor enraptured. When they rise, they clump together once again, only this time like a spectral horde, obedient to their demonic lord.

Serena Wong’s minimal lighting design enhances feelings of threat and isolation. The lights continually shift angles, brightening parts of the stage and throwing others into darkness. Solos arise in these bright patches, the dancers suddenly vulnerable as others lurk at their edges like predators. All sense of community vanishes as each dancer takes a turn under the spotlight, accused. Two figures appear in silhouette at the window- ghosts of the innocent children these adults used to be.

Janet Charleston brings wisdom to the final section. Where the children were less refined and the adults angsty and angular, Charleston moves softly with an easy flow. She brings gravity and solemnity to familiar patterns, repeating earlier movements in a more contemplative way. Two more ghosts at the window, one child and one adult, witness her solo, which is peppered with moments of stillness as if she is lost in the act of remembering. While the warning about man forging his own demise through the relentless pursuit of progress and technology is not a new message, it is also not a tiresome one.

When the rest of the cast joins Charleston on stage, slowly walking as one symbiotic unit, there is a sense of resolution. Perhaps they have learned from their past mistakes. But as one of the children strays from the group, drawn again toward the smoking chute as the lights fade, the eventual repetition of the past seems more likely.