IMPRESSIONS: Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company's "Story/Time" at the Alexander Kasser Theatre of Montclair State University

Sunday January 29th at 3pm

Conceived and Directed: Bill T. Jones

Choreographed: Bill T. Jones with Janet Wong and members of the company

Featuring Bill T. Jones

And the company: Antonio Brown, Talli Jackson, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, LaMichael Leonard, Jr., I-Ling Liu, Paul Matteson, Erick Montes, Jennifer Nugent, Jenna Reigel with Ted Coffey

Music: Ted Coffey; Text: Bill T. Jones; Decor: Bjorn G. Amelan; Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel; Costume Design: Liz Prince

The task he gives us is to sense a minute; once we feel it’s over, we must raise our hands, and keep them up — no cheating. Simple enough. And who could refuse a request from Bill T. Jones? Even walking out on stage to casually chat and share his sadness about the end of a great run of Story/Time at the Kasser Theater, he commands the space with a larger-than-life force. Hypnotized, some of us raise our hands way before the minute is up. Our sense of timing is so poor in fact, Jones makes us start again. “Must have been a good weekend,” he chuckles to some anxious sucker in the orchestra. “One more time.”

The stage manager, Kyle Maude, measures out a minute — actually much longer than I thought. OK. That’s it. Our conceptual warm-up is finished. “This work will be filled with seventy of those,” the casual Jones easily explains. Then the performer Jones takes his place behind a simple white desk preparing to read. The story begins.

Story/Time is Jones’ 2012 artistic response to John Cage’s 1958 work, Indeterminancy. That performance found Cage, the gentle voiced avant-garde who would have been 100-years-old this year, sitting alone at a desk reading a stream of stories at various speeds while his musical colleague, David Tudor, located somewhere not within earshot, randomly played excerpts of Cage’s compositions. It was an experiment in storytelling, music, time and chance and, according to the Smithsonian Institutions Folkways Recording Label, a “wonderfully curious way to hear stories.”

Jones questions his place in the modernist tradition by placing himself in a similar context — a man completely different than Cage, in another century contemplating stories, time, and chance — though not with his musical compositions, but with his dances, a music collaborator, and a futuristic yet spare set.

.jpg)

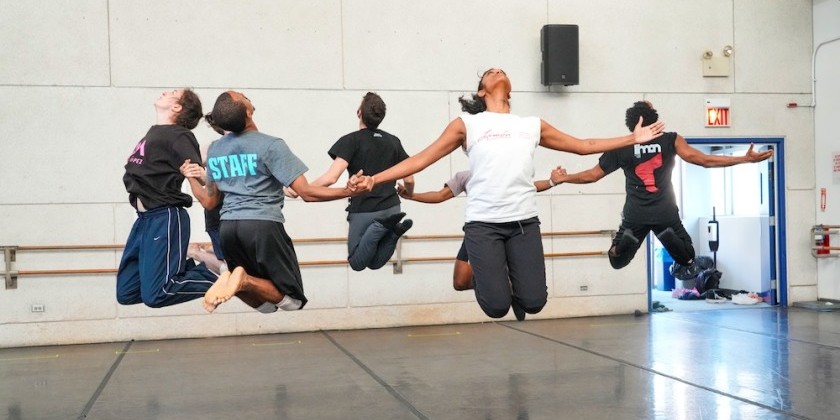

Story/Time, like the work that inspired it, proves a wonderfully curious way to hear stories, not just for the way in which we hear Jones’ rich tales and observations, but for the way we don’t. Wanting to cling to every gem, we can miss bits by being distracted, or rather attracted, to the arresting presence of dancers catapulting around stage. The dancers — angels and acrobats — fly, contort, jiggle and are sometimes dead still. Whatever their task, it is difficult not to be riveted by these gorgeous folk.

Then there is the sound score by Ted Coffey: chimes and clangs, that I notice when I am not paying attention to words or movement. Coffey underlines and enhances the action or sometimes blots it out entirely making it impossible to hear what Jones is saying. In our matinee performance, this induces laughter. In a 1981 interview with Merce Cunningham at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, John Cage said of the difficulty of hearing music, “We are more involved with our eyes then our ears.” It’s true. But what sound can do that events on stage cannot is surround us. Coffey chooses to highlight this fact when Jones talks about Arnie Zane’s death. Jones’ stage mike muffles, and his words only come to us from behind — an eerie shift.

I gather when the text and dancing sync it’s chance, yet there are times when the dancers seem the very breath of the stories, directing our attention to important details. When Jones recalls a memory of Merce Cunningham, the dancers stand in a semi-squat, backs erect, wobbling their bowed-out knees as if to remind us of Cunningham performing into old age. When he speaks of the flood of Noah and describes waters rising high above the mountaintops, a few dancers roll across the floor as stage fog slowly envelops them. Suddenly we see all the animals on earth submerged and sadly churning along with the currents. When words transport us from the great flood to an ancient dwelling place on a mesa in New Mexico, gleaming, naked bodies emerge from the smoke to guide clothed, earthly figures across the stage. They slowly haul office furniture, a large sofa and a swiveling desk chair, of all things. They could be carrying their troubled lives across the River Styx toward the light of the Elysian Fields. It is transfixing how elements come together to create their own stories.

As stories bubble up and fall away, the clean, elegant playing ground where the action occurs composes us. The desk always remains in the same spot, center-ish, on a grid of twelve squares of equal size. The squares are numbered one through twelve in bright green illuminated numerals. They could represent the twelve months of a year, or the twelve hours that compose half a day, or the twelve signs of the zodiac. There is a digital clock, also with illuminated green numbers, that appears behind Jones and later off to our right. It reminds us that no matter what, time marches on. Bright green apples line the desk. The pairing of green and white, both calming and efficient, invites the eye. There is a story at the beginning of the piece about apples, which I didn’t pick up, but just looking at those simple green orbs on the “teacher’s” desk, I want to take a bite.

Bill T. Jones' Story/Time; Photo by Gene Pittman, courtesy of Walker Art Center

There is so much to take in. Personal stories: Estella, Jones’ mother; Arnie Zane, his lover and partner; relatives, friends, great artists, odd meetings. Bessie Smith is singing about boiled cabbage; Estella said something about John Henry and the graveyard; the mom at the Washington Square Fountain; the prostitutes in the windows in Amsterdam; adobe, the touch of a hand, French fries floating in a flooded McDonalds; the month of March that will never be the same for that is when Zane died. Here are the details that make a life: great and small joys and tragedies and sparkly minutiae. We see the tasks that shape time. We hear the sounds that co-exist with, enrich and jar it. We are reminded of larger myths we change to suit our needs. Much happens in Story/Time. What do we grab on to? I decide to let myself be mesmerized. That feels good.

Questions arise as all of our stories and senses of time mix together. What is the difference between listening and hearing, seeing and perceiving, recalling and repeating? How do we sense a story even if we don’t hear the whole thing? Why is it when Jones’ talks about New Mexico I see “my” childhood there, for example, and not just his story? What is silence? What is music? What do we capture out of all of this? What remains? We — with our varied, inconsistent perceptions — are as much chance elements in this work as Bill T. Jones, Ted Coffey, and the dancers.

In the 1981 interview where John Cage and Merce Cunningham speak of their work together, Cage mentioned that before he used the I-Ching, he explored the possibilities in his creative field with questions. He was interested in radical questions because “they explore the roots rather than the surfaces,” and he described radical questions as ones that open doors. Bill T. Jones and his collaborators open a floodgate.