IMPRESSIONS: Gibney Company at The Joyce: The Spirit of Experimentation, Then and Now

Company: Gibney Company

Artistic Director: Gina Gibney

Company Director: Gilbert T. Small, II

Choreography: Twyla Tharp, Yue Yin, and Jermaine Spivey & Spenser Theberge

Date: May 11, 2024

The Gibney Company, now an adventurous repertory group, brought four works to The Joyce Theater on May 11, 2024. Among them were one terrific revival and one fascinating premiere.

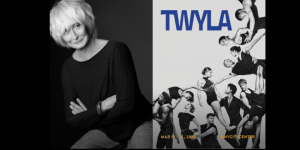

For her astonishing 1970 trio, The Fugue, Twyla Tharp made a 20-count phrase and wrung every possible variation from it: double-time, slow, broken, flowing, stomping, floating, directional changes, canon, retrograde, et cetera. As you watch it, the innovation just keeps coming. In her biography of Tharp, Marcia B. Siegel called it a “flood of invention.”

When it was performed in 2017, Kara Chan of Twyla Tharp Dance said, in an interview posted by The Dance Enthusiast: “There’s a mental resiliency and attunement to command the movement.” The audience needs to have a similar mental resiliency. We have to be wide awake. When there is no story, it frees us to concentrate on the dancing. In The Fugue, the drama comes from the changes in tempo, texture, and spatial relations. The music comes from the sound of the boots mic’ed on the floor. We pay attention to how a dancer softens when bending over, how slicing arms lead into slow, arcing legs. In movement # 20 the leg slaps open to the side while the arms close across the chest. We start to recognize this move as a definite finish. Yet sometimes it keeps going.

This current version of The Fugue, staged by Shelley Washington, begins with just Graham Feeny and Eleni Loving onstage. Their dancing is energized, precise, and pristine. When Eddieomar Gonzalez-Castillo enters, he brings a certain warmth. Sometimes Feeny gives the tempo by tapping his thigh. Tharp often plays with two against one as counterpoint. So when all three re-enter upstage, scattering the fast variation like tossed pebbles across the water, it's a delightful surprise.

These dancers are super committed to the movement. But in my memory, the original trio had a touch of defiance. Back in 1970, the three Tharpian superwomen — Sara Rudner, Rose Marie Wright, and Tharp — were stomping the hell out of it.

The shorter, gentler Tharp revival that opened the program, Bach Duet (1974), starts with two functional gestures: spitting on the floor and kneading the foot into the wet spot to gain traction. Tharp builds on those two brief actions, showing us how something can be made from nearly nothing. You don’t need a story; you don’t need a mood. Like the four onstage musicians and one singer performing Bach’s 78th Cantata, Miriam Gittens and Jake Tribus stay in a circumscribed area. Floating through shimmying, head tilting, shuffling, and upper body circles, they exemplify Tharp’s supreme ability to create a continuous thread out of disparate moves.

Yue Yin's A Measurable Existence (2022) is all mood. The dungeon atmosphere — light beams coming only from high up (lighting by Asami Morita, adapted by Tsubasa Kamei) — and ominous music (original score by Rutger Zuydervelt) feel threatening. Jesse Obremski and Jie-hung Connie Shiau glom onto each other, desperate but resilient. They cling, drag, and use circular pathways to make sinuous figures 8’s. A startling moment comes when a diagonal pipe with two lighting instruments lowers down to scorch them in red light. This doesn’t seem to faze them. The dance ends with Shiau standing alone, to brave the elements on her own. (In other performances her role is played by Tribus.)

The premiere, Remains, is choreographed by the formidable team of Jermaine Spivey & Spenser Theberge. This duo typically allows the dancers to contribute by fulfilling certain “tasks.” (When Anna Halprin first used the word “task” in the 60s, she meant functional movement like carrying a tree branch. For Spivey and Theberge the task is more complex and could be emotional as well. In this case, they have asked the dancers to allow their past life to remain in their bodies.) Although Remains is nothing like The Fugue in process or structure, it does have an open, experimental feeling, as opposed to being mired in moodiness.

Shiau, lively and natural throughout the evening, starts Remains by dancing alone, surrounded by a circle of the eight other company members. One of them, Obremski, is stuttering into the mic: “It’s….. it’s… it’s…. all…. all… about….time…. time.” (text by Theberge) Shiau’s dancing is continuous, but she occasionally lets the stutter affect her as she momentarily goes back and forth over the same track. Another uttered phrase was “What …. What … I’ve …I’ve…all…all..always …..wanted…..wanted….” While the verbal statement of desire was clearly hampered, the dancing desires were going full steam ahead.

The solo moments are highlights. Tribus throws himself off-balance with a long mic stand, never losing his strength and fluidity. Loving’s solo, with quick changes of direction, happens upstage when everyone else is lying on their backs. It’s almost like they’re playing dead and she’s an angel who brings them back to life. Feeny’s solo, breathless and full bodied, seems to emerge from his caring contact with other dancers.

Some sections are structured improvisations even in performance. Occasionally someone yells out a number and some of the dancers react — or not. At first, I thought #10 was a pivot in place, but another time it wasn’t. Maybe #1 was lifting the arms into high fifth. In any case, the combination of the gorgeously complex dancing and the feeling of randomness was intriguing.

What’s exciting about the current Gibney company, under the direction of Gilbert T. Small II since 2022, is that the dancers invest the movement with personal vitality, they react to each other with exquisite sensitivity, and the rep is a stimulating mix of old and new.