DAY IN THE LIFE OF DANCE: "Crafting The Ballet Russes" at the Morgan Library & Museum (Part 2)

BALLETS RUSSES: THE ROBERT OWEN LEHMAN COLLECTION

WHO: Organized by Robinson McClellan, Associate Curator of Music Manuscripts and Printed Music

WHEN: June 28 - September 22, 2024

A striking feature of the exhibition Crafting the Ballets Russes now at the Morgan Library & Museum is the way it illustrates the evolution of modern art within Diaghilev’s company. Beginning in 1910, a careful selection of objects suggests the complex origins of L’Oiseau de Feu. The neo-nationalist movement in Russia had paved the way for this ballet, yet the stylization of Léon Bakst’s costume designs and poster art, his figures flattened yet alive with organic movement, shows him far in advance of Ivan Bilibin, whose story-book illustration appears nearby — not to mention Viktor Vasnetsov, another precursor whose fairy-tale paintings never left the stodgy world of 19th-century realism.

After contributing enormously to the success of the Ballets Russes’ first seasons, however, Bakst and another key member of Diaghilev’s team, Alexandre Benois, would be sidelined. Nicholas Roerich, whose costume designs for Le Sacre du Printemps involve fur and animal skins, had his moment; but Roerich would quickly be left behind in favor of avant-garde painters like Natalia Goncharova and her husband, Mikhail Larionov. Goncharova looks demure in a quaintly realistic self-portrait of 1907. Seven years later, however, this wild woman would appear bare-breasted, with futurist designs scrawled on her face and bosom in the avant-garde film Drama in Cabaret No. 13. Though still attached to folk art, Goncharova and Larionov were experimentalists, and the inventors of Rayonism. Imagine Goncharova’s surprise, then, when in due course Nijinska would reject her early designs for Les Noces as old-fashioned! (“The chair’s not necessary, the comb is not necessary, and the hair-combing even less so,” Nijinska told Diaghilev.)

One could not find a starker contrast than that between Goncharova’s 1915 curtain design for Les Noces, a brightly colored and intentionally child-like evocation of folk art in the style of Le Coq d’Or, and her ultimate designs of 1923, which at Nijinska’s insistence became sere and spiritual. Nijinska, who is quoted nearby as saying that “I listen to music through my eyes,” had fully absorbed the aesthetic ideas of Wassily Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art, and had developed an abstract language of her own. That Vaslav Nijinsky had also traveled far in this direction is evidenced by his diary, with its exaltation of “feeling,” and by his Cyclopean painting Mask of God.

The path forward was not always smooth, however, and not everyone desired to follow it. Benois, for instance, never changed his style. The designs of this charter member of the Nevsky Pickwickians forever retained nostalgic tints, an air of mysticism, and a self-conscious theatricality. A comparison between Benois’ set designs for Petrouchka (1911) and Boléro (1928) is instructive. Both contain the interior frame typical of Ballets Russes decors, suggesting a play within a play and archly emphasizing the unreality of the spectacle. In Petrouchka, the interior frame is like a second proscenium complete with raised curtain; and fanciful figures in Russian costume appear inside its painted windows. The bustling fairground occupies the middle ground, and the scene telescopes to focus on yet another stage, the puppet booth with its mysterious sign advertising the “Theater of Living Figures.”

In Boléro, meanwhile, the interior frame consists of the massive draped curtain at left, and the timbered support at right, while the stage within the stage is a round wooden table. This design helps us to interpret the ballet, which (pace Maurice Béjart and Bo Derek) is not primarily about sex, but once again about the life of the theater. This Boléro portrays artistic ecstasy and the seductive power of music as both the Dancer and her public become increasingly inspired. In his catalog essay, McClellan quotes critic Louis Laloy, who perceptively observed, “without lascivious writhings or provocative gestures… she attends only to the call of the music, which is the soul of the dance.” We are not so far, here, from the scene in Petrouchka where the Charlatan’s flute hypnotizes a young girl in the crowd. Though apparently reprising her femme fatale role as the Dancer, Rubenstein was 45 at the premiere of Boléro — a seasoned artist, not a sexpot. Nijinska choreographed her solo as a single, extended phrase which unfurls but never repeats.

The Ballets Russes also encountered a major challenge during and after the First World War, when what we might call a “culture war” erupted in France, and the greatest successes of the company’s early years began to be branded as the decadent products of German influence. Cut off from home by the Russian Revolution, the Ballets Russes were forced to change their approach to modernism. For a full account of this development, Kenneth Silver’s 1989 book Esprit de Corps: the Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914-1925 makes essential reading. Silver quotes art critic Louis Vauxcelles, for instance, who wrote: “After the war of cannon fire, another war, on the terrain of the industries of art, will have to be vigorously pursued.”

This second front (not Benois’ love of Versailles, nor the Russian concerts of Wanda Landowska) precipitated a change. It explains why, after the Great War, Diaghilev, who had been an ardent Wagnerian, began to rail against the corruption of “Boche” music. It explains why the Orientalism of Schéhérazade became suspect (Turkey had sided with Germany); why Parade was accused of being “unpatriotic” (eventually leading Erik Satie to compose Socrate); and it explains why Stravinsky got busy composing neo-classical works including Pulcinella, Mavra, Apollon Musagète, Oedipus Rex, Le Baiser de la Fée, Perséphone, etc.

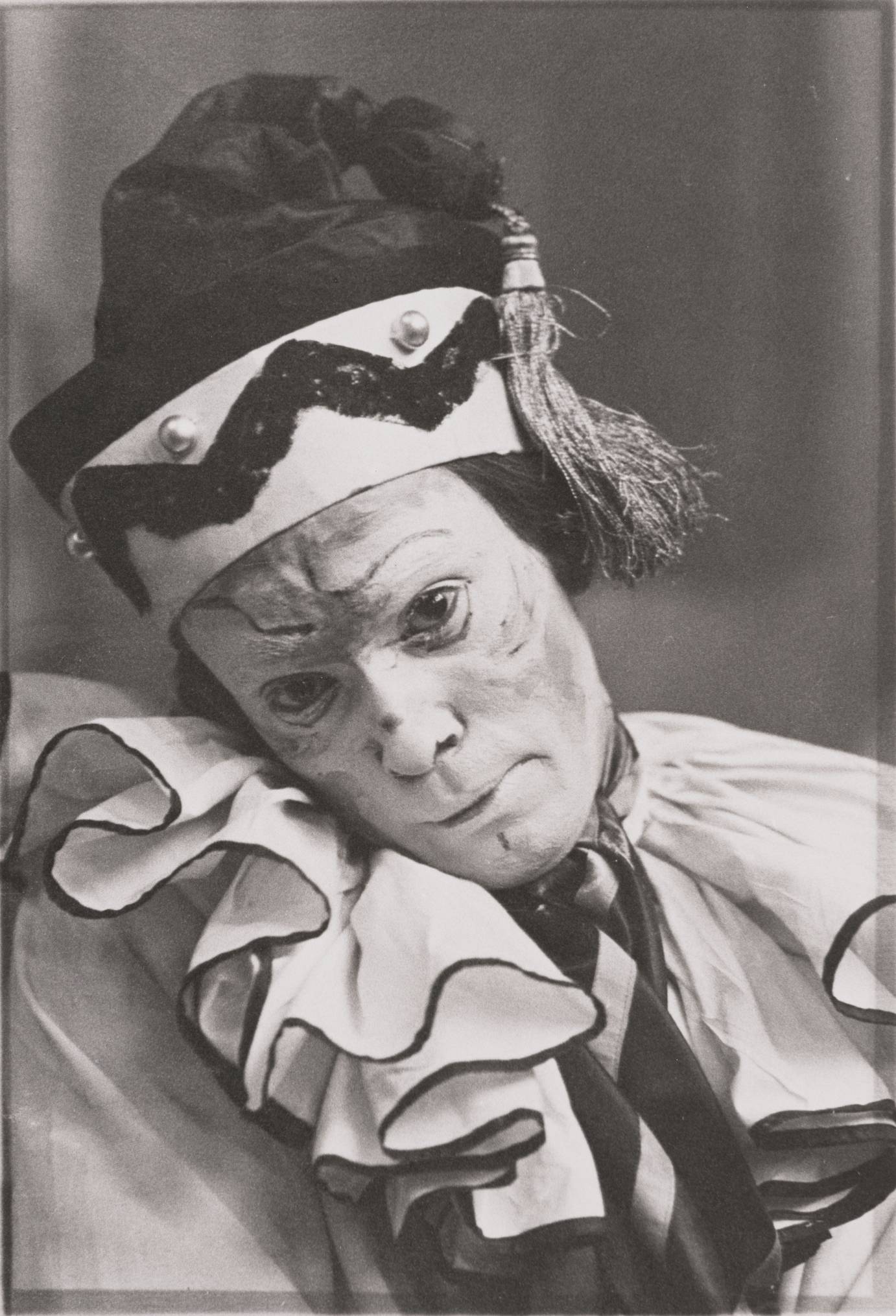

When Nijinska returned to the company after a period of isolation in Kiev, she was in for a shock. Crafting the Ballets Russes captures the company’s aesthetic turnaround, juxtaposing a futuristic self-portrait in which Nijinska resembles a visitor from outer space with an illustrated program featuring images of The Sleeping Princess and Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur. These tensions would only resolve themselves in ballets that managed to be both classical and modern: Pulcinella, Les Biches, La Chatte, and Apollon Musagète.

Ironically, it may be in the 18th century that Diaghilev, the great promoter of modernism, found his unflagging dedication to the new. A great deal has been written about the influence of the commedia dell’arte on the Ballets Russes (see, for instance, J. Douglas Clayton’s Pierrot in Petrograd). Yet another source may be the extraordinary Pulcinella frescoes that Giandomenico Tiepolo created for his family villa in Zianigo, outside Diaghilev’s beloved Venice. The capstone of this series in which clowns emerge from the bowels of the earth to take up typically aristocratic occupations, is the fresco Il Mondo Nuovo formerly in the adjacent portico of the villa.

Here we find a scene suggesting an Italian version of the fair-ground in Petrouchka: eager spectators have gathered to see the wonders of the New World portrayed in a magic lantern manipulated by a showman standing on a stool. Three figures in profile frame this composition. On the far left, a Pulcinella with a dumpling on a fork seems to taunt the artists, Tiepolo and his father Giambattista, the former raising his monocle to his eye, the latter with his arms folded indignantly. This fresco, and the nearby scenes of Pulcinellas romping, together form an allegory of revolutionary social change and the decline of the aristocracy.

Tamara Karsavina and Michel Fokine in The Firebird. Source unknown

As Diaghilev began his career, a similar revolution was coming to his homeland, Russia. He foretold it in his “Hour of Reckoning” speech delivered in conjunction with his exhibition of historic portraits at the Tauride Palace. Imagine, then, what Diaghilev’s emotions may have been, when he beheld Tiepolo’s fairground scene and considered its implications. The Mondo Nuovo seemed to offer him a choice, and a possible future. He could stand proudly with arms folded, rejecting the vulgar tide of change, or he could study and embrace it finding a source of vitality and renewal in the rough antics of the commedia. We know what choice he made. In the Mondo Nuovo we can identify Diaghilev both with the younger Tiepolo, an aristocrat and aesthete overcome by curiosity, and with the figure of the showman. Wielding his unequaled connoisseurship like a saber amid revolution, war, and successive waves of modernist upheaval, Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes would challenge and amaze the public with an unending carnival, with visions of a New World of art both playful and profound.