American Ballet Theatre's Fall Season Featuring Jessica Lang's "Her Notes," Benjamin Millepied's "Daphnis and Chloe" & Others

David H. Koch Theater

New York, NY

Oct. 19 - 30, 2016

Attended a number of programs that featured the following repertoire:

Oct. 19: Serenade After Plato's Symposium, Symphonic Variations, Brahms-Haydn Variations

Oct. 21: Brahms-Haydn Variations, Her Notes, Daphnis and Chloe

Oct. 23: Her Notes, Serenade After Plato's Symposium, Brahms-Haydn Variations

Pictured above: Gillian Murphy in Brahms-Haydn Variations.

American Ballet Theatre's fall repertory season is always a welcome opportunity to get to know all the dancers, throughout the ranks, more fully, in a theater more ideally suited for ballet than the Met. The classy repertory for this two-week season included challenging works by A-list choreographers – Ashton, Balanchine, Tharp, Ratmansky – with contrasting casts featured in each.

The season's two additions to the ABT rep were of notable interest. Both were by experienced, prolific choreographers. Interestingly, both Jessica Lang's Her Notes and Benjamin Millepied's Daphnis and Chloe featured substantial – sometimes intrusive – sets in which sizable pieces rose and descended for different sections,

Commissioning a world premiere from Lang was a smart move. She has not only created works for the ABT Studio Company, but has been maturing as a choreographer with her own five-year-old troupe and through commissions for increasingly major ballet companies – most recently, Pacific Northwest Ballet. It seemed the appropriate moment for her to work with the company – and for the company to offer a premiere by a female choreographer.

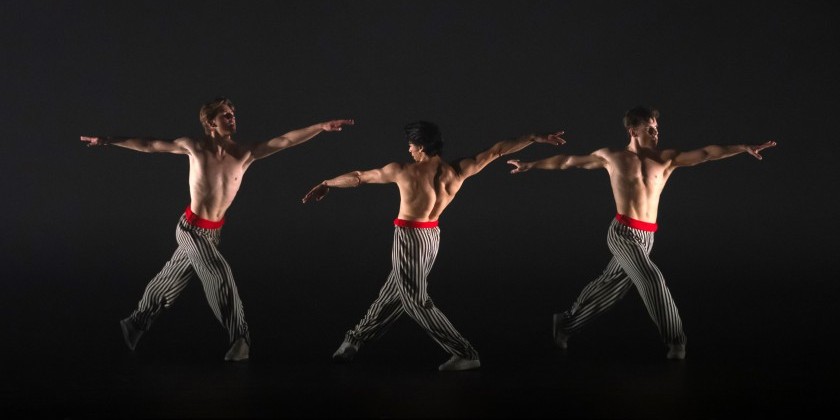

Lang set Her Notes to five sections of Das Jahr, an eloquent 1841 piano score by Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel in which each section represents a month of a year spent in Italy. Ten dancers – six women and four men, with two couples being given prominence – are set in motion through wistfully pretty abstract passages that at times suggest an evocation of memory. The atmosphere varies from youthful brio to wistful regret.

Lang has created a refined, tasteful, hermetic work. It's full of atmospheric and inventive passages, but too often it seems to confine the dancers rather than set them free. There are moments of sculptural beauty – carefully assembled group poses, sometimes in silhouette – that don't exist within any context. If we're being shown portraits of these people, they remain only outlines.

Gillian Murphy and Marcelo Gomes emerge as the primary, more mature, couple while Misty Copeland and Jeffrey Cirio are a fleet, more vigorous pair. The partnering – especially for Murphy and Gomes, tends to look labored and even ungainly at times. At the premiere, Lang's ballet followed Tharp's Brahms-Haydn Variations, in which the same pair reigned as exuberant monarchs. So their subdued aspect in the new work was a notable contrast.

The set, designed by Lang, has a large outer framing panel with a central opening. Within that is a smaller square panel with a window-like cutout. As the ballet opens, the stage picture is pristine and elegant. But as they rise and lower in seemingly arbitrary – and sometimes clunky – combinations, the set pieces become intrusive. Bradon McDonald's mainly soft gray costumes – especially the women's, with their pale blue or green underskirts – are pleasing and gently romantic.

Millepied's Daphnis and Chloe was made for the Paris Opera Ballet in 2014. One can understand his being drawn to Ravel's lushly textured, dramatic, nearly hour-long score – but it seems to have stymied him. There are five main characters identified in the program, but the ballet is almost defiantly abstract. Incidents and encounters occur because the original scenario decrees that they do, but we get no sense of motivations or relationships. The ballet is more generic than atmospheric.

This sense of the soloists being marooned occurs early on when, after a pleasant enough, sensuous yet invigorating opening section for the large ensemble, Cory Stearns and Stella Abrera appear as the central characters – as if their being a couple is already an established fact we have to accept. Their various separations and tribulations unfold dutifully, amid extensive ensemble sections (willowy nymphs! robust pirates!) that give little indication of character or drama.

The music is gorgeous, but the ballet feels defeated by its expansiveness. The appearances of Daniel Buren's heavy set pieces – colored geometric shapes that are lowered and raised frequently – quickly become arbitrary and distracting.

A word of thanks to ABT artistic director Kevin McKenzie for his ongoing devotion to the works of Frederick Ashton, whose Monotones (1967) and Symphonic Variations (1946) were revived. Just as Balanchine said that Allegro Brillante contained all he knew about classical ballet compressed into 17 minutes, one might imagine Ashton saying the same about the pristinely intricate Symphonic Variations. Calvin Royal and Christine Shevchenko displayed gleaming elegance in the opening night performance, but everyone in both casts demonstrated reverent devotion in taking on its rigorous purity.