IMPRESSIONS: Miki Orihara in Resonance lll at LaGuardia Performing Arts Center

Bringing Modern Dances' Mothers Together

Choreography: Seiko Takata (1895-1977), Doris Humphrey (1895-1958), Konami Ishii (1905-1978), Martha Graham (1884-1991,) and Yuriko (1920- )

Pianist: Nora Izumi Bartosik

Music: Frederic Chopin’s Etude Op.10 Number 3 for Mother, Nikolai Karlovich Medtner and Gian Francesco Malipiero for Two Ecstatic Themes, Suguru Sasaki for Moon Desert , Zoltan Kodály for Lamentation, and André Jolivet for The Cry

Miki Orihara’s Resonance III, a beautifully executed solo concert honoring early Japanese and American founders of modern dance, carried us perfectly into the Mother’s Day weekend. After all, the featured choreographers birthed and nurtured a "new dance", one that could authentically express their innermost ideas and world experiences. Contemporary dancers and enthusiasts the world over owe them gratitude.

For Orihara, this evening has personal as well as universal resonance. With every step, she traces a rooted connection to her artistic predecessors across cultures. As the lights dim and rise on each work, we witness an evolution of modern dance in her body.

Seiko Takata’s Mother (1938) — tonight, its United States premiere— connects the inner life of the dancer to the music (Frederic Chopin’s Etude Op.10 Number 3) with delicate simplicity. Minimal action, caressing and cradling arms, soft traveling steps —the most forceful gesture being a breathy side arm extension— reveal the love of a mother for her child. A smooth glance up and outward on a diagonal speaks of hope for the future. One can see how Mother expanded upon the gestures of Dalcroze eurhythmics, a system connecting music to motion, which many of the early moderns studied.

Two Ecstatic Themes (1931) by Doris Humphrey encapsulates the abstract ideas of fall and recovery, hallmarks of Humphrey’s technique alive today in the work of the Limón Dance Company and its generations of students.

From a firm wide-legged stance, Orihara descends to the ground in yielding airy circles. Then with taut, direct, percussive moves, she rises to a climatic pinnacle away from it. Her white costume’s fitted bodice and flowing skirt accentuate her play with gravity. Humphrey referred to the moments between fall and recovery as “the arc between two deaths.” Such dramatic language — but the wording demonstrates a young artist’s intensity.

Konami Ishii’s (early 1930’s) Moon Desert —also being seen for the first time in U.S. — finds Orihara, in a sky-blue gown, brightened by glittering jewels, and sporting a white turban with a flowing train. She seems brought to us by the world of fantasy.

As she glides onstage, her upper body holds our focus. Whether raising her arms dramatically above her head, or grazing her hands along her face, she calls us to appreciate her beauty. Even as our dancer hastens to exit the stage, her arms continue to flit giddily at her sides. Does the dance end? I suspect this mysterious woman simply turns around to impart her glamour to some unseen audience behind the curtain.

Was Ishii inspired by the divas of early movies, or perhaps by meeting the doyenne of American modern dance, Ruth St. Denis on tour? What is the backstory? Ishii, a renowned expressive artist, trained the young Yuriko Kikuchi (famously known as Yuriko) in Japan. This concert has aroused my curiousity about the history of Japanese modern dance.

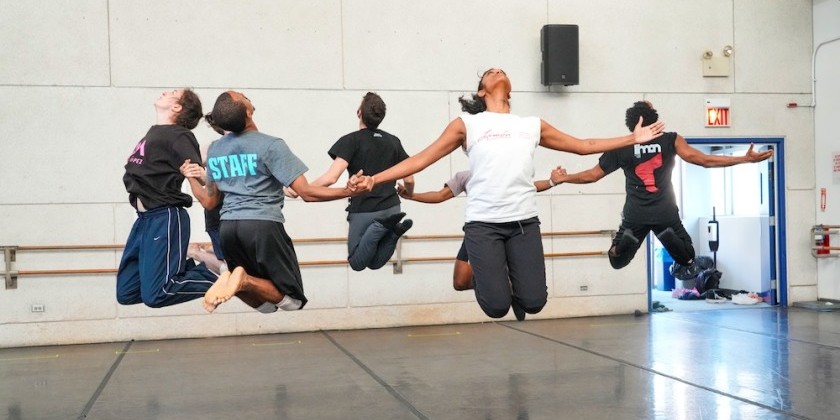

One of the unexpected pleasures of the night —besides the piano accompaniment of Nora Izumi Bartosik— is the collection of historical photographs shown between dances. The Japanese photos are new to us and their visual connection to early western dance images catches our eyes. (It reminds me of the excitement of discovering a family member in a distant place.) A photo of Konami Ishii’s pupils recalls students of Doris Humphrey or Isadora Duncan’s Isadorables.

Seiko Takata, offering incense to the gods, brings to mind exotic St. Denis.

The large projections radiate vitality and commitment. We can begin to appreciate how, from this small passionate band of people, a revolution began.

Orihara’s most stirring performances of the evening, however, came in Martha Graham’s Lamentation (1930) and Yuriko’s The Cry (1963).

Lamentation, a shockingly different work in the early 30’s because of its architectural, abstract approach to movement, still looks contemporary in 2019. The dancer, hidden except for feet, a partially revealed face and hands, remains seated on a bench, maneuvering fabric that encases her. Grief is masterfully distilled into angles that jut from a twisted core of purple lycra.

I’ve seen Graham’s iconic work many times, but Orihara’s magnetic interpretation is a new experience. Her energy smolders, subtly building, from the first agitated shifts, to her long pitched leans, to the sharp right angles of her arms. Instead of displaying anguish, she draws us in, quietly imploring that we know the depths of her sorrow.

The Cry depicts despair pliantly with supple twists and elastic knee bends, and it wonderfully travels. After witnessing the 1930’s presentational, frontally-oriented work, it’s great to jump into the sixties. Orihara carves the space of the stage, rolls to the floor, lifts her legs, and allows us register her back. Here her lament, as in the Graham piece before, is deeply felt, but not histrionic. Yuriko's note to the dancer: the dance is called The Cry, not your cry, or my cry. Orihara took that note to heart, making the piece universal.

While the evening recognizes all five choreographers, the soloist especially celebrates her mentor, Yuriko. In many ways the younger artist, followed her elder’s trajectory: both artists have roots in the US and Japan; both studied with some of the same Japanese teachers; they each danced for Graham,( with Orihara learning Yuriko’s roles), and both artists stretched beyond classical modern dance to Broadway, performing as “Eliza" in The King and I.

In a talkback after the show, Orihara confides that Yuriko helped her bear the Graham school when she arrived in New York in 1979. Excited to be in the US, not so much to dance, as to learn English, perhaps to drive (and see Mickey Mouse) Orihara described her first impressions of the Graham school, as “not a nice place.” Classes were competitive and she was elbowed and stepped on by students.

Yuriko, took the youngster under her wing, speaking corrections to her in Japanese. This caused the elbow jabbers to pause. Suddenly everyone wanted to know what it was the two were saying. Hmm. Orihara was accepted.

The rest, as they say, is history.

The Dance Enthusiast Shares IMPRESSIONS/our Brand of Review and Creates Conversation.

For more IMPRESSIONS, click here.

Share your #AudienceReview of performances. Write one today!