IMPRESSIONS: Thomas L. DeFrantz/SLIPPAGE’s “Soundz in the Back of My Head” at Gibney

January 11, 2020

Production Management: Shireen Dickson // Lighting Design/Performance: Asami Morita

Sound Design/Performance: Quran Karriem // Visual Design/Performance: Rebecca Uliasz

Concept/Text/Performance: Thomas L. DeFrantz

Approximately three-quarters of the way through his Soundz at the Back of My Head, Thomas L. DeFrantz makes a distinction between listening and hearing. “Listening, we all aspire towards,” he says. “To demonstrate empathy, to comfort . . . to move towards understanding, and becoming more aware of doing something about it. I hear things. I hear people say that they’re not racist, that they don’t see color, but they are and they do, of course. Why not see race for what it is and work through it towards the unknown place beyond disavowal?”

Gem-like observations such as the one above fly thick and fast in the third and final installment of his talkingdance series. In the program, DeFrantz calls it a “dialogic manifesto talking-dancing-technology work.”

For much of the hour-long piece, DeFrantz speaks, sometimes academically (he is a professor at Duke University), and other times personally. Reading from a treatise about the afterlife of slavery, he unpacks the narrow spaces afforded Black creativity and reveals the bond between Black artistry and fugitivity. He also relates an unfinished anecdote about an injury his brother sustained while playing football in high school. Regardless of the milieu, he is a compelling speaker — forceful in professor mode, vulnerable when sharing intimate memories.

Performed live, the audio and visual elements form a decoupage effect with the words. Quran Karriem’s score acts like darts, tossing tones and clangs through DeFrantz’s oration. Occasionally, they pierce a word, rendering it mute. In other instances, Karriem unleashes swells of symphonic music. The weep of strings and the blare of brass hang below the spoken phrases, adding a sonic plinth.

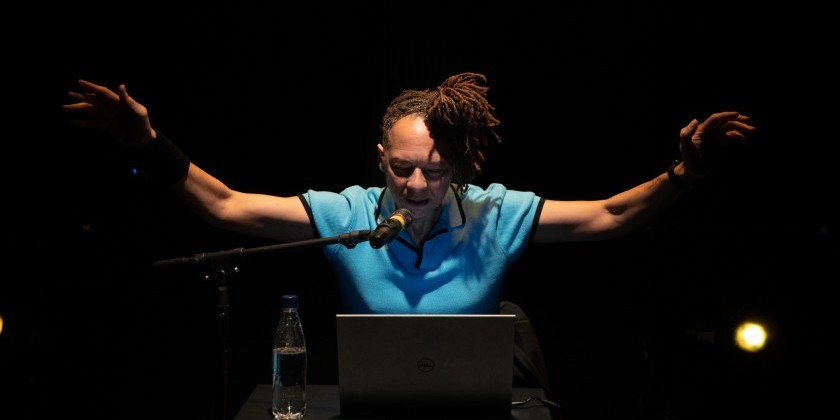

Asami Morita provides the lighting design and Rebecca Uliasz, the visual design. Buttery light follows DeFrantz as he promenades around the space where he periodically segues into a dance break of slicing gestures and, one time, knee crawls. When he pauses to speak into a microphone, a spotlight illuminates him. At the far end of Gibney’s Black Box Theater, films unspool intermittently. These include trippy hypnosis spirals and blurry motion-captures of DeFrantz. I find that, often, my ears are too busy for my eyes to give the interplay of light and shadow the attention they deserve.

With restless pacing, DeFrantz zooms through a variety of subjects. I wish a copy of his speech had been included in the program so that I could revisit it, linger over it. Even still, certain paragraphs implant into the gray matter of my brain, like fertile seeds. “Did you hear that?” he asks as an electronic tone brays. “If we could split the time of time, we could participate in a crucial world . . . We could move to the infinite Möbius strip, to resist the you not me, but imagine an abundance of we.”

I am listening.