Features > Impressions The Dance Enthusiast's Brand of Review/Thoughts on What We See

Highlights from Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM): Shen Wei, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, Robert Wilson & Mikhail Baryshnikov

Published on October 25, 2016

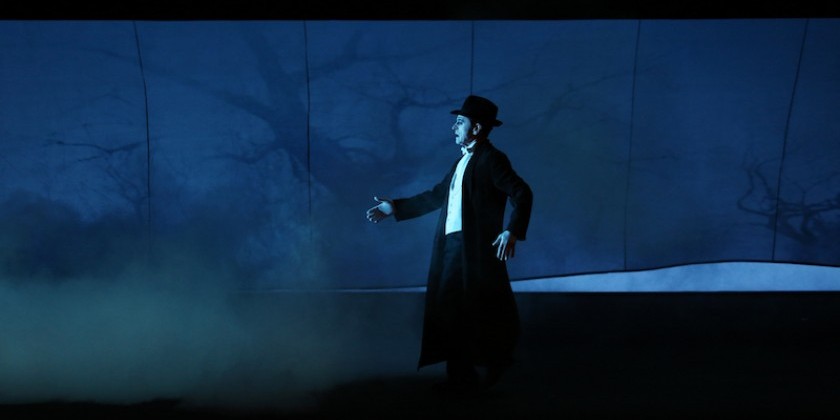

Mikhail Baryshnikov; Photo: Julieta Cervantes

BAM knows its audience. They want to be challenged. They want to think. And, they love to see their favorites. The three productions highlighted here are brave adaptations of singularly complex compositions, two musical and one literary.

Neither - October 7, 2016

Choreographer: Shen Wei

Cynthia Koppe and Zak Ryan Schlegel in Shen Wei's Neither; Photo: Stephanie Berger

Shen Wei’s choreography astonishingly evolves with the dramatic turns of Morton Feldman’s 1977 “anti-opera.” His eleven dancers often move in unison -- either in threes or noodling on independent paths with a limpid, boneless flow. Founder of China’s first modern dance company in 1990, Wei designs with an impersonal remove as though obeying Samuel

Beckett, who wrote in his 87 word libretto “till at last halt for good, absent for good from self and other.” The dancers surrender to an unknown.

Neither stretches the imagination, and tantalizes one with a series of enigmas. The audience in the Howard Gilman Opera House first encounters Shen Wei’s black and white Untitled No. 1, an oil and acrylic fanciful painting on a linen, rich with implications. Wei’s design talents gush throughout this hour-long work. His set with nine arched doors, once opened, throws a half-moon light. His plastic tent-like costumes, once shed, float up into a mobile cluster.

Feldman’s score for a searing soprano solo and orchestra carry this impressive work. It feels nightmarish, with two of the dancers, Cynthia Koppe at first, and later, less frantically, Zak Ryan Schlegel, trapped in spasm, their long, loose hair and limbs flaying. Koppe squirms in a repetitive cycle on the floor while the others slowly march past. A man gives Koppe a hand to pull her up, then pulls her slowly away and into the light.

Vortex Temporum - October 15, 2016

Dance & Music: Rosas & Ictus / Choreography: Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker

Left to Right: Cynthia Loemij, Marie Goudot, Boštjan Antončič, Michaël Pomero, Julien Monty, and Igor Shyshko in Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker's Vortex Temporum

Photo: Robert Altman

Large, white circles interlock on a stage which is bare except for a grand piano. Six musicians scurry downstage and pause, their black-clad look sparked by the silver stilettos worn by flutist, Chryssi Dimitriou. They play, with savage attack, the mesmerizing

Vortex Temporum, composed by Gerard Grisey, a Frenchman who died at age 52, two years after

Vortex premiered in 1998. Dirk Descheemaeker, the pianist makes his sound soar. Imagine a repetitive minimalism, somewhat like Steve Reich (which

Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, conquered with her

Fase) combined with a textural, dynamic complexity.

Expecting a dance, we imagine one in the absence of physical dancers. Then, the musicians exit. Five men and two women, black shirts hanging over black pants, rush in to inhabit the same space. They sag; the air still charged with Vortex. Their sneakers squeak with each sharp pivot. The pianist returns to accompany a high-stepping solo of Carlos Garbin. With that, the musicians and dancers begin their vortex, intermingling, the piano pushed to circle throughout the space. We are invited to listen and gaze, and question de Keersmaeker’s attempt to match Grisey’s ingenuity.

Letter to A Man - October 20, 2016

Based on the diary of Vaslav Nijinsky; Text by Christian Dumais-Lvowski

Direction, set design, and lighting concept by Robert Wilson & Mikhail Baryshnikov / Music by Hal Wilner

Mikhail Baryshnikov in Letters to a Man; Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The unforgettable face of

Vaslav Nijinsky hangs in a frame center stage as the audience files into the BAM Harvey. Jaunty music and yellow footlights wrestle with our reflection on the Russian genius known as the “clown of God,” the lover of

Serge Diaghilev, the choreographer whose instincts bridled convention.

Blackout.

Though we don’t know it at the time, thus concluded our one straightforward encounter with Nijinsky.

The equally irresistible face of Mikhail Baryshnikov appears in a narrow, vertical column of light, the first of a stream of stunning moments charged by luminance. The lighting designed by long-time collaborator A. J Weissbard is arguably the star of this production that centers around an artist’s lonely efforts to distinguish himself from God, to understand war, and to love -- while not caring for lust. Robert Wilson offers us a feast of theatrical ideas: recorded narration repeated in both English and Russian, with projected supertitles and graphics; props such as a burning cross, large flowers, flying and stuffed swans; and mood swings, from intense to insouciant. Baryshnikov is his arresting self, particularly when he stands as though captured by a spirit.

Precise, sharp, still or gamboling, Baryshnikov fleetingly resembles Joel Grey in Cabaret mode as he channels Nijinsky.

The Dance Enthusiast:Sharing Reviews/Impressions and Creating Conversations.

For more Impressions of Dance on The Dance Enthusiast

Share your #Audience Review of these shows or others for a chance to win a Foodies delight, Gourmet Olive Oil