IMPRESSIONS: Reggie Wilson/Fist and Heel Performance Group in "The Reclamation"

Choreographer: Reggie Wilson

Lighting Designer: Tim Cryan

Associate Lighting Designer: Betsy Chester

Costume Designers: Naoko Nagata and Enver Chakartash

Music: Son House, Gladys Knight & The Pips, Ali Farka Touré, Tom Smothers, Ngqoko Women’s Ensemble, Lulu Masilela, Ethel Perkins, Rosalie Hill, One String, Fist and Heel Performance Group, Staple Singers

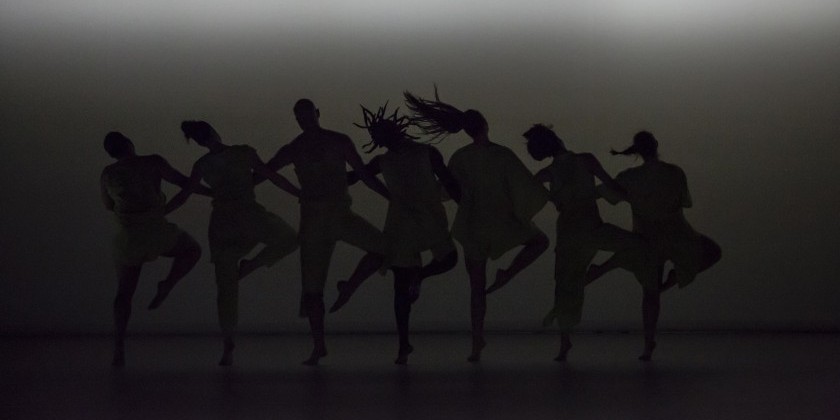

Dancers: Oluwadamilare (Dare) Ayorinde, Bria Bacon, Paul Hamilton, Rochelle Jamila, Annie Wang, Henry Winslow, Miles Yeung

Venue: NYU Skirball

Dates: April 4 - 5, 2025

I admit, it was the motivating theme behind choreographer Reggie Wilson’s new work, The Reclamation, that attracted me. Captivatingly performed by his Brooklyn-based company, Reggie Wilson/Fist and Heel Performance Group, the work premiered at NYU Skirball in early April. According to program notes, the 60-minute ensemble piece for seven dancers is inspired by Wilson’s desire to re-claim foundational ideas from his early work and discover how, or if, they continue to resonate today. Such re-examination of one’s past experience and concerns over what, if any, of it maintains contemporary relevance, hold pertinence, I suspect, for anyone of “a certain age.”

Since the founding of his troupe in 1989, Wilson has been merging post-modern choreographic approaches with cultural knowledge derived from the experience and traditions of Africans in the Americas. Based on research he conducted in the Mississippi Delta, the Caribbean islands, and Africa, Wilson has made dances over the years in a self-created style he terms “post-African/Neo-HooDoo Modern.” And The Reclamation is no exception.

One may be tempted to sit back and take in the work’s uneasy juxtapositions of African-American vernacular music and stark post-modern dance phrases from a purely aesthetic perspective, titillated, perhaps, by the foreboding, darkly unsettled mood the mixture elicits. But in today’s dangerously divided political climate, it feels negligent to not acknowledge the fraught relationships Wilson’s latest piece calls to mind between the history of African-American lives and the forces driving contemporary “choreography,” be it of movers on theatrical stages or players in larger societal arenas.

The piece opens with an announcement: “’Motherless Children,’ take two.” We immediately wonder, does that mean us, under Trump 2.0? To strains of a Son House recording of the gospel blues classic, each dancer takes a moment to walk to the edge of the stage and stare out into the distance, and into themselves. Skillfully shifting between external and internal focus, the performers turn their ritualistic “parade” into an apt kick-off for the work’s abstract portrayal of disconnection, among and within individual souls.

The soundtrack changes to Gladys Knight & the Pips singing the sunny lyrics of “I Can See Clearly Now.” The dancers line up and walk toward us, taking only one forward step, and then rocking backward before stepping forward again. Their movements are plain, sad, and unaffected by the cheeriness of the music. The song’s insistent claims of “a bright shiny day” defy what we see. We feel assaulted by the pretense.

Proceeding episodically, the work comprises discrete sections dictated by its emotionally charged selections of folk or popular music drawn from African diasporic sources. The riveting score ranges from raw, twangy, and wailing to propulsively rhythmic, slick, and satiric. Yet the formalistic, deliberately executed choreography changes only minimally as the piece progresses. While the dancing may grow in intensity, it remains rooted in a movement lexicon that repeats rather than evolves. It’s Cunningham-esque in its angularity, bold body shapes, affinity for geometric patterns, and detached performance style. We also see tiny adorning gestures (like wiggling hands), forceful kicks that drop heavily to the ground, and moments of looseness that mark the choreography as uniquely Wilson’s and can be read as instances of connectivity, when the dance seems momentarily touched by the musical sounds.

For the most part, the dancers move independently, in their own spatial bubbles. Only from time to time does an individual approach another dancer, touch or support them in some way, and then move on. One is reminded of the belief that, while we’re essentially alone, when you really need help, someone will arrive to provide it.

By the end, however, we’re left with the image of singular bodies dancing doggedly in their own fashions, oblivious to the stylish sound and insistent pleas of the Staple Singers asking us to “Touch a Hand, Make a Friend.” When the smart music stops, the dancers drop to the floor and roll together in a circle that feels so basic, so needy, so tribal — and all the lights go out.

On April 26, Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery will screen GROUNDS THAT SHOUT!...and others merely shaking, a documentary involving Philadelphia-based choreographers responding to the layered histories of race and religion in three of the city’s historic churches. Sparked by similar historical research he did at St. Mark’s in 2018, the documentary was curated by Wilson. The showing will feature a conversation with Wilson, and while I don’t know if the documentary is any good (the venue could not provide me with a screener to view in advance), it will surely be rewarding to hear Wilson speak about the underpinnings of his always-deeply-researched work.