IMPRESSIONS: Catherine Gallant/DANCE in "Escape from the House of Mercy" at University Settlement

Catherine Gallant/DANCE

At The Performance Project @ University Settlement, 184 Eldridge Street, New York City

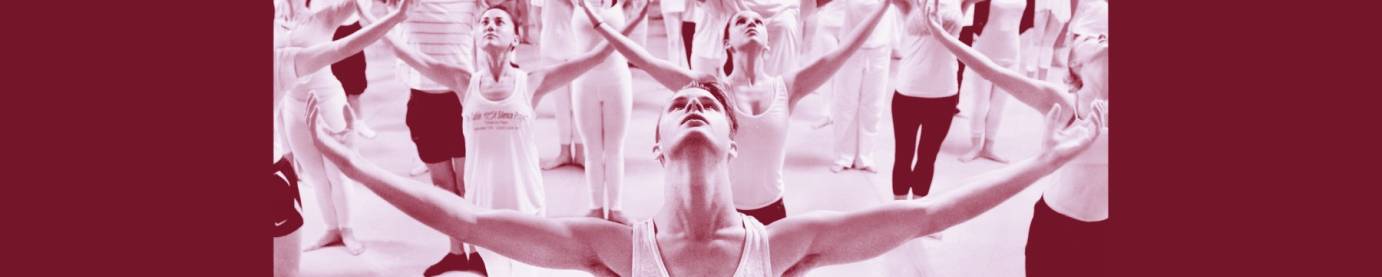

Performers: Anne Parichon-Buoncore, Kelli Chapman, Halley Gerstel, Charlotte Hendrickson, Jessie King, Erica Lessner. Megan Minturn, Jasmine Oton, Cecly Placenti

Choreography: Catherine Gallant in collaboration with the performers

Recorded music composed and performed by Dana Lyn and Kyle Sanna for the dance film STONES/Whispers from the Workhouse

March 22, 2025

Catherine Gallant’s new production of Escape from the House of Mercy could not have been better timed. With a new US government that openly reviles immigrants and boasts about denying them due process of law, Gallant gives us a historic precedent, a horror show from the past. Though flawed as a theatre piece, it does make the essential point — that freedom in America is not for everyone.

The House of Mercy was a real place, a “workhouse” in Inwood at the northern tip of Manhattan, where pregnant, abandoned, or unwanted women and girls “disappeared” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many were Irish immigrants. They wound up toiling like prisoners, washing the clothes of respectable New Yorkers, serving indefinite sentences that could go on for years,

A cast of nine women does a credible job of portraying the misery of these inmates. We see them wrangling the white shirts of the rich, teasing and tormenting each other out of frustration, and restraining each others’ vain attempts to break loose. Their diminished existence is represented by shrouds of tulle that cut them off from pleasure and play, and from each other. This fabric is balled up and used to represent the output of their labor — both the laundry, and the children they bear. Some of the most effective choreography comes in the birth scenes, where babies are pulled out and taken away — and in a fantastic depiction of servitude, where inmates are used as tea trays, balancing cups and saucers on their backs, heads and upturned feet.

They sit in a circle and curse their fate — calling the House of Mercy a house of guilt, a house of lies, a house infested with desire. All those lines raise dramatic expectations, but none is followed up. Despite the promise of the title, no one escapes from the House of Mercy (even though historical accounts indicate that some did.) The inmates are just as miserable in the end as at the beginning. Nothing happens but this endless cycle of wash, work and woe. Worse, we learn nothing about who was responsible for such injustice — not a hint in the dance, the images projected on the rear wall, or even in the program notes. The city, the church, police and families were all complicit, we can assume. But assumptions are not dance drama.

In fact, historical records show the Inwood House of Mercy was a mission of the Episcopal Church, run by an order of Episcopal nuns who became notorious for their harsh methods of supposed rehabilitation. In the 1890s, court papers accused the institution of cruel and unusual punishments, including “locking inmates in a small room or cell without food or water for (up to) five days… corporal infliction by whipping, the use of a gag, handcuffs and a straight jacket.” After many such complaints, the house was taken over in 1921 by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Halley Gerstel stood out in the cast — looking gaunt and emotionally exhausted, expressing her despair in a silent scream. She made you think about the horrors faced by immigrants now being rounded up by ICE and forced into prison labor in places like El Salvador. With history repeating itself in cruel and unusual ways, this show needs to do more justice to its subject matter.