THE DANCE ENTHUSIAST ASKS: Stephen Petronio’s Final Bow (For Now)

Stephen Petronio on Sunsetting his Company and What Comes Next

After four decades of groundbreaking work in contemporary dance, Stephen Petronio is preparing to close a major chapter of his artistic journey. With the upcoming final season of the Stephen Petronio Company, culminating in performances at Jacob’s Pillow, Petronio reflects on his decision to sunset the company, his artistic evolution, and what comes next. In conversation with The Dance Enthusiast’s Theo Boguszewski, he speaks candidly about the shifting landscape of dance, the impact of his Bloodlines Initiative, and the importance of preserving the postmodern dance lineage while fostering the next generation of artists.

Theo Boguszewski for The Dance Enthusiast: We’re here to talk to you about your legacy and your decision to sunset the Stephen Petronio Company. After 40 years of making work, what led you to this decision?

Stephen Petronio: Well, 40 years of making work! Ha. Let's see… I’ll give you a little bit of the evolution of the company. We started in the ‘80s; there was a giant dance boom going on, and the company was very focused on the creation and production and dissemination of my work. And my work entailed interdisciplinary collaboration with visual artists and musicians and fashion designers; the breadth of my collaborators is very exciting to me and I'm very grateful. But then at a certain point, probably when I hit 25 or 30 years, a switch flipped and I decided that it didn't all have to be about me.

I have a unique movement style, but what I've made is built on the bones and in the minds of so many other artists. And so I wanted to really pay homage to the predecessors that inspired me. So I devised this project called Bloodlines. When I was a young dancer I was very lucky to meet the Judson artists; I came in at the right time and I met Steve Paxton when he was just creating contact improvisation, and he introduced me to Trisha Brown. And Trisha introduced me to Yvonne Rainer. And I was taking classes at the Cunningham Studio. And Lucinda Childs lived downstairs from Trisha and David Gordon. It was a very rich time in the dance world. And I was a young, hungry, arrogant guy.

I started to feel like I was watching that generation recede and I wanted to pay homage to them. And I thought, wow, instead of just thinking about me, I could think about my predecessors and bring them onto my stage. So it was an interesting frame for my work; maybe presumptuous, but that’s what I felt like doing. And then I realized that, okay, well, I'm in a continuum. It's like a stream or a river. And there's the next generation coming after me. So I made Bloodlines(future). And it was super exciting.

Then I began to think about, “well, what's really important to me?” I had watched Merce and Trisha touring the world until they were in their 80s and 90s. And it just didn't seem like that was possible for me. And so we founded the Petronio Residency Center. I thought that would be a way to lay roots into a community and also to give space to young choreographers for research and development in the middle of a pristine environment. An arts organization, taking on the mission of environmental responsibility. We ended up preserving 77 acres. It’s forever wild – it will never change.

And although the Residency Center closed after seven years, mostly because of lack of funding, that 77 acre parcel of land which attaches to the Catskill Reserve will be there forever. I'm very proud of that. I mean, I've made a few good dances that I'm proud of, but I'm really proud of the fact that the StephenPetronio Company, with the help of Doris Duke, merged the idea of art and environment in a way that most people still don't really understand.

I just thought it would go on forever. I thought I would spend my twilight years at that Retreat Center. But then the pandemic hit and funding priorities shifted and the world had something different in store for me. Although the property was paid for, I couldn't raise enough money to continue to program it.

And then there's touring — I was also supporting this thing with touring, and touring really slowed down for me. My work has been wildly popular over the years, and it's not at this moment. So it just seemed like all the streams of income were drying up at once. I accrued a lot of debt during the pandemic because I thought, well, I'll just keep borrowing money to support the company and artists at the residency, and I'm good at raising it. But when on the other side of the pandemic, the world had shifted, and it just felt insurmountable. We had gone into a very negative cash flow place and I didn't have anywhere else to turn. So we sold the property. And I've made peace with that.

Did you feel that the tapering out of touring was related to the pandemic?

Hard to say. I'm in my 60s. I've been doing it for a long time. But I think what happened was the touring circuit really shrank, and I was maybe the wrong artist at the right time. I've been on top of the mountain for a long time and so things have to shift. So I stepped back and thought, okay, let's look at what the next generation is doing.

After this big milestone, what comes next for you artistically?

We do have a final season. We have a 16-week rehearsal period where I'm bringing back a lot of the works that I love. And then we'll take some of those works to Jacob's Pillow, for It Ends Like This. And we've created a fund for young artists to the tune of four or five hundred thousand dollars. So there'll be gifts to young artists going into the future after my company closes.

The Stephen Petronio Company has really always been focused on live performance; I'm very old fashioned in that way. I really believed in the dusty dirty theater, and what I do in three dimensional space. But we are going to be looking more at film, and we'll be licensing the work. We're building an archive so that people can access the work in the future.

I've been making one or two works every year for 40 years; I expect that I'll be making more work. It’s not like that thing turns off.

Can you share more about Bloodlines(future)? What are the logistics of how it operates, and how do you select people for awards?

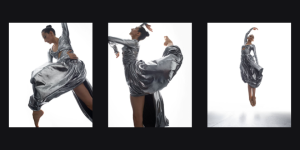

So, Bloodlines(future) really was operating alongside the Residency Center and the Stephen Petronio Company. I did a lot of work with Danspace, we did a number of collaborations together where we split residencies and that kind of evolved into the Bloodlines(future) platform. And I would just pick somebody each year that I thought was interesting. I met a guy named Johnnie Cruise Mercer — I loved him since the minute I saw him. We ended up making a duet together for American Dance Festival, which was very unexpected. To have a man in his 60s dancing next to this wild, beautiful 20-something-year-old, that's very surprising to me.

When I saw Johnnie, I knew immediately that I was watching him pull movement out of the air in a way that I understood. And so that was an easy one. There are some artists in Bloodlines(future) that I don't understand, but I can still smell something really exciting. Yeah, like Malcolm-x Betts. I don't know what the hell he's doing, but it's so compelling. So that's the beauty of being around these young artists; they’re at the beginning of their arc, there's a hunger that is so exciting to me.

Let's talk a little bit about It Ends Like This, your farewell program this summer at Jacob's Pillow. How did you choose the specific pieces that you’ll be presenting?

It's been an interesting and difficult selection process. There are four curators at Jacob's Pillow, all women. And they got me on a zoom and were very, very kind to me. It was a dark moment, everything was kind of faltering. And they said, “We would like to do your last show.” It was a beautiful gesture, and I'm very grateful to them.

And then I had a good six months to think about it. And of course, it was torturing me because how do I pick the last things we're going to do? In the end, I got it down to two different programs, and I brought it to the curators, and they were like, “we think it's better for the audience to have one program.” Then I had to cut it in half. It was an editing process.

So here's what I decided to do: over the 16 weeks leading up to Jacob's Pillow, the last Thursday of every month, we're going to open the studio to a free class for the community. And then we're going to show a rehearsal/ workshop version of a piece that's not going to be at Jacob's Pillow. Some of my other favorites will get shown in New York on those Thursdays. It’ll be very informal, in the studio, no admission or anything like that. Then we get to Jacob's Pillow.

I selected a solo of mine called Broken Man that I made in 2002. I made it after 9/11. And I can't do it anymore, but I'm very interested in passing that on to a younger dancer. So I'll teach it to all of the dancers and see what happens. And maybe it'll be done by a different person each night, or maybe one or two people. We'll see how it goes.

Then, how could I have a closing program without MiddleSexGorge? So MiddleSexGorge is a piece I made in 1990 while I was a member of ACT UP, while the AIDS crisis was going on. And I was getting arrested and engaging in civil disobedience, and I was trying to figure out a way to make something with my body that felt as important as those civil disobediences were on the street with ACT UP. It was costumed by H. Petal. I am H. Petal. I've been designing under that pseudonym for my entire career and you're the first to hear it. You know, I’ve found that in New York, people don't want you to be good at more than one thing. So I just made another name.

Am I allowed to share that with The Dance Enthusiast audience?

Yes, of course, I’m telling you now.The costumes for MiddleSexGorge are important to me because the men are in pink foundation corset wear, and their derrieres are exposed. The women are wearing black, much more functional. So there's a reversal. Of course, back in those days, gender was pretty binary. Although I called it “Middlesex”; I was reaching for a sex in the middle. So we're doing that piece, which I'm very proud of. And that's the first half of the program.

For the second half of the program, I've got a new solo that I've been working on this year for a body of my age where I'm talking and dancing and that's called Another Kind of Steve. And I'll be talking about my relationship to Steve Paxton and Trisha Brown. And the last piece is American Landscapes, in collaboration with the amazing artist Robert Longo, who's a contemporary of mine. And the music is Jozef Van Wissem and Jim Jarmusch. And of course, Ken Tabachnik lights everything for me the whole evening. After Hillary lost the election, I could only make the most abstract work, because I couldn't respond. And then the following year, I made American Landscapes where I was beginning to point at things that I felt smelled like the America of the moment.

So I'm just going to say — this is not the final statement. I'm just opening the journal at a couple different chapters that I'm very fond of.

What’s the significance of having Jacob’s Pillow as the venue for your last show?

Well, Jacob’s Pillow, it’s just such a historical dance platform in America. It’s Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis. When Ted Shawn selected his Men Dancers, he was doing what I began to subconsciously emulate with my retreat, putting dancers in the country.

When I was climbing the ranks, from being a young dancer with Trisha Brown to being a choreographer, one of my first engagements with Trisha Brown was on that stage. And then I was invited with my company to be on the outdoor stage, for Inside/ Out. So I did a couple of seasons of that, and then I graduated into the Ted Shawn Theater, and I did a number of seasons there. I've spent a lot of time at Jacob’s Pillow. I love it.

How do you feel that your choreography has evolved over the years and what do you think has remained a constant in your artistic voice?

Excellent question. I'm extremely restless. I'm interested in punctuation. I'm not that interested in modulation. I tell this story a lot. I was in an improvisation class very early on, and my teacher, Danny Lepkoff, said to me, “Stephen, you're like a faucet. You get turned on and it comes rushing out, and then you just turn off and there's nothing.” And I went home that night and I thought, that is what I'm going to build my vocabulary on, that lack of modulation.

And also, the hyper speed. When I was younger, I was going to see Balanchine a lot, and at the time that work was insanely fast. And then in the 80s, it was beats per minute: how many beats per minute could you put in the music and still not explode?

One of the places where I believe my contribution lies: my work was very much about merging the softer somatic techniques of spherical flowing energy with the extended striking out in space of classical work. In some ways, that's the hallmark of my language. Everybody understands that now, but that was very new in 1980. And you know, it has been very important to me to push the tailbone and the pubic bone forward into the audience's face. I really nailed that in MiddleSexGorge. That first chakra was, like, taboo back in those days; everything was very minimal. I felt like my generation had permission to really shove that forward. I have built a language that has those ideas in it. I try not to illustrate, I try to embody.

What has been the influence of your predecessors, and specifically those Judson Church greats?

Well, an infectious interest in discovery. They were also super formal. They wouldn't talk about sex, for example. They wouldn’t talk about issues, they would talk about measurements, you know, like “the sleeve is a three quarter sleeve and the space is a grid.” They talked about things that weren't emotional, in order to create emotion. And I really love that formality. It's very much inside of me. But I also am a child of the 80s so I love to talk about dirty things or provocative things or intellectual things or mundane things. I'm not afraid of pop culture.

When I was coming up, it was very much, “oh, you’re either a high artist or a low artist”. And “oh, if you bring sex in, then you're like every other entertainer.” And I didn't really give a crap. I come up from a lower middle class Italian background. I didn't really care about the rules. They didn't fit me anyway. I've been brave enough and stupid enough to do whatever I want. I take it on the chin when I get hit on the chin and I'll bow if you clap.

Do you feel like your decision about how to go about sunsetting your company was in any way in response to, for example, watching Merce and what Merce did, or watching what Trisha did?

Absolutely, 100%. First of all, watching Merce pass and then watching Trisha get sick, I mean, I was there. I always used them as a guide of what was possible. And watching them travel around the world in their 80s, you know, sometimes stumbling, sometimes needing to be helped, sacrificing their personal life, using a lot of jet fuel…

And there was an assumption that I was going to want that. You know, if you're going to succeed, you have to have that big organization and keep it going until you're dead. And I started Bloodlines because I didn't think that model was relevant to me. And then the other thing is, I just didn't want to end up in a train station in Barcelona not knowing where I was, that's not what I wanted for myself.

And the environmental movement really began to kick in around that period and I began to see the possibility of making a place that is much more sustainable environmentally, not jumping on a plane to tour. My measure of success as a young artist was how much I traveled, how many miles, how many different french fries I ate in how many different cities, how many museums I saw, you know like, go, go, go, go, go. Collecting that like a badge. And it was exciting, but the world is hurting.

Obviously this is a very challenging moment for the arts and a very challenging moment for our country. As you are contemplating this transition, is there anything that you feel you can do in response to that?

Oh, you're gonna make me start crying. We're in a very dark period, and I feel so much for the young artists. All I can say is, you’d better show us the way, because this country's in trouble. I'm very emotional about this. We need this new generation to fight like hell. You know, there were a lot of systems set up in place for me to succeed.

I just hope this generation can find the cracks and the crevices to keep making their work. Maybe it's not going to get the kind of opera house treatment that one might expect success equals. But we NEED dance. Part of the reason I love dance is because, if I can make an idea with my body, I've succeeded. I just really encourage people not to abandon their bodies, and to find the cracks where no one's looking, and put something radical there.