IMPRESSIONS: Carolyn Dorfman Dance in "The Legacy Project: A Dance of Hope"

Choreography: Carolyn Dorfman

Music: Greg Wall, Bente Kahan, Ilse Weber, Imre Kalman, Karel Svenk, Jessie Reagen

Text: Ilse Weber, Leo Strauss, Karel Svenk

Dancers: Kayleigh Bowen, Tyler Choquette, Dominique Dobransky, Hannah Gross, Maiko Harada, Brandon Jones, Jacob Kurihara, Aanyse Pettiford-Chandler, Charles Scheland, Jared Stern

Dates: January 11-12, 2025

New Jersey-based choreographer Carolyn Dorfman, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, is a master craftswoman when it comes to composing modern dances that specifically reflect the Jewish experience, yet trigger elemental emotions that resonate with all of us.

In a touching, sometimes tear-inducing performance of The Legacy Project: A Dance of Hope at New York’s 92nd Street Y, her 10-member, multi-ethnic company, Carolyn Dorfman Dance, gave passionate interpretation to excerpts from Dorfman’s two-part Mayne Mentshn (2000/2001), a celebration of her Eastern European Jewish heritage and an American immigrant story.

Sandwiched between the parts, the company proffered Cat’s Cradle (2007), Dorfman’s episodic, highly theatrical modern-dance piece inspired by Voices from Theresienstadt, a musical (by Ellen Foyn Bruun and Bente Kahan) featuring heart-rending text written by prisoners in the titular ghetto in Czechoslovakia, a famous Nazi “holding ground” for those awaiting deportation to killing centers.

What’s most impressive about Dorfman’s choreography is its expressive clarity and simplicity. There’s no “filler” dancing, just clear, shrewdly-chosen, often symbolic, gestural movements that speak with powerful dramatic effect. In “My Father’s Solo,” the opening segment of Mayne Mentshn (which means “My People” in Yiddish), the dancer’s hunched shoulders, lifted pulsating hands, and repeated reaches, falls to the floor, and rising “wipe yourself off” actions express, in a matter of seconds, the “who, what, and why” of this old Jewish man. When the character returns at the end of the show, and we see his signature hand gesture evolve into shoulder-blade impelled arm lifts that permeate an entire ensemble of “immigrants,” one appreciates the tight crafting of Dorfman’s choreography, how cleverly she ties everything together, always tethering singular movement ideas to the larger story-telling content.

Because of how character-driven and narrative-evoking it can be, Dorfman’s choreography sometimes feels like theatre-dance. However, her use of the body is so expansive — a hand gesture is never just an isolation, but includes the way the spine tilts in response to it, the feet plant to ground it, the facial expression it sparks, and the intensity of energy used to generate it — that her work sits indisputably within the realm of concert dance and never feels reductively literal.

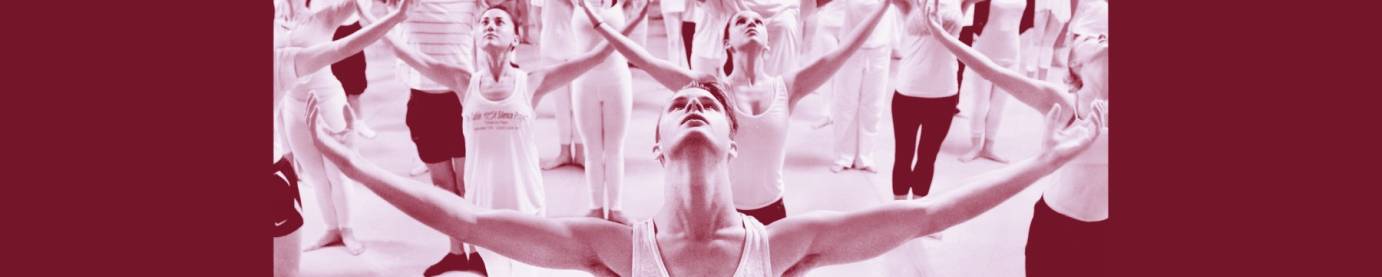

While prioritizing the expression of human experience, Dorfman’s work is also enthralling from a purely visual perspective. She is expert at incorporating unpredictable level changes into solo dancing, devising eye-catching group-movement patterns, and designing striking, unusually-balanced individual body shapes and tableaux — in an episode about the children’s ward at Theresienstadt, a deep diagonal line pierces through a collective of fearfully embracing curved bodies and we feel the youngsters’ hurt with unbearable sharpness.

Dorfman also makes ingenious use of props. Cat’s Cradle opens with a trio of women forming a tight circle, their bodies interwoven, tipped heads braced against one another, and each holding a ball of yarn. Ultimately, they stretch and move apart while keeping hold of their yarn which, in the piece’s final section, unwinds to attach to a pile of lifeless bodies and configures in a way that shows the women’s continued connection to one another and to their haunting memories. In one of the warm, revelatory speeches Dorfman inserts throughout the show, we learn that her mother and two aunts survived the war because they could knit.

We also learn that the pain of hearing about the Holocaust from her parents while growing up was the “single most defining” aspect of her life. In introducing her show’s closing segment, (the second part of Mayne Mentshn, “The American Dream”), she tells us she wants to communicate the “uniqueness of the Jewish immigrant experience as well as its applicability to all immigrants.” Musical theatre fans will surely be reminded of how beloved the extraordinarily successful Fiddler on the Roof remains, for this very reason.

Dorfman’s American-immigrant choreography is immeasurably enhanced by its jazz-inflected, commissioned score by Greg Wall. The “happy” swing music that accompanies newly-arrived immigrants — the dancers trying to season their modern vocabulary with Jack Cole-flavored jazz sensibilities — turns darker and more complicated in affecting reflection of the pain and anger of an excluded immigrant fighting to belong, then wrestling to merge his cultural past into his new, unknown future. Bravo to dancer Jacob Kurihara for his performance in this role!

And kudos, also, to the entire cast. Their pleasing, polished dancing of the work of this important choreographer brought joy, tears, understanding, and hope.