IMPRESSIONS: "Edges of Ailey" at The Whitney Museum of American Art

Edges of Ailey at The Whitney Museum of American Art

Open September 25, 2024 to February 9, 2025

Curated, and with a catalog edited by Adrienne Edwards, Engell Speyer Family Senior Curator

and Associate Director of Curatorial Programs

“Dance is for everybody. I believe that the dance came from the people and that it should

always be delivered back to the people." — Alvin Ailey

Activist, dancer, and choreographer, Alvin Ailey stands at the fulcrum of the Whitney Museum’s Edges of Ailey exhibition running through February 9, 2025. Divided into sections that flow from one area to the next, the exhibit offers a confluence of Black choreography, art, and music that Ailey created or that influenced Ailey or was tangentially part of Ailey’s world. Its themes are the American South, Black spirituality, Black women, Black music, and Blackness in dance. It charts a timeline from the Civil War to the segregated Jim Crow south, to Black Liberation, and to the present-day plight of Black Americans. Ailey’s commentary on being Black and marginalized is noted in his journal entries, viewed in interviews, and expressed in his dances. Ailey was gay, but his gayness is primarily revealed in the journals that he kept from an early age. He succumbed to AIDS-related complications on December 1, 1989.

Edges of Ailey was six years in the making. Curator Adrienne Edwards has assembled archival material, numerous artworks, and an extensive catalogue, and has commissioned performances by 10 choreographers. The entire 18,000 square-foot 5th floor is given over to this large-scale exhibit. Performances take place in the theater on the 3rd floor. Free dance classes, talks, music, drawing workshops and tours are offered. Scott Rothkopf, the museum’s director, calls Edges of Ailey, “the most ambitious and complex exhibition undertaken in the Whitney’s history.”

Museums present dance, but major institutional shows revolving around one choreographer are rare. This show attests to Ailey’s far-reaching influence as a cultural icon. As a leader, he inspired loyalty. Together with his dancers, friends, and supporters, he built both a cultural haven and a dance empire. Ailey’s company, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) continues to thrive. Its permanent home in New York City, which also houses Ailey II, The Ailey School, Ailey Arts in Education & Community Programs, and Ailey Extension, is the U.S.A.’s largest building complex dedicated to dance. Its second home, in Kansas City, MO, has energized that community since 1968.

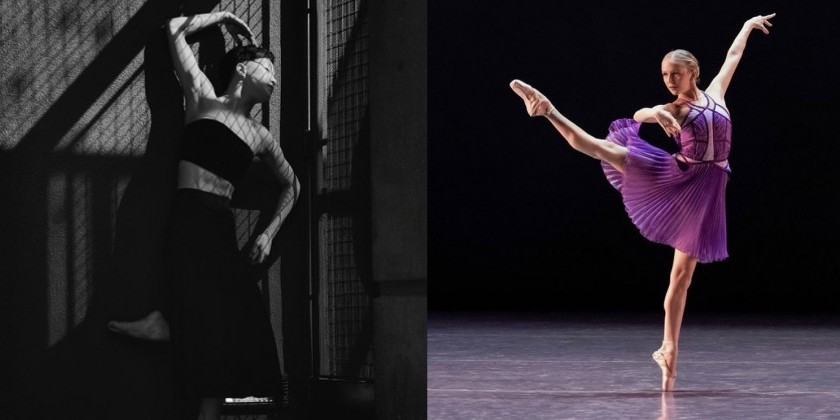

Photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024

The exhibition space is painted blood red, recalling Ailey’s “blood memories” from his life as a boy during the Depression in rural Texas where he was born on January 5, 1931. “I’m a Black man whose roots are in the sun and the dirt of the South,” Ailey said. Attending the Baptist church, listening to the blues, picking cotton, enduring segregation, and watching adults as they danced (when he snuck out at night) are explored in his choreography.

Ailey choreographed his magnum opus, Revelations (1960), when he was 29 years old. This dance, which reflects the experiences of his boyhood, has been viewed by 23 million people in 71 countries, and is “the most widely seen modern dance work in the world." (Ailey website) It finds its way onto nearly every Ailey program. The dance summarizes the universal desire for freedom, redemption, and transcendence, and offers hope for a better future. It holds a persuasive message for humanity.

Ailey’s other 80 dances did not reach this early, high, and promising bar. They were compared, and not necessarily favorably, with this fledgling success. To bolster his own repertory, he welcomed the choreography of younger Black and white choreographers making AAADT one of the first modern dance repertory companies with an established choreographer at its head.

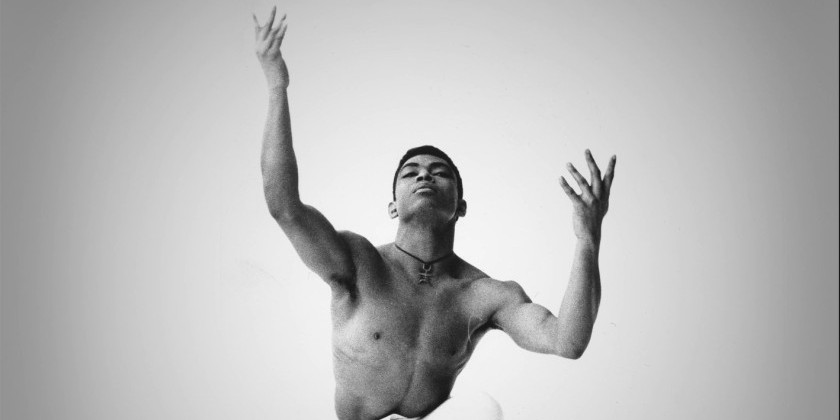

The first time I attended Edges of Ailey, I spent hours looking at the video monitors screening the work of Lester Horton, Martha Graham, Jack Cole, Pearl Primus and Katherine Dunham, with whom Ailey danced or studied, and who influenced him. It was fascinating to compare their choreography and to watch a young Ailey perform. Carmen de Lavallade, Ailey’s closest friend and dancing partner, remarked that Ailey was an “awkward dancer,” but he was beautiful-looking, approachable, and charismatic. He danced with desire and need. In video I viewed, Ailey developed fluidity. Ailey was an omnivore who explored all the arts. He studied ballet, modern, and jazz, and amalgamated them in his choreography. “I wanted to paint. I wanted to sculpt. I wrote poetry. I wanted to write the great American novel,” he said. Eventually, his art became “movements full of images.”

© Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

In an exemplary Horton dance from the 1950s , Ailey appears in a straw hat with the lovely de Lavallade in a prairie dress, circling one another and performing contractions on the floor. Playbills and commentary were also part of this section. Stella Adler, Ailey's acting coach, said, “Don’t be in the middle,” regarding an actor’s character. The New Dance Group, a gathering place for both Black and white dancers, in which Ailey participated, proclaims on their recital poster, “The Dance Is A Weapon.” The young Ailey took these edicts to heart.

Ailey danced in four productions on Broadway while founding his company in 1958. Reflecting Ailey’s view of inclusivity, the company, courageously, became multiracial in 1962, when the fight for and against segregation was in full fury. A particularly harrowing incident took place in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Black Americans, many of whom were children, participated in a nonviolent march against racial segregation, and were attacked on a bridge with clubs, fire hoses, and dogs by the Birmingham police.

Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody. © Lonnie Holley

A looped video frieze running around the top of the space, like a ribbon encircling and blessing the exhibition, features performances of Ailey’s dances and his musings. The videos feature a tall woman soloist, Consuelo Atlas promenading in arabesque to Laura Nyro's song, December Boudoir, and women dancers in slinky, red, off-the-shoulder gowns, white wigs, and high heels sashaying to Nyro’s Stone Cold Picnic, which is the opening of Quintet. In interviews, Ailey says, “we celebrate the human being,” we are giving “opportunities to young people in dance,” and “my dances reflect what goes on in this country and I can’t help that.”

The space below the frieze is filled with works by celebrated artists who comment on the hardship and subjugation of Black Americans, as well as portray Black people just going about their business. Kara Walker’s African American, a silhouette of a Black person dressed in ‘native’ garb, and Birmingham, Alabama-born, Lonnie Holley’s Sharing the Struggle (2018), in which two distressed wood rocking chairs are wrapped in fire hoses, exemplify the fight for equality. Stereotypical Blackness in the white world of Hollywood is commented upon in Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Hollywood Africans (1983). Watts Tower builder Noah Purifoy’s found object construction, a stolid African-looking deity, reminds the viewer of ancestral heritage. Street Life Harlem (1939-40), by William H. Johnson, depicts a man and a woman out on the town in colorful garb. Portraitist Barkley Hendricks paints a contemplative woman dancer in a white leotard, and a poignant, seated portrait of an attenuated de Lavallade was painted by Geoffrey Holder, her celebrated husband and a rival of Ailey’s.

Courtesy James Fuentes Gallery

Said Ailey, “Look how beautiful we are, look how wonderful we are as Black people. Look what’s happened to us all these years despite our problems, despite our being brought here as slaves, look what has grown in us.” Ailey, as this exhibition aptly epitomizes, was the center of a dance movement that affected the direction of American culture.

© Lorna Simpson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth