IMPRESSIONS: Soledad Barrio & Noche Flamenca at The Joyce Theater

Searching for Goya

The Joyce Theater Foundation presents Soledad Barrio & Noche Flamenca

April 23 - 28, 2024

Martín Santangelo, Director and Choreographer, presents Searching for Goya

Featuring: Soledad Barrio and Pablo Fraile, Jesús Helmo, Paula Bolaños, Salva de María, Manuel Gago, Emilio Florido, Salva Cortés, Stella Goldin García, Alexa Ratini, Alishanee Chafe-Hearmon and Dimitrios Bournias

In Searching for Goya at The Joyce Theater, Soledad Barrio & Noche Flamenca, the longstanding flamenco company based in New York City, presents a compendium of dances predicated on the images of 18th-century Spanish artist Francisco Goya. The dances, by choreographer Martín Santangelo, embody the spirit of the paintings. Lauded soloists, including the company’s namesake, are featured in this nearly two-hour production. The formality of the dances provides a backdrop for fierce and emphatic solos.

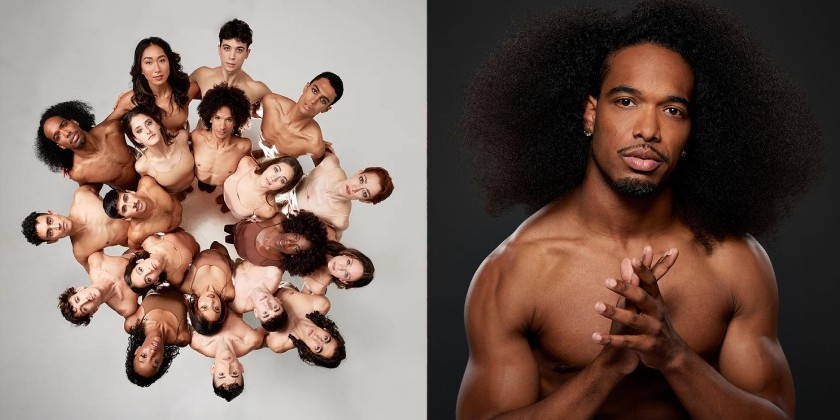

(L to R top) Alishanee Chafe-Hearmon, Emilio Florido, Jesús Helmo, Marina Elana, Alexa Ratini, (L to R bottom) Soledad Barrio and Pablo Fraile in El Sueño de la Razón Produce Monstruos. Photo by Kaji

The opening tableau features a man wearing sunglasses and slumped over a table as in the etching El Sueño de la Razón Produce Monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters). Surrounded by kneeling dancers in trench coats and others who hold aloft large, black-feathered fans resembling ‘night creatures,’ the man (singer Manuel Gago) looks up and strikes a distinctive rhythm on the table with his clenched fist and fingers. The tableau disperses to reveal accompanying musicians and dancers who move into lines of unison. Chairs and tables function as props in this the first of nine dances.

Goya’s paintings portray often fantastical and lurid reactions to war-torn Spain, and his disgust for Spanish political, church and aristocratic leadership. The Inquisition is portrayed, and his own mental instability, due to disease, is noted. Flamenco, a dynamic and ferocious dance form of rythmic taps, seems to imitate guns loading and firing, commenting on the paintings’ scenes of death and destruction. A diversion is the magical Caballo Caído del Cielo (The Horse that Fell from the Sky), where Paula Bolaños, a sensuous and riveting dancer dressed in white, imitates both the horse’s rhythmic, serpentine patterns, and the acrobat’s toss and balance. Bolaños appears on both the main stage and a smaller stage positioned in front of the back brick wall of the theater.

Precise solos, within group dances masterfully performed by the company, reach a pinnacle, and seem to conclude, only to begin again followed by a cathartic coda. Jesús Helmo in Lluvia de Toros (Rain of Bulls), to the superb singing of Gago and Emilio Florido, and guitar playing by Salva de María, dons a bullfighter’s costume, and with verve taps distinctively and powerfully, turning this way and that. Appreciative “¡olés!” came from the audience. La Tauromaquia, (Bullfighting), follows. Encircled by de María and Gago, the stylish Pablo Fraile faces the audience, and then flamboyantly performs lightning-fast pencil turns, and deep lunges tossing his arms in the air. The ever-consummate Barrio dances the final, extended solo, lifting her skirts and bending low in La Puerta Luminosa (Two people Looking into a Luminous Room). On a rectangle of light, Barrio emits a barrage of complicated stomps like the rapid needle of a sewing machine. She acknowledges the accompanying musicians by slowly dipping in a low to high turn repeated several times. After a little jump scoot step, she smoothly promenades the perimeter of the stage.

A solitary figure with cane in hand, and head draped by a blanket as if to ward off sight and smell, hobbles past bodies lying on the floor in Las Camas de la Muerte (The Beds of Death). The bodies, covered by a long white sheet, are pulled on the diagonal. This soundless scene, in contrast to the animated dances, provides a portentously meditative pause.

Why Goya? Why now? Given the pandemic and current politics of oppression, these dances provide a commentary on the inadequacies of the human condition. In the art works, brutality and violence prevail, but this ageless situation is universal and, therefore, always current.