IMPRESSIONS: Kyle Marshall Choreography at The Joyce Theater

Artistic Director: Kyle Marshall

Creative Director: Edo Tastic

Sound Design: Cal Fish, Kwami Winfield

Lighting Design: Itohan Edoloyi

Costume Design: Meagan Woods

Performers: Bree Breeden, Cayleen Del Rosario, Alexandra Francois, Niara Hardister, José Lapaz Rodriguez, Kyle Marshall, Nik Owens

The Joyce Theater

November 8-12, 2023

A thread of spirituality weaves through the evening of world premiere dances by Kyle Marshall. While all three works are distinct, together they create a tapestry of historical reflections that are exploratory rather than didactic. Investigating ritual, transcendence, and the origins of rock-and-roll music, Marshall uses sound and movement to create windows through which audiences can view the past from new perspectives.

Ruin begins like a meditation. Dancers slowly enter a dimly lit stage, stepping over coiled ropes and carrying buckets. Dressed in jagged tunics in shades of ochre and blood red, performers Alexandria Francois, Cayleen Del Rosario, Niara Hardister, José Lapaz Rodriguez and Marshall appear like members of a tribe beginning their chores for the day. These buckets and ropes, “dynamic listening devices” designed by Cal Fish, allow sounds from the ground and air to evolve into Ruin’s soundtrack. As the performers stomp their feet and clap their hands in various rhythmic patterns, Fish orchestrates from a soundboard set up in front of the stage., Fish casts a hypnotizing spell, his score layered with pre-recorded tracks of insect noises, running water, bells and birds. The dancers add to this effect with mesmerizing sculptural movements. Swirling arms and elastic jumps are interspersed with moments of alert stillness, like prey listening intently to gauge the nearness of a predator. While the sounds and movements are uncomplicated alone, in combination they serve to illustrate Marshall’s reflections on early humankind. Each member has an individual yet integral purpose in this community. As Fish overlaps their distinct cadences, they create a musical composition in real time that is discordant but not unpleasant. Dancers perform short coinciding solos and then gather together in unison, eventually arriving at a common rhythm. Each solo accentuates their individuality yet is clearly related to the whole. Late in the piece, the dancers begin to move with more continuous flow, but as the sounds of a crackling fire give way to the hissing of rain they wind down again, this day in their life coming to a pleasing close.

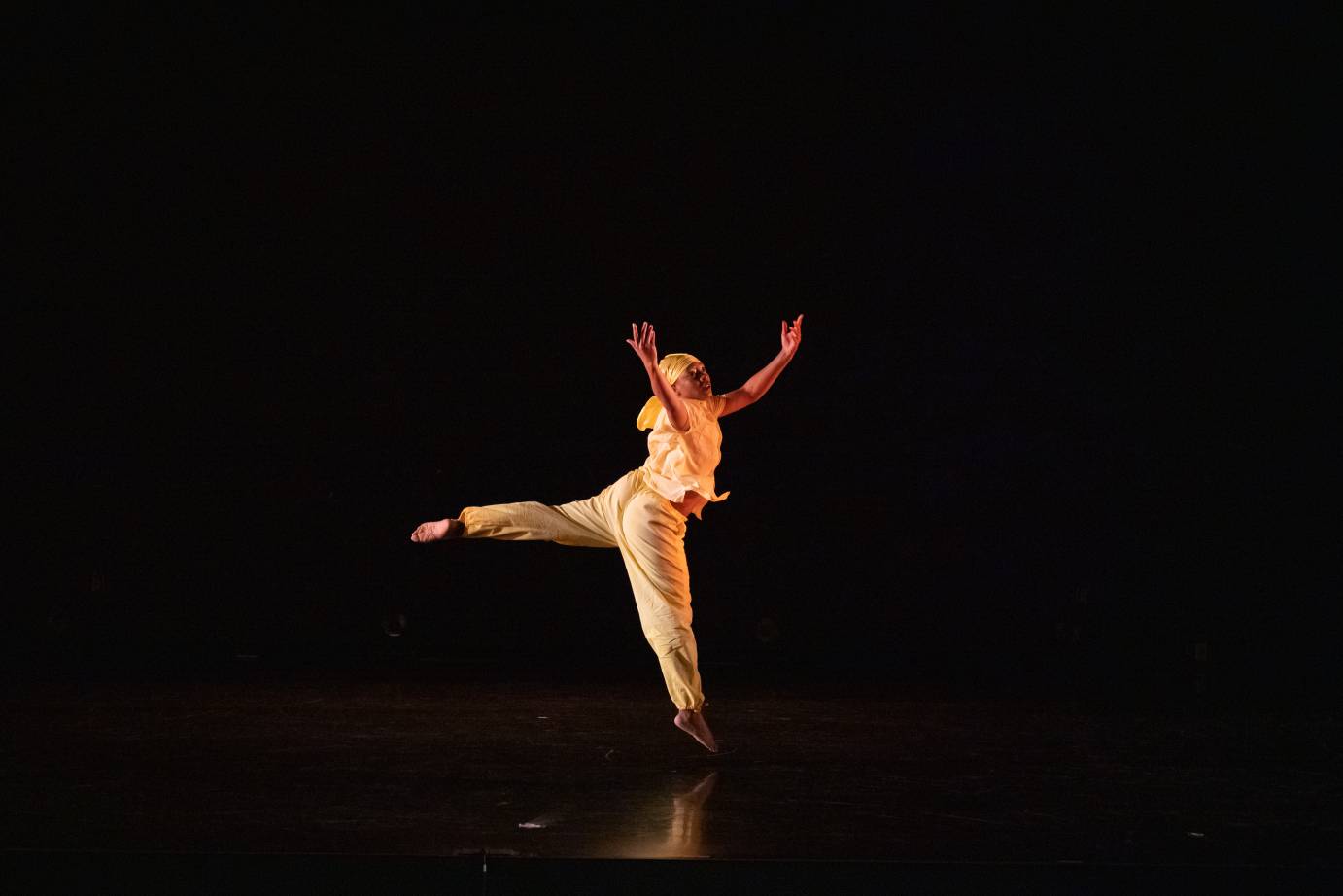

Marshall invites audiences into his mind, prayers and ruminations through choreography that is subtle, contemplative and imbued with deep presence. His dancers are equally as inviting. Bree Breeden in Alice embodies a spiritual journey of transformation. Reaching skyward and bowing in supplication, Breeden personifies three pieces of music by Alice Coltrane with increasing passion and stunning control. With a torso that melts and undulates like liquid, she mixes small isolated movements with powerful jumps as she seeks a higher power. A large mylar backdrop increases the sense of reflection as it catches light. Designer Itohan Edoloyi transforms the stage into a dark chasm from which Breeden seeks to emerge, suddenly illuminating the mylar frame with neon purple, a color often associated with spirituality, creating a portal into another realm.

In fact, Marshall’s entire creative team succeeds at conjuring other worlds. For Onyx, Marshall’s tribute to the Black and Brown musicians who birthed rock and roll, sound designer Kwami Winfield uses echo and reverberation techniques to give classic songs an ominous undertone. At the outset, we hear a blistering guitar riff from Sonny Sharrock overlaid with crowd noises. Breeden backs reluctantly onto the stage as if pulling away from a mob of fans. Winfield’s sound collage samples music and speech from artists such as James Brown, Little Richard, Tina Turner and LaVern Baker and mixes them with radio interference and industrial noise. The dancers begin an understatedly sexy groove, with a captivating nonchalance to their movements, before the music cuts out. Marshall sets up a pattern of interruption highlighting achievements that were often appropriated, undervalued, or eliminated. Dancing to this tumultuous score, Marshall and his cast triumph, embodying frustration, joy, and seductiveness with ease. Their style is casual, yet crisp and precise. The choreography is sultry and sweeping, and sometimes ironic as when Marshall rubs his fingers together in a “where’s the money?” gesture. Dancer Nik Owens, charismatic and alluring, samples movements from the Twist and Mashed Potato as we hear the voice of Little Richard affirming what was stolen from him by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. The voice of Big Mama Thornton growls over and over, “You ain’t nothing” reminding us that while Elvis may have taken “Hound Dog” to the top of the charts in 1956, at heart it is a Black woman’s song of rage at a deadbeat lover.

The majority of historical mentions in Onyx are not as overt, however. Marshall’s message reaches a culmination of feeling rather than depend upon obvious references. The dancers move with manic speed, which then dwindles to slow motion as if in a fever dream. The stage is often dark, lit only by back light, the performers dancing their hearts out in relative obscurity. When proto-punk band DEATH's “Freakin Out’ comes on, the house lights suddenly rise, bathing the theater in harsh white. The dancers shiver, shadowbox then fall to the floor. With the audience in plain view, Marshall exposes the consumerism that enables exploitative systems, then and now.