IMPRESSIONS: Opéra de Lyon Ballet in Lucinda Childs' "Dance " at New York City Center

Part of The Dance Reflections Series Sponsored by Van Cleef and Arpels

Dance

Choreographed by Lucinda Childs

Performed by Opéra de Lyon Ballet (Lyon Opera Ballet)

Music by Philip Glass

Lighting by Beverly Emmons

Costumes by A. Christina Giannini

Original film design by Sol LeWitt

Film re-shot with the dancers of the Lyon Opera Ballet in January 2016 by Marie-Hélène Rebois

Dancers, Dance I: Anna Romanova, Jacqueline Bâby, Jade Diouf, Dorothée Delabie, Tyler Galster, Edi Blloshmi, Raúl Serrano Nuñez, Léoannis Pupo-Guillen, Dance II: Noëllie Conjeaud, Dance III: Marie Albert, Katrien De Bakker, Amanda Lana, Abril Diaz, Jackson Haywood, Roylan Ramos, Marco Merenda, Giacomo Todeschi

New York City Center, October 19 - 21, 2021

Dance, choreographed by Lucinda Childs, with music by Philip Glass, and projections by artist Sol LeWitt, premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1979. The work, in its inception, met with the highest praise, as well as with hurled eggs. Audience members reportedly marched out of the theater. However, since then, Dance’s reputation has grown. It is considered an icon of 20th-century postmodernism and minimalism and one of the canons of modern dance. From 2008 - 2018 Dance toured extensively.

Ballet companies now perform Dance. The most recent is the Lyon Opera Ballet (Opéra de Lyon Ballet), which appeared at New York City Center, October 19-21, as part of the Dance Reflections series supported by Van Cleef & Arpels. Gone is the original reputed ease of the body that created a tension with the strict counts of the music. Dance has appeared live with the original dancers projected on screen until recently. The Lyon Opera Ballet was required to shoot new footage.

Filmmaker Marie-Hélène Rebois captured the Lyon Opera Ballet cast in 2016. Her film recreates precisely LeWitt’s original footage, "a huge undertaking", remarks Childs. With new film there are no comparisons between then and now. Also, the ballet company dancing with itself onscreen produces a sleekness and conformity to which modern audiences have become accustomed. Technique in dance, as with sports, has reached unprecedented peaks of physical prowess. Said Childs to the Lyon Opera Ballet directorship, "we have to redo the film because my dancers from 1980 and your dancers from today — it's just not going to work."

.jpg)

There have been multitudes of reviews of Dance through the years, and across the globe. Reviewers lately prefer the crisp, precise dancing of the ballet casts rather than the blithe execution of the original movers caught in LeWitt’s projections. But wouldn’t it be fun to continue to make up our own minds and compare?

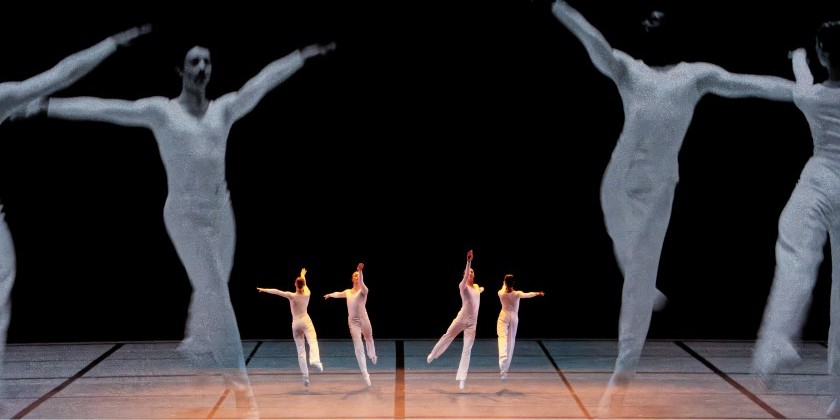

The Lyon Opera Ballet dancers do justice to the steps and the timings. Their precise, smooth dancing meets the demands of the music and choreography. The dance is divided in three sections: Dance I group, Dance II solo, Dance III group. In the first and last sections, eight dancers, two by two in unison, one woman and one man paired, appear on stage with another set of dancers on screen, all moving horizontally across the stage dancing the same steps. The dancers begin stage right and upon reaching stage left, sprint backstage to the other side, and begin a propulsive loop again. Added in the second group section, Dance III, are arcs, diagonals and overlaps.

Over and over, the movement repeats but with increments of change. After a little kick comes a turn, a tilt of the body, a step forward, a small jeté, and, as time progresses, the phrase becomes increasingly complicated. Childs introduces different timings and rearranges the movements. Flawlessly illustrating and interlocking with Glass’ music, these slight changes thrill. Each section continues for 20 minutes, but what a glorious, hypnotic, just-off repetitious 20 minutes. It’s like reading a book that you never want to end or being caught in a dancing reel that comments on past, present, and future. We know from where we come, where we are at present, and where we would be if only we could foresee the future. In Dance, there is a hint.

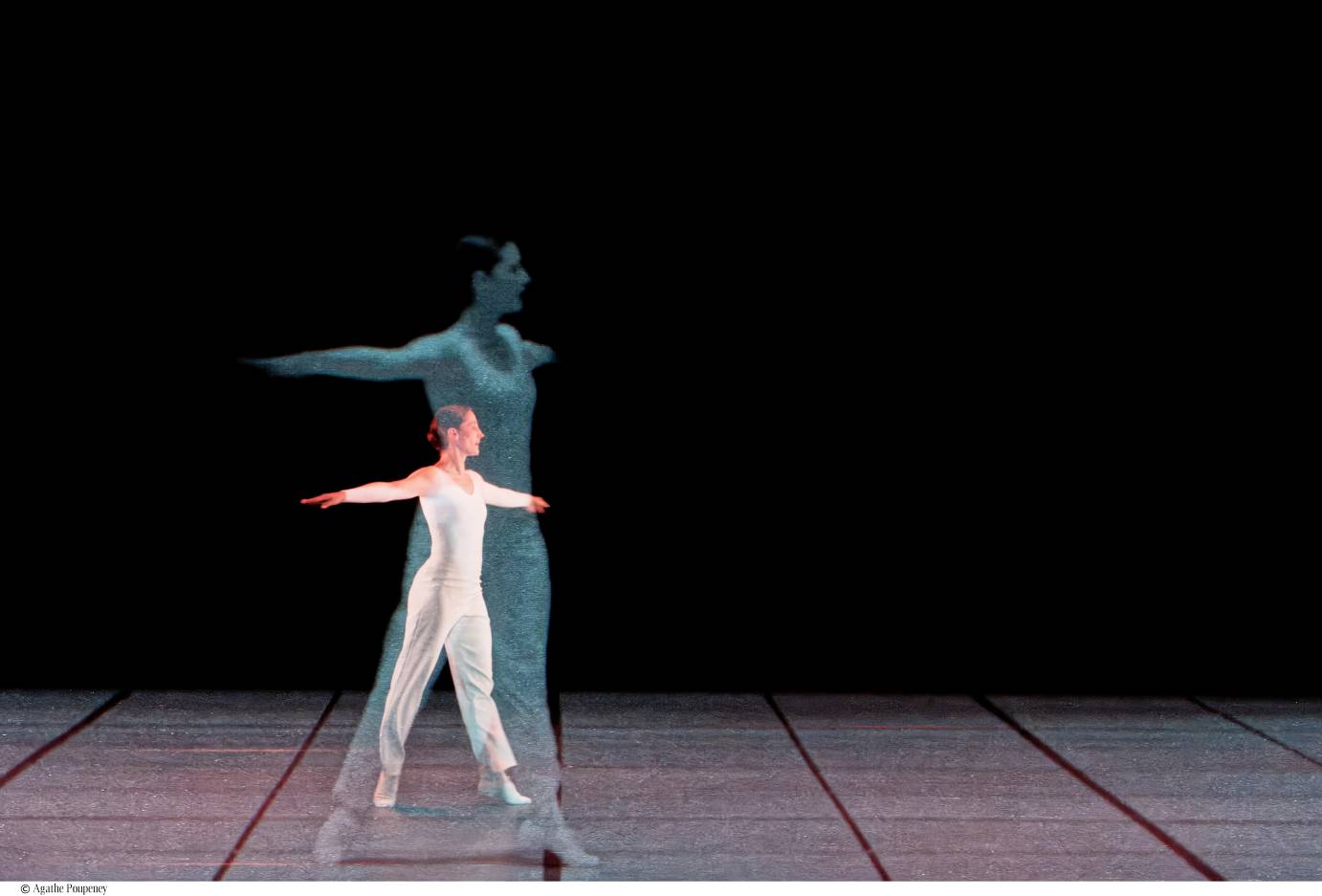

Dressed in white, long-sleeved unitards, the dancers are lucid beings dancing on a white stage floor, and, in the projections, on a white floor overlaid with a black grid. The larger-than-life projections match the dancing of the live performers. The dancers, live and on screen, perform simultaneously. And the film, the decor of the dance, shot from different angles, and then projected on a clear scrim at the front of the stage are located on par, above, below and overlaying the live dancing. The projections refigure and split the space. Still photographs are introduced. As the viewer attempts to follow the multi-directional action, the moments become vertiginous.

Much has been made of the central filmed solo, Dance III, danced by Childs: the way her cool beauty captivates, and no other dancer in the role could match her. Her ice-queen demeanor and her white-hot interior are difficult to recreate. Like most choreographers, Childs’ way of moving guides the choreography. She’s the motherlode.

Danced by the extraordinary Noëllie Conjeaud, in this production, the solo expresses its own crystalline sensibility. The solo offers moments of grandeur and flashes of humor. Conjeaud’s legs kick side to side in a vaudevillian gesture along an upstage to downstage path, opposite to the horizontal path of the groups. Her projected two-story body is captured in a long, opening stillness (as was Childs’), doe eyes alive with expectation, legs in first position, and ready to dance.