IMPRESSIONS: "Never Twenty One" (US Premiere) at Crossing the Lines Festival Highlights Pointless Gun Violence

With Smaïl Kanouté / Compagnie Vivons, Aston Bonaparte and Salomon Mpondo-Dicka

Presenter: French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF)

Venue: Florence Gould Hall, 55 E 59th St, New York, NY

Wednesday, September 27, 2023

Choreographers: Smaïl Kanouté / Compagnie Vivons!

Performers: Aston Bonaparte, Smaïl Kanouté, and Salomon Mpondo-Dicka

Body painter: Luca Flore

Street dance, recorded and written testimonials, and music are the media choreographer Smaïl Kanouté uses to highlight the pointless deaths of young Black men by gun violence in New York City, Johannesburg and Rio de Janeiro. The Black Lives Matter #Never21 movement is the impetus for French-Malian Kanoute’s piece titled Never Twenty One, which his group Smaïl Kanouté / Compagnie Vivons! performed at FIAF Florence Gould Hall during the Crossing the Lines Festival on September 27, 2023.

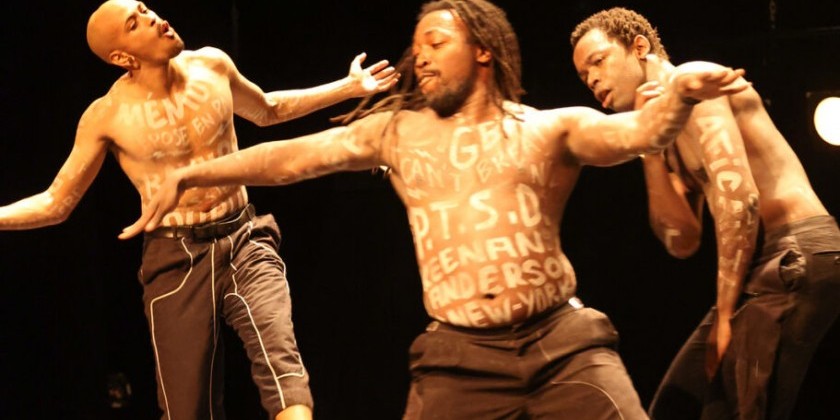

Eye-catching, rippling words of protest are cinematically painted in white on the muscular torsos and arms of the performers, Aston Bonaparte (Guyanese), Salomon Mpondo-Dicka (French-Cameroonian) and Kanouté. (All work in Paris.) Words such as “racist,” “I can’t breathe,” “GUNS,” “PTSD,” “B.O.P.E,” “Nègre,” and “DEATH” in English, French, Xhosa, and Portuguese, describe the fallout from violence, and broadcast the choreographer’s message. Never Twenty One exposes the ‘whys’ of this scourge – racism, poverty, the school to prison pipeline (in the US), police killings, and inequitable laws that affect the marginalized.

Beautifully danced phrases, intense and controlled, illustrate the fraught messages. The performers are well-versed in numerous dance genres, including krumping, popping, house, Brazilian baile, contemporary dance, improvisation, and ballet. Key passages are improvised, so the movement development and energy depend upon the mood and imagination of the dancer. The work, laudably sincere, expresses levelheadedness, but one hopes for dancing that culminates in moments of fever pitch.

Never Twenty One opens on a dark stage. The beams of six flashlights revolve in small circles. Like twinkling stars, accompanied by an eerie, vibrating sound, the orbs move apart and back together. Dim lighting reveals the dancers swaying in a line. They cling to each other, until one falls to the floor as a long note builds in volume to an insistent trill. Flashlights send shafts of light into the audience as if to suggest, “you, sitting there, could be the answer.” One dancer’s feet, spot lit, cross several times, and in parallel, wag side to side. The light shines on another’s arm, across his chest and into his eyes shielded by a hand as if to say, “you, standing there, could be next”. Around and around the dancers run.

This tightknit dancing brotherhood primarily hugs the perimeter of the stage, occasionally foraying onto the diagonal or bunching together before pushing out. Most captivating are the solos danced to powerful messages of grief and anger: “I lost my eldest child. It hurts to talk about it.” Mpondo-Dicka picks up his head with his open hand followed by quick sharp movements of his arms. His spine snakes and his hands churn. Bending his knees, he shrugs his shoulders. “When another child is killed by gun violence, I almost feel it’s happening all over again. 25 years this year and it’s still going on,” laments a mother.

Kanouté’s arms shoot out from his center, then retract. “People are shot 17, 18 times. They’re bleeding all over their body. If I can’t find the bleeding, I can’t stop it,” says a medical worker. Later, to music by gospel singer Fred Hammond, Kanouté’s hands weave, and he prowls in a tight circle, then dips while his wide legs stamp. He is pushed down twitching, his body forming the shape of a cross.

Bonaparte, hands trembling, resumes his upstage seat while Mpondo-Dicka and Kanouté, on either side, slowly walk toward him.

“We’re still mourning our dad’s death. What if he never was killed? My brothers could have gone to college. My sister is still struggling all these years later. I was the only one to pull out of that,” rues a child. Bonaparte, a powerful performer, crosses his arms over his chest, whips his arms around himself, folds his hands in prayer, and lowers his head.

To pulsing loud sounds, the three face each other and slowly move a cupped hand under their hearts. Traffic sounds, car horns, the voices of children playing, South African Zulu clicks, Kanyi Mavi, drumming, Brazilian Passinho Foda and Fumeretto accompany fist pumps, spiraling spines, staccato switches, bounces, and moonwalks. Tributes in Xhosa, Afrikaans and Portuguese express the problems and hope for those societies.

Alone on the stage, wiry Mpondo-Dicka moves like a tap dancer, percussively striking the floor, followed by high kicks backward. “I lost a lot of friends,” intones the voice of a young man, as Mpondo-Dicka bends over in a sobbing motion, “I lost a lot of friends,” the voice repeats as Mpondo-Dicka’s knees fold until he nearly touches the floor. Pulling at imaginary hair, he walks with deliberation upstage as the lights fade.