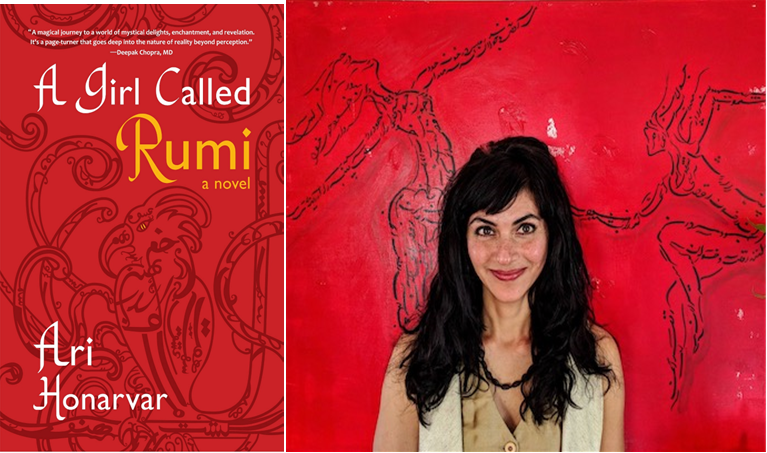

THE DANCE ENTHUSIAST ASKS: Ari Honarvar on Creating the "Dance for Freedom" Movement, Supporting the Women of Iran, and 'Dancivism'

San Diego-based Iranian-American dancer, critically acclaimed author and visual artist Ari Honarvar uses the term “dancivism” to describe her work bringing the healing power of dance to refugees from all over the world. As a teenager, she escaped from Iran, where dancing is illegal, and came to America alone, finding refuge in the freedom to dance in communion with others.

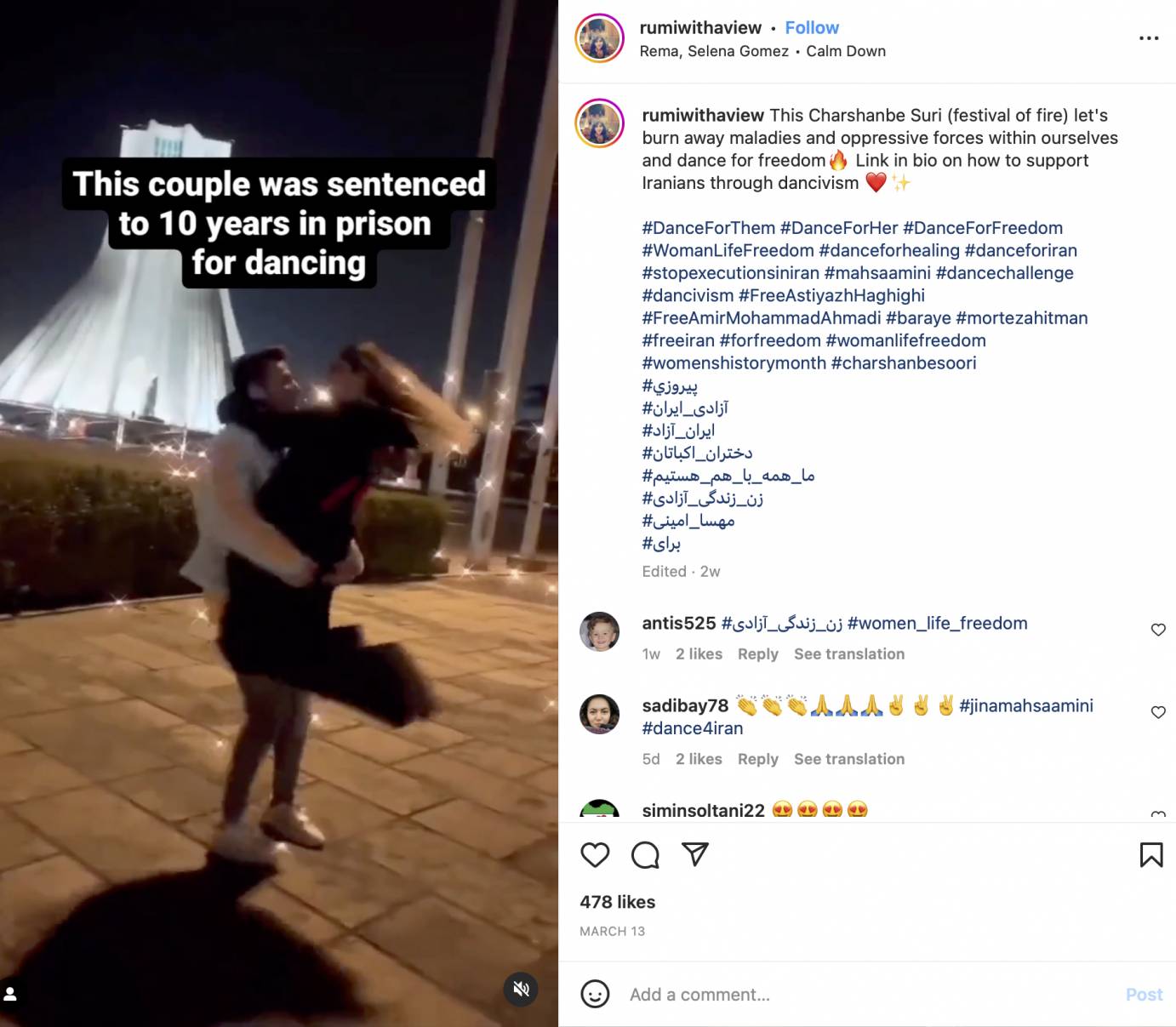

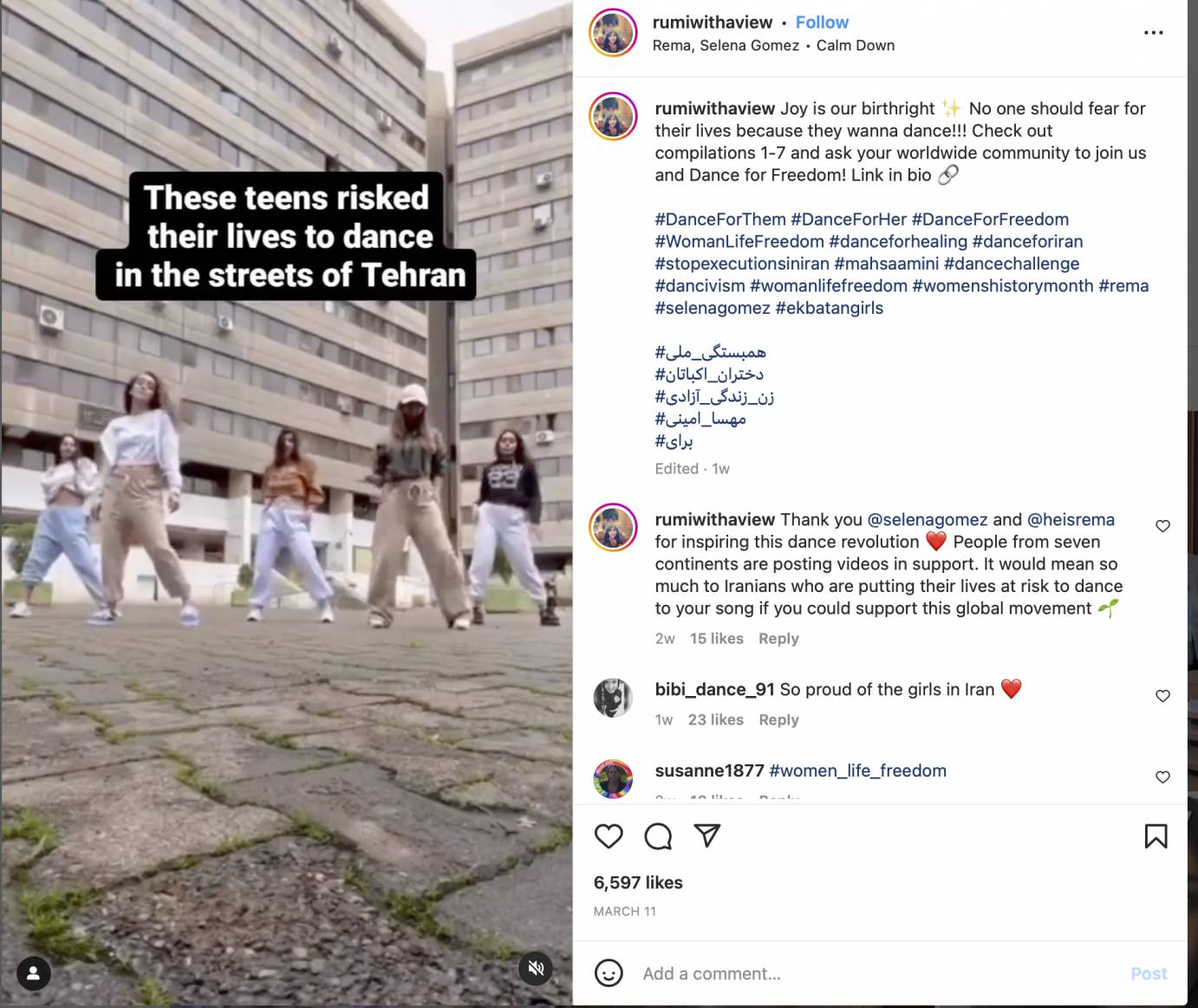

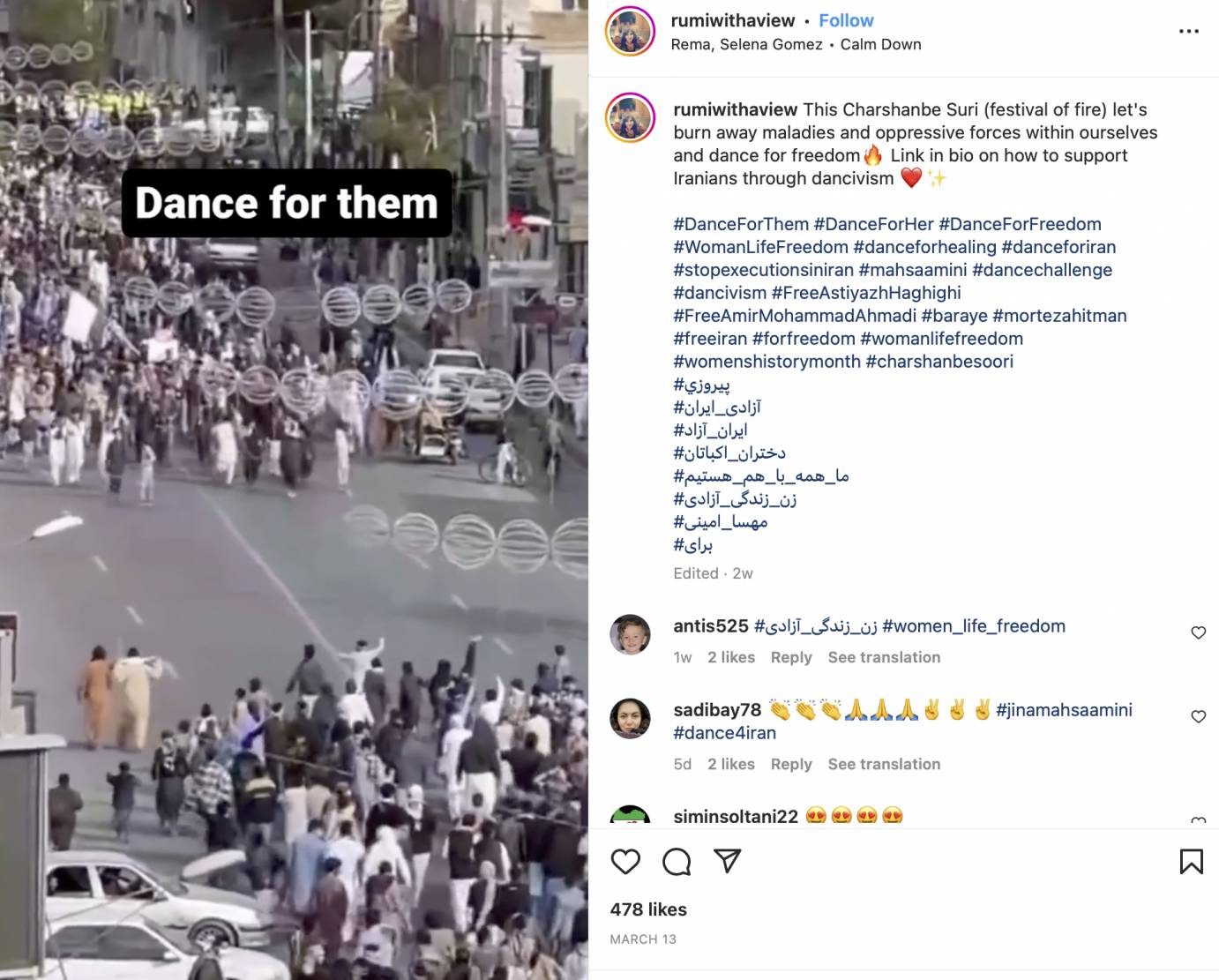

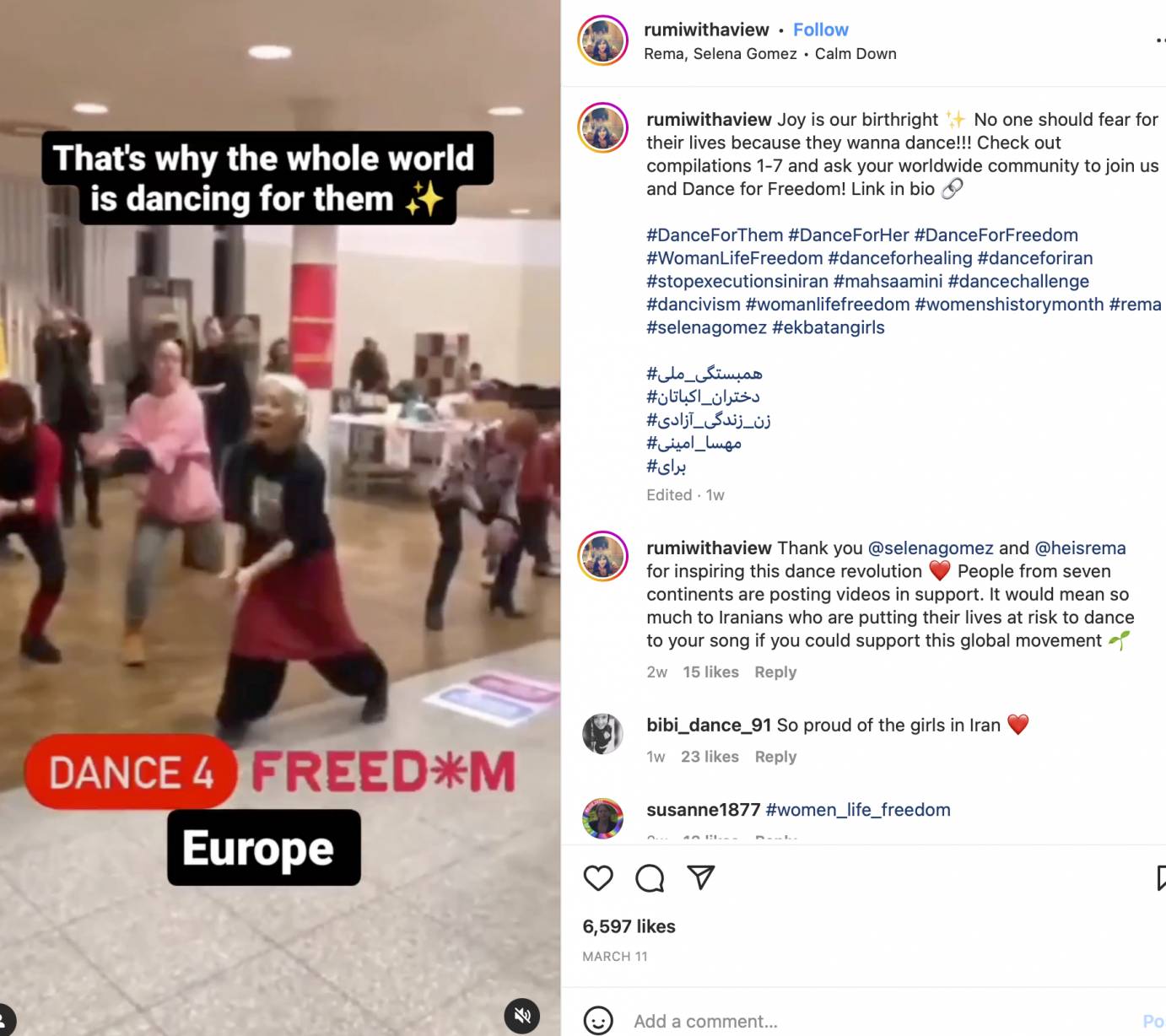

Her latest project, Dance for Freedom supports protesters in the largest women-lead movement in modern history, bolstering their battle for basic freedoms, like the ability to dance without fear. Dance for Freedom brings attention to the intersectionality of social justice causes, forging connections between persecuted populations all over the world, and grounding us in the common language of dance as a message of support and solidarity.

In an interview with The Dance Enthusiast, Honarvar speaks about the deeply personal roots of her work, and the connecting capacity of dance.

Theodora Boguszewski for The Dance Enthusiast: I’d like to start by asking you to share a bit about your background. What was your childhood like, growing up in Iran? How did you come to the United States?

Ari Honarvar: I was six when the Islamists took over the government and singing and dancing became illegal. There was a war with Iraq that started shortly after that – Saddam Hussein took advantage of the internal turmoil and attacked Iran. That war lasted 8 years and destroyed millions of lives. We were being attacked from the outside, and our civil liberties were being attacked from within, there was a war on free expression and dancing, a war on joy. We summoned joy as an act of resistance, and took risks that could end our lives.

My sister’s classmate was executed when she was 16 — we don’t know why, they never told her parents, there was not a public trial. So my parents were like, “We’ve got to get her out of here.” I came to the US at the age of 14 under extraordinary circumstances, and without my parents. I lived with an American family for a while, and as I was getting acclimated I danced a lot. Dancing helped me mitigate the effects of my childhood trauma and decrease my incredible homesickness. Now I bring what was denied to me as a child — which was music and dancing, and what I really longed for as a newcomer, which was a sense of community — to other refugees.

It’s amazing work that you are doing. How were you introduced to dance?

It’s part of my culture, I danced before I knew how to talk probably, it’s such an easy way of expressing yourself. I’m not a great dancer, what I use it for is a way of healing, a way of bringing community together, a way of just being human with other people.

So dance was part of your childhood, and then at a certain point it became illegal, and you just weren't allowed to dance anymore?

Right.

How did you discover a dance community in the United States when you came here?

I lived most of my life in Austin, TX, which is the live-music capital of the world, so if there was music I would be dancing to it. I was very unselfconscious about my dancing. I took one or two belly dancing classes with a great Greek dancer, and then I got interested in salsa and meringue and kumbaya, and then there was the barefoot boogie and body choir, those kinds of hippie places where you just go and dance with other people.

Tell us about Dance For Freedom, which premiered on last month. Was it a single day event, or a launchpad for something that will continue to grow?

I’ve been part of the activist world for a long time and I see so much burnout. It’s not sustainable. I thought: How can I bring activism to the plight of Iranians, who are fighting for freedom of expression? Dancing is illegal in Iran, so why don’t we use this term "dance-ivism," and dance for people whose bodies are barred from dancing? We can use our bodies, just like we use our voices, to amplify their voices, their cries for freedom.

It brings joy to Iranians who can see that the rest of the world hasn’t forgotten about them. It wasn’t just in the headlines for one day, this can be an ongoing thing. We started on February 10, 2023, and I still get videos from different parts of the world. It’s a global movement. Everyone is participating and it’s so exciting.

What I also love about this is there is an interconnectedness with social justice causes. When farm workers dance for Iran it brings attention to the environment, when Indigenous dancers dance for Iran it brings attention to the Indigenous dancers and their plight as well. We have one guy from Uganda who works with former child soldiers and uses dance as a way of rehabilitating them back to society. It feels like it’s always either or, like we can’t have Black lives matter and feminism at the same time. But that’s not true, and to bring these movements together is something that is so needed right now.

How does that message reach Iranians? Is it difficult for them to have access?

Well, there are definitely internet blackouts and crackdowns on social media, but people are very resourceful living in Iran, they have ways of getting around the censoring.

Can you share any specific videos that felt particularly powerful?

Oh, so many! There are little preschoolers who are dancing, and just kudos to their teachers and their parents, they are just so enthusiastic. There have been videos of senior citizens from all over the world doing this traditional Kurdish dance together to music. There’s a Ukrainian refugee, doing a beautiful dance in nature. There’s a woman who was arrested for dancing in Iran, she lives in Berlin now, and she’s very enthusiastic about this project.

I hear you are a Music Ambassador of Peace, and that you design these programs for refugees. Can you share a little bit more about what it means to be an Ambassador of Peace?

The goal is to bring cultural bridges to places where the political dialogues have collapsed, to bridge people to people through music and dance. I’ve danced with Syrian, Ukrainian refugees, with Iraqi refugees, with people who have been freed from ISIS enslavement, with unaccompanied minors who came by themselves from Central America on foot to seek asylum in the US. I’ve danced with Venezualans, South Americans, Haitians, Africans, everywhere.

And is a lot of that work happening over Zoom? Or in person, or both?

During COVID we had to switch to Zoom but I would go over to the refugee shelters in Tijuana and Mexicali when I could. Now I have weekly sessions over zoom, I dance with about 300 refugees every week, and then I go every month to Tijuana.

What are the pros and cons of using technology to do this type of work?

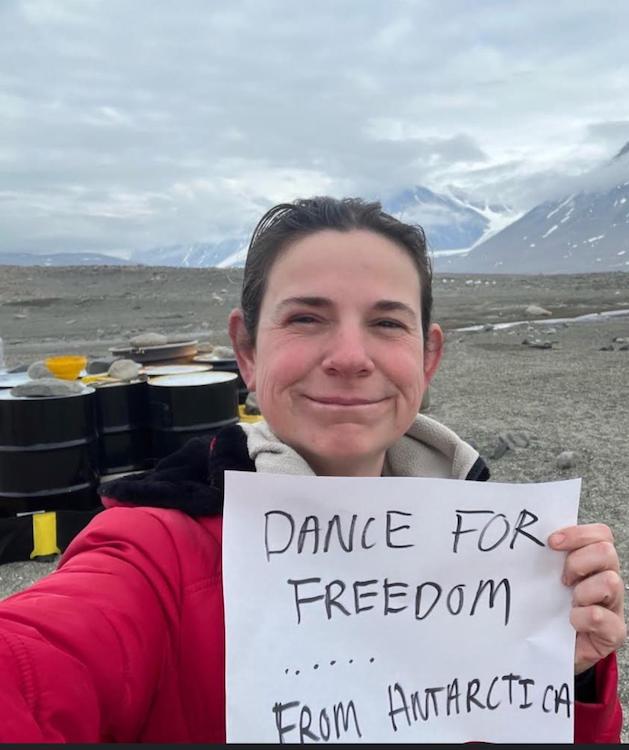

Well, there is no other way to do it. I am very much aware of the damages of being too focused on your devices, and I feel it in my body when I have to be on social media for an extended period of time, it’s like a hangover. But it’s the only path to get the message to 7 continents. Like, a woman in Antarctica, who was able to connect with me through social media. There are scientists in Antarctica dancing for Iran,which I think is super fabulous.

I was reading about your work on the same night that I got dinner with a friend who is recovering from a stroke, and she was describing what it meant to re-learn how to be inside her body. I was thinking about how, when you don’t have a home, you have to find this home inside of your body.

That’s such a smart way to put it, and that’s exactly how I describe the refugee situation, is that we have to find a sanctuary within ourselves when there is no external home. Because music and dancing evolved before language, so it’s such an integral part of being human, it’s so easy to tap into that as a way of finding an inner sanctuary.

In addition to being a dance activist, you are also a painter and an award-winning author. How do your creative processes in these three mediums influence one another? Does your writing and painting inspire your dancivism work?

Moving my body to music always helps get the creative juices flowing. It's not unusual that I find solutions to my writing problems during or after dancing. These solutions can range from seamlessly piecing sections of my writing together, to filling in plot holes. When I paint, write about, or speak of dancing, it highlights all its benefits and that also inspires me to continue the practice of dancivism.

I find myself dancing a little after I finish a piece of art or writing too. It has a way of integrating the experience while I celebrate the joy of accomplishment.

Before we finish, do you have any final thoughts for our audience?

What I am very curious about and what I notice is that, while Iranians are dealing with an actual morality police, an internalized aspect of the morality police is a global force. People judge themselves and others for dancing, and dance is probably one of the most stigmatized forms of art. We are body shaming ourselves, and we also do that to each other. I wish that this work would get around that problem of the inner morality police, and that people would dance in their bodies. I want that freedom for everyone.