Impressions of: Damn Good Featuring Launch Movement Experiment, the feath3r theory & Coco Karol at Triskelion Arts

Impressions of Damn Good Series Vol. 1

Curated by Rachel Mckinstry and Andy Dickerson

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Featuring performances by: Launch November Experiment, raja feather kelly / the feath3r theory + a short-form performance by Coco Karol

Triskelion Arts

When curators Rachel Mckinstry and Andy Dickerson (also Triskelion’s Lighting Director) set out to create the series Damn Good, they aimed to “bring together artists who resist categorization and invite experimentation.” The inaugural weekend featured works created by singular artists who challenge and provoke the world around them.

In many shared programs and festivals, lighting can be non-existent or an after thought due to limited tech time. But in Damn Good, Dickerson’s lighting design is intrinsic to the overall vision. The result is a distinct and different texture in each piece.

Coco Karol opens with b-sides. Three figures — flaxen curly-haired Karol, Miguel Guzman, and Lacy Rose — gesticulate in semi-darkness as they face an exposed mirror on a wall. A disco bowl slowly whirls in hazy light evoking a nightclub at dawn. The performers, in provocative sequined and lace garb, stumble about. Rose sings an original poem while Karol flits around her, a sorceress conjuring verse out of her possessed vocalist. Despite his technical aptitude, Guzman often feels ancillary to the scene. b-sides’ sumptuous scene is not enough to be pulled in. Like a record skipping on the needle, the dance goes round and round without moving forward.

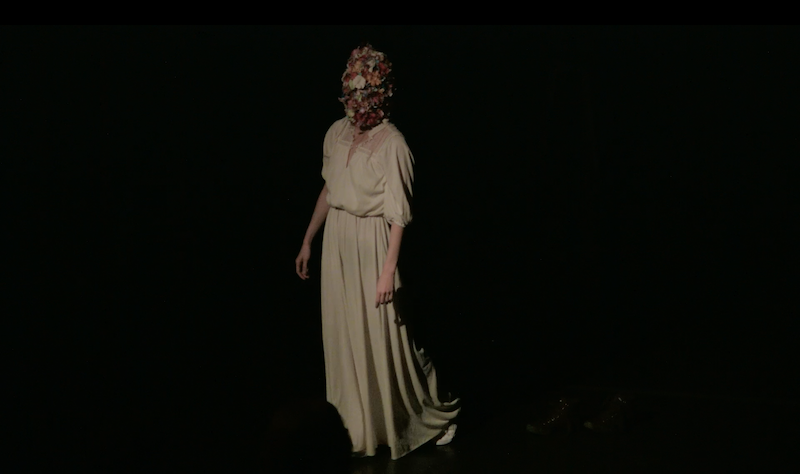

Raja Feather Kelly’s Oh could be named Bertha Mason: The Untold Story. (Mason, a fictional character in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, was Rochester's mentally ill first wife who was locked up in their attic.) At first glance, the comparison may be a stretch. Oh soloist Sara Gurevich doesn't burn down a house nor does she destroy a wedding veil in an enraged fit. Then there's the Usher song that reoccurs throughout the piece. But Gurevich delivers a catatonic and unbridled performance reminiscent of Mason’s temperament in the novel.

First appearing in a head-to-toe black unitard, Gurevich penetrates the space with detail and skill despite her obstructed vision and chaotic lights pulsating from all sides of the stage. She is judicious with each gesture — no movement outweighs another as the light envelopes her in darkness. She soon shifts from this enigmatic persona to an Edwardian woman who reads in a flat affect the Anne Sexton poem “Oh.” The poet, like the fictional Bertha Mason, battled depression and mania; she ultimately committed suicide in 1974. In the final moments, Gurevich, wearing a filmy white frock and a floral mask, meditatively traverses the stage following a tunnel of light reminiscent of mist. The question, “Is she marching to death?” nags with considerable force. We never do find out as the harrowing soloist leaves us in the dark.

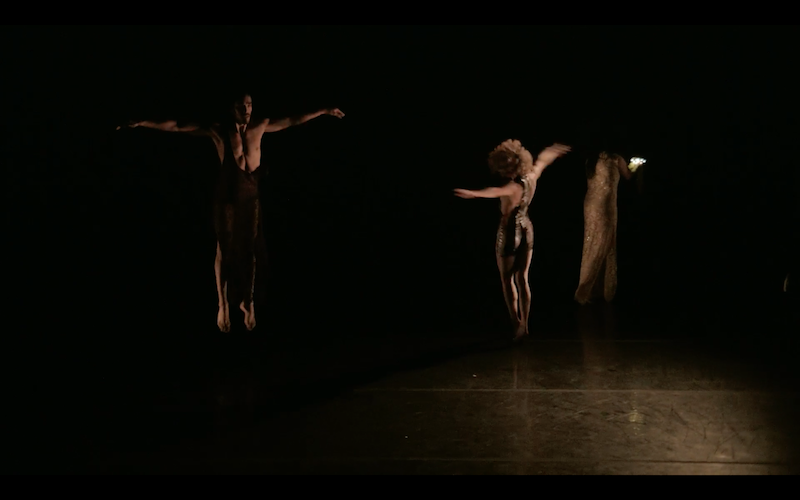

A ghostlike presence returns in The Launch Movement Experiment’s cabin. The work opens with lanterns swinging from the ceiling, glowing amber — not a soul in sight. Eventually Mckinstry with dancer Anne Zuerner, circus artist Perry Garvin, and guitarist Kevin Farrell reveal themselves. They move cautiously throughout the space and gaze at the ceiling. Are they looking for a way out? Their sense of urgency gradually increases, emphasizing this question.

The Launch Movement Experiment collaborators often improvise, from sound to lighting to movement, in performance. cabin is no different. At times the spontaneous nature excites. Garvin in an upstage doorway — his movements imperceptible yet deliberate — while the dancers downstage contrast with a flurry of limbs makes a compelling viewpoint. Dickerson assists in bringing attention to these spontaneous moments of beauty. Enlisting a soft low light, he highlights Mckinstry in a sinewy phrase as she slithers on the floor. Later, he brings up the light in a lantern as a hand lingers over its glass casing — cinematic in its framing.

At times, though, the improvised dance stalls and meanders. In these moments, Farrell proves to be an interesting distraction. He doesn't so much play the guitar as dance with it. Back hunched and legs splayed, he plucks the strings with violent dexterity. Abruptly concluding, cabin holds onto its suspense. Will its inhabitants ever escape?

The most captivating aspect of the evening is Dickerson’s innovative lighting design. Even when the works miss the mark, his artful choices make up for what is not there.