AUDIENCE REVIEW: Tabula Rasa Dance Theater presents "One Of Four"

Company:

Tabula Rasa Dance Theater

Performance Date:

July 2021

Freeform Review:

During the opening of Tabula Rasa Dance Theater’s latest show, “One of Four,” the audience hears over the sound system five different tales of sexual assault, recounted in male and female voices. Rapidly, the individual stories begin to overlap and merge into an indistinct chorus. From the outset, Felipe Escalante, the company’s Artistic Director and the choreographer of “One of Four,” conveys to his audience the universality of his troubling subject matter, gender-based violence. According to the program, which comes with a trigger warning, Escalante took the title of his piece from the shocking statistic that one out of every four college students in the United States will be raped. But he also makes clear in this supremely beautiful and disturbing piece that this human rights issue extends beyond American campuses to include all cultures, and all time periods.

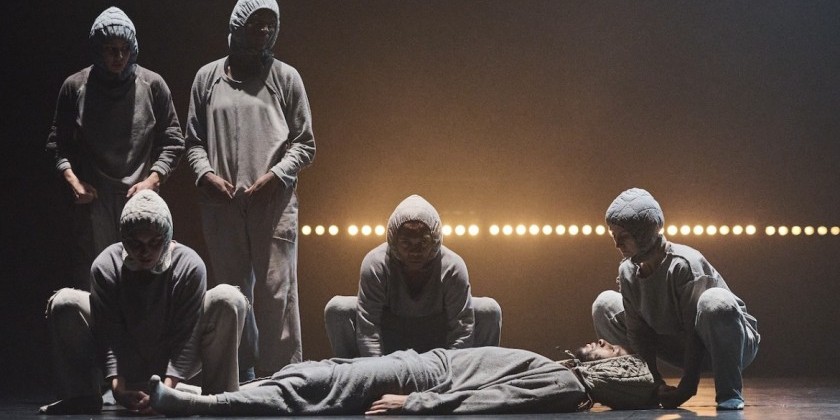

During this spoken prelude, five dancers, holding either a black or a white life-size, articulated mannikin, begin to move hypnotically. They sway, crawl, hop, kneel, and arch on the floor or walk solemnly, holding a doll aloft. The space in which they perform has been blocked out with black tape into a checkerboard of four squares. As the disembodied voices fade into silence, they are replaced by angelic live music. Seated outside the squares, tenor Christopher Preston Thompson begins to sing liturgical songs in Latin, composed by the 12th-century nun Hildegarde von Bingen and others, accompanying himself on a medieval harp. The switch from profane to sacred is startling, but then so are so the animalistic, convulsive, sensual movements of the dancers, partnering with their faceless, jointed dolls.

As inseparable from the dancers as their own shadows, these cumbersome, lifelike dummies are swung, flipped, draped, choked, caressed, cradled, and manipulated in increasingly inventive ways. Sometimes a doll’s leg, arm, or hand is confused with an actual flesh-and-blood extremity, as when Myles Hunter ambulates on all fours, while his mannikin, arms dangling to the ground, lies supine atop his back. Real and artificial bodies recurrently fuse into sculptural, tangled masses, recalling such art-historical groupings as Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of the Sabines, or Bernini’s Pluto and Persephone. (These lecture-hall staples only begin to give us an idea of how much and for how long Western culture has normalized rape—and that, we understand, is one of Escalante’s points.)

The “One of Four” mannikins (created by dancer Noriko Naraoka), unmistakably represent abusers, and the emotional and physical burden borne by survivors. No matter how strenuously the performers try to detach themselves from their dolls, they are ineluctably drawn back to them. The weight of these unwieldly figures (they are about 60 pounds) bears down painfully on these struggling humans. Their facial expressions sometimes evoke tragic masks or silent screams.

The mood shifts during the sequences when the ethereal notes of the tenor and his harp give way to the frenetic pulses of a recorded electronic composition by Mano Goreda. The dancers do not interact with each other as they gyrate and twitch, only with their symbiotic, inanimate partners. The dummies are nimbly maneuvered into deforming, invasive positions. Occasionally the roles reverse, and the simulated assaulters seem to submit to violations from their victims.

These reversals suggest how victims often believe they are to blame. They also intimate that victims can, in turn, become victimizers. Whatever the intended meaning, the choreography, with its somber clarity, demonstrates that once trauma enters the body or mind, it never leaves.

Just as the male and female voices converge during the prelude, so the genders of the dancers and of the dolls are ambiguous or irrelevant. Both the male-identifying and female-identifying artists wear full, tiered skirts, in either black or in white. Sometimes the costumes connote shrouds; other times they look angelic. The vocalist, too, wears a skirt, though his is embellished with vertical black-and-white stripes, echoing the strings of his instrument.

The approximately one-hour piece concludes with a harrowing solo by Naraoka (actually a pas de deux, if one factors in the doll, now seated cross-legged and angled inward). Concave and cowering, she appears to confront her featureless attacker, lunging toward it, then retreating from it, fingers crooked into spikey claws. She swivels, thrusts, and stumbles, shuddering with anguish, fear, and ambivalence. After this climatic passage (reminiscent of early Graham), when the dancers bow and file out, they still clutch their dummies, almost in an embrace.

“One of Four” is an ongoing program that has been performed in various outdoor public locations (Sunset Park, Van Cortlandt Park, Hudson Yards, Marcus Garvey Park) and indoors at the Nureyev Studio at Ballet Arts. The show takes on different nuances depending on the setting, and audience responses vary accordingly. At a Ballet Arts presentation, many of the masked attendees wept. Escalante danced only in the two shows at Ballet Arts, which were also livestreamed. In one segment featuring just Escalante, Hunter, and their dummies, the choreographer undulated, thrashed, and pinwheeled with such exhilarating ferocity, he seemed almost to liquefy.

At every Tabula Rasa Dance Theater performance Escalante incorporates a self-absorbed “Phone Lady” or “Phone Guy,” characters who sit on the sidelines compulsively swiping and scrolling away on a smartphone or taking selfies, desensitized to the suffering around them.

During the Hudson Yards performance on July 22nd, art neatly imitated life when one brazen onlooker penetrated the fourth wall and started posing for her companion’s iPhone camera. A Hudson Yards security guard, noting that the woman was not a member of the company, whisked her off the dance floor. The rest of the audience, including some toddlers, remained transfixed by the performers, and the show went on.

Critic’s note: It has come to my attention that, in order to make up for pandemic losses ballet teachers and dance studios have increased their fees. By charging more than they did pre-pandemic, they are further suffocating the arts. If anything, they should be discounting classes and rehearsal spaces so that dancers, whose already precarious economic situations were further damaged by COVID-19, can continue to practice their art. Some of the company members now can no longer afford to take classes at ballet studios. Tabula Rasa Dance Theater has had to limit rehearsal time because of these rent hikes. Please join us in vocalizing your dissent.

Author:

Sylvia Susskind

Website:

www.tabularasadancetheater.com/

Photo Credit:

Russell Haydn