AUDIENCE REVIEW: On Audre Wirtanen’s DX ME FIX ME, on spinning, on thinking your way out of your body

Company:

Audre Wirtanen

Performance Date:

March 5, 2020

Freeform Review:

Audre’s handout, passed around after the performance of her new work, DX ME FIX ME, guides us, the audience, in how to engage with her work. Before asking us to reflect on what we experienced, she writes “Check in with yourself” “Notice you are breathing, you are on the ground.” With these directives, I feel cared for. She had anticipated that I might need this. She had preemptively empathized with her audience. I feel cared for, and immediately notice (as per the next instruction “What did you notice about this piece?”) that she did not get this same level of care from the doctors she described, impersonated, and portrayed in her work. None of them attempted to preemptively empathize. They were the “the men who fucked me,” as she writes on a giant post-it pad in the middle of the stage at one point during the piece.

She also asks us, through the handout like a portal from her brain to mine (I am neurotypical, I am not disabled, I have not dealt with doubt of doctors as she has, and I think she is talking to me), “Do you feel bad for me?” “Did it scare you?” “Are you trying to analyze whether or not this piece is real?” These questions give words to ideas that had only started to form in my subconscious--she gets out ahead of them. She also asserts “Eugenics is real.” She insists “Be ANGRY” “Be LISTENING” “Be willing to LEARN.” She provides resources and readings and podcasts to do the anger and the listening and the learning. This clarity, authority, and passion is solidified in this document, but has already percolated through her work I just witnessed. She is unafraid of confrontation and explicitness, and unafraid of dense nuance.

The work itself began with a “content warning” Audre wrote on a big pad of paper. This also serves as explicit context for the work, a guide of sorts. “Eugenics.” “Sexism.” “Ableism.” I consider my able, femme body. I consider my entrenchment in western biomedicine through a doctor grandfather, a doctor aunt, a doctor sister. I consider my embeddedness in the world of dance and somatics, my fairly smooth and rosy experience through it from liberal arts college to NYC. I try to consider my ableist gaze then and now.

In DX ME FIX ME, Audre travels among her stage of props, a world she seems steeped in--a book, a blazer, an IV stand, clipboards, doctor’s stools, cups of yellowish liquid--telling us her near-diagnosis, or more aptly, misdiagnosis, of P.N.E.S.

One of her first stops is at a book written by the founder of Alexander Technique, a somatic practice that attempts to release the body of tension and create balance. She reads from the book in an almost-mocking tone about “disability finally being eliminated” and the “evils of bad habits.” She is presenting written evidence of eugenicist rhetoric in somatics, showing clearly how we are told the body is something to fix. She lowers the book over her face, her body prone on the floor, reading reading reading until the pages seem to drown her voice. She is smothered, and I wonder if there is room for a body that can’t be “fixed” or doesn’t want to be “fixed” in that book. She throws it across the stage. I am ready to get angry with her.

She tells the audience, with a colloquial tone but using specific medical language, about her doctor’s visits, travelling from a clipboard to the giant note pad to an imagined doctor’s office. I learn a cohesive narrative of a search for an explanation for involuntary movements. I hear lists of symptoms, names of men, diagnoses, and endless experiments. I meet those who have tried to fix her--she embodies doctors she’s seen, making easy fun of their “masc-cis-het energy.” In the first of these meetings, Audre, after spending three days tethered to a wall in a hospital by wires and stickers that measure her movements, is met by a doctor who is stand-off-ish, literally--he won’t even come into her room. A psychiatrist is hunched and indifferent as he asks about her history of trauma, while Audre flips her body over and over trying to explain it. An “expert” is manspreading and inching towards her, telling her she’s attractive. Her pants are removed by her hands but I can’t be sure if they are her hands, really. I can feel his gross sexualized paternalism from my seat. By playing them she exposes them and we get to laugh at them together. I am angry.

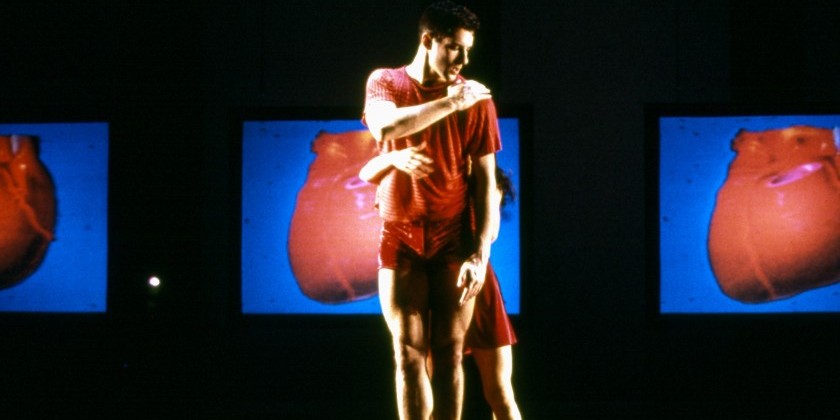

Throughout, when playing herself or acting as a narrator, her movement is slippery and self-assured. She dances with her top half exposed except for EKG stickers covering her breasts, and her casualness makes me forget she isn’t wearing a shirt. She bends herself through a folding chair, glides softly in a rolling stool. She is constantly moving when playing herself, working working working to provide enough information (proof?) of her symptoms and pain. When she learns from a doctor about P.N.E.S., defined at one point as the brain “converting stress into physiologic symptoms,” she shares its many names: P.N.E.S. was once conversion disorder, which was once hysteria, which was once was the medicalization of witchcraft. She is floating while telling us this, spinning on a stool, her limbs slicing air with a kind of weightlessness. Her voice sounds almost giddy at the ridiculousness of being diagnosed with behavioral “spells.” I feel entranced.

Later she traverses her long row of clipboards, pulling on hospital socks and a blazer. She rubs a piece of paper over her skin (which I later find out is the business card of a social worker who hit on her during a consultation), bites it, chews it, swallows it down with a plastic cup of yellow liquid, her eyes trained forward steadfastly, determinedly. I wonder if this is how it feels to try to ingest and adjust to diagnoses, attempting to integrate them into the body. Or if this is how it feels to “follow doctors’ orders” or maybe to do the opposite. Or maybe if this is how it feels to get bullshit diagnoses that feel as useful as a tiny piece of paper slipping down the esophagus, washed down with sugar water. She ends this trek at a mirror where she readjusts her hair, methodically paints her lips, and recites the history of “hysteria.”

In what feels like the climax of the piece, Audre has pressed her belly into the doctor’s stool and uses her hands to spin herself, her head hanging and her legs outstretched. She speaks words at herself. They are someone else’s words, but seem to have been bouncing (spinning?) in her head for a long time:

I told you, it’s your thinking that’s the problem! You could help yourself but you are not thinking! You are the reason you are sick! You can think your way out of your body. I have. I can help you. I can fix you.

These words are familiar to me, more than the lists of symptoms or diagnoses. I have heard the promises of somatics and meditation and yoga and postmodern dance over and over again. I have chased the idea of being able to fix myself, of exiting the truth of my body or the reality of my history and transcending into some sort of “freedom.” I have been told to think my way out of my body too. I know my understanding of this rhetoric is limited--I am able, I am white, I have class privilege. But I see that these words and promises of fixing do not constitute care.

DX ME FIX ME is dense, packed not only with objects but also with medical vernacular, singing, heavy memories, and frank statements. I find it hard to summarize the experience in its entirety. But maybe this is the nature of her experience in searching for answers that are elusive and manipulated. She has shown me how much proof it takes to be taken seriously, how much authority she has to show to be believed, how much labor she has to do to just get some fucking care. She has repeated the exercise here on the stage; I have been confronted with the reality of eugenics, manifested in stand-offish doctors and sexist diagnoses and dismissive men and ableist somatics work. I am angry, I am listening, I am learning.

Author:

Nora Raine Thompson

Website:

https://norarainethompson.org/

Photo Credit:

Scott Shaw