AUDIENCE REVIEW: Chen Dance Center presents newsteps: a choreographers series

Company:

Chen Dance Center

Performance Date:

April 11-13

Freeform Review:

Chen Dance Center presented newsteps, a choreographers series this past weekend at the Chen Dance Center in New York’s Chinatown. Five choreographers were given rehearsal space, an honorarium, and mentoring from a member of the selection panel to create a piece less than 10 minutes in length. Chen Dance Center has been operating for 40 years; the newsteps series has already seen about 50 iterations. To some extent, one might wonder how anyone can create something that hasn’t already been done before. But as the night showed, each piece, through deep investigation into their own themes and movement, found ways to evolve past or directly challenge the status quo.

When the lights come up on Mat Elder’s LONGO: Traction, two dancers (Morgan Hurst, Meredith Santoro) are face to face in a standoff. Who’s going to give first? Slowly, one inches forward, the other retreats, is pushed into one of the six chairs strewn about the stage. Their gaze, locked on each other, never break. For most of the piece, the focus is on the relationship between these two women, the tension between them as they advance and pull back, seize control and suddenly collapse, caught in a never-ending cycle of posturing and posing in relation to each other. Tension is built through stillness, confrontation, and repetition.

While the two women are focused on each other, Zachary Denison is in the background, at first a shadow, mimicking the women's movements. Later, he manipulates the world around him, arranging and rearranging the six chairs like chess pieces while the dancers maneuver between them. The tension and movement in the women's duet continue to escalate until the end, when Denison is thrown into a tumbling, whirling solo. He falls to the floor, gets back up only to fall once more. The lights go dark on the dancers stuck in the same loop of collapse, rebuilding, and collapse.

Also confrontational, but in a quiet, subdued way, was the second piece on the program, Annie Heath’s Unidentified Sheep Scouting. The piece starts with her facing away from the audience, both palms and feet flat on the floor, legs extended and her bottom high in the air, basically right in the audience’s face. After a short pause, she begins trotting, back and forth from the audience, limbs loose and silky. The first time we clearly see her face, it is upside down, between her legs.

Heath shifts and morphs, from crawling to slowly rolling on the floor to vigorously undulating on all fours. The movement is frequently purposefully awkward, such as when she supports herself on the inside edge of her hand, her wrists splayed out like the pointed hooves of a sheep. At one point, she almost stands up, her body curled into herself, but quickly returns to the floor. At times, she fixes her odd, quiet gaze on the audience, acknowledging that yes, her butt is in the air, and yes, these positions are awkward. Fully aware of the audience’s gaze on her body, observing and observed, she asks, “So what?”

In Spencer Weidie’s the ways and means, a trio of dancers (Ashley Merker, Connor Speetjens, Sherah Shipman) slowly revolve around each other and through the space, like stone sculptures slowly coming to life. The first few chords of Phillip Glass’s Wichita Vortex Sutra float through the air before abruptly stopping. This happens a couple of times before the music continues. Similar to Glass’s music, the dance is slow to evolve and builds almost imperceptibly, yet the restraint and repetition transport you into an ethereal world. The dancers, who started in a tight cluster, slowly move further away from each other, but even as their formation shifts, they can’t escape each other. At one point, they weave in and out of each other, but no matter how you shuffle three points, they will always form either a triangle or a line. They end in a diagonal line on the floor, stuck in a loop.

In Dis.Ill.U.sion, Erin Bryce Holmes is also acutely aware of her body--not just the audience’s gaze on it, but the expectations placed on it. Holmes, the most dynamic performer of the night, brings the audience along in her journey of struggle and triumph. The piece is split between two parts: the first, sweet and pleading, is to Need A Little Sugar in My Bowl by Bessie Smith, while the second is to Nina Simone’s Be My Husband, strong yet vulnerable. Separating them is a moment of raw silence. As the percussive sounds of Holme’s body slapping against itself or the floor fills the air, you feel the full physicality of her body unashamedly taking up space. The cotton dress she took off during the first part is held in her hand and whips through the air as she spins before she tosses it to one side. Free of outside expectations, it is during this silence that Holmes’ defiant performance and stage presence challenges the audience to acknowledge her body on it’s own.

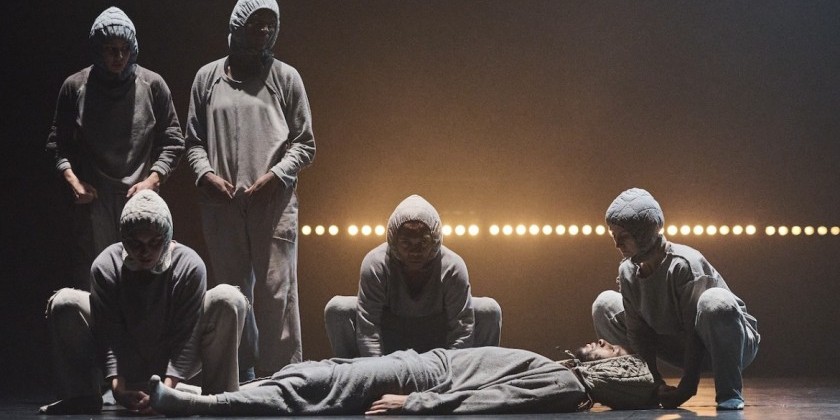

If the pieces in the first half of the program had the dancers caught in a loop or stuck in one state, Tanner Ryan’s Smock offered some escape. The militaristic first half found the dancers (Angel Blanco, Dasol Kim, Tanner Ryan) in an oppressive red light, their smocks like armor, doing repetitive movements such as touching both hands to their forehead. At one point, the dancers form a circle and gaze up, the lights change to a rainbow disco and the unrelenting industrial beat of Pussy Riot gives way to the upbeat dance pop of Robyn. As the dancers break out of their circle, you can see on their faces the pure joy of finding release in movement.

Author:

Glenna Yu

Website:

https://chendancecenter.org/about-us/news/nsapril2019