AUDIENCE REVIEW: Alison Cook Beatty Dance - An Inferno In Its Own Right

Company:

Alison Cook Beatty Dance

Performance Date:

November 3, 2017

Freeform Review:

If there were ever a proponent for the relevance of American Modern Dance in 2017, it would be me. Modern Dance is undeniably communicative of human emotion, holistic themes, and groundedness. The power of this genre shakes its audiences and spits them outside again to see the world in a vastly different way.

With utmost satisfaction, I viewed the choreography of former Taylor dancer Alison Cook Beatty on November 3rd at Ballet Hispánico. Modern Dance is clearly engrained in Ms. Beatty’s artistic tongue; her movement language appeared to stem from Taylor, Humphrey, Duncan and Graham. Derivatives from these techniques continuously appeared throughout the evening. More importantly, Ms. Beatty and her company dancers utilized Modern Dance to effectively communicate heavy, emotional topics. Alison Cook Beatty’s Modern Dance influence was successfully married with her own personal flare to create an enticing evening of dance.

During From Concept to Production: An Evening with Alison Cook Beatty Dance, Ms. Beatty presented four dances. The first two dances on the program were different variations on the same solo. Each dance was entirely different in structure and storyline. Ms. Beatty also made a point to reveal the process of each dance with the audience: she did this by offering a gallery exhibition and a Q&A session with herself, her company dancers, company manager Tony Musco, and guest percussionist Marlon Cherry.

I intentionally browsed through the gallery before the performance. I was curious to see in what context each item would be used. None seemed related to another, but I knew they would somehow tie in. Some of the items on exhibition included benches, musical scores by J.S. Bach, photographs from the 1960’s of riots and wars, a large map with black arrows and emotional words such as “rage” and “fear,” and a torn American Flag. The torn flag seized my attention.

Touched By Fire (Section 1 2001, Section 2 World Premiere) was a two-part solo that Alison Cook Beatty set on herself when she was a student at The Boston Conservatory of Music at Berklee. Originally choreographed as one section, Ms. Beatty described her reverence for J.S. Bach’s timeless Cello Suite No. 1 in G. Incorporating her own blaze into Bach’s suite, Beatty torched the studio with a wide, sweeping use of the space. She wore a brick red, open back leotard with a long, flowing skirt and tan tights to achieve the look of a leaping flame. The solo’s first section appeared more studious than the second section. Section two incorporated intricate gestures and deeper connections with the audience. Section two, set in 2017 as a continuation, was danced to Bach’s Cello Suite No. 4 in E Flat Major. All of Ms. Beatty’s movements were musical down to the last note. Her energy was peaceful as she glided through the space to Bach.

Alison Cook Beatty then danced both sections of Touched By Fire immediately after completing the version set to J.S. Bach. Her second go round, the solo was set to music by contemporary musician Julia Wolfe. Her Bach version translated her as a candle; in Julia Wolfe’s version, Beatty was an erupting volcano. Her overall demeanor was more playful, energetic, and wild. While her energy was strong in the first presentation of the solo, Julia Wolfe brought out a more dynamic quality in Touched By Fire’s performance.

“I was curious about my performance choices, when I was playing around with different types of music for Touched By Fire,” Beatty admitted in a talk-back session following the performance. “That’s why I went with Julia Wolfe. She brought out something completely different in the solo. In addition, I was relieved I could still physically perform the solo now, from 2001 to 2017!”

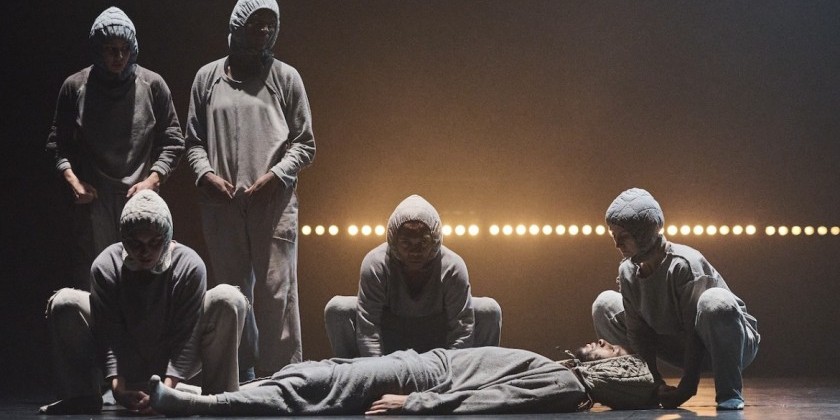

The evening’s second dance on the program was The Emotions Project (2017), a world premiere set for eight dancers in Beatty’s dance company. The Emotions Project stemmed from Beatty posing a question for many of her friends, family, and acquaintances to respond to over social media: “What do you believe the most vulnerable emotion is out there?”

Many responses included hope, shame, anger, and fear. Beatty constructed a large, tapestry-sized map with these responses written blaringly on the poster. She also pasted vulnerable images representing the responses that were taken from her home. Large, black arrows were also on her map, intending to depict how one vulnerable emotion stems into another. Dance movements were constructed by her and her dancers after conversation regarding the map.

The eight dancers’ transitions from one grouping into another depicted the map’s black arrows during The Emotions Project. They reconstructed the vulnerable images physically by how they arranged themselves in the space; virtuosic lifts, sharp diagonals, and mass groupings in organic clumps were prevalent. Employing familiar modern dance techniques, the dancers exploded in cascades of rolls, falls, recoveries, runs, and jetés. The dance opened with a contrast of brisk walks and slow, somber walks. Half of the group walked quickly while the other half did the latter.

The women wore thin, white and tan slips. Their hair was loose, and their feet were bare. The men wore long, tan pants and were bare-chested and barefooted. The thin materials they wore had an elegance, as small lace details were visible. But the lack of materials on the dancers certainly indicated vulnerability, and a lack of protection.

A scene of appearing unproctected revealed itself when company dancer Carolina Rivera became separated from the sweeping seven other dancers. The seven circled her, holding their hands in a tense circular gesture as if they were holding a ball of fire. While Carolina Rivera’s character appears depleted and desolate, her solo continues and she communicated raw desperation with technical proficiency and complete openness.

The Emotions Project did not blatantly state what the most vulnerable emotion out there is. For me, it indicated that one is not mutually exclusive.

Houston Street Hootenanny (2014) closed the program. This dance featured the full company as well as Ms. Beatty herself and guest percussionist Marlon Cherry. In this dance, I was warped into the world of the 1960’s. Eclectically dressed in denims and florals, each performer embodied a different 60’s archetype. Characters ranged from “the sexy man” to “the flower girls” to “the tough girl.” Each character interpreted his or her own challenges with living during such a changing society, for the 60’s certainly were an era of change.

Borderline shocking in this dance was a recurring prop: a tattered, mangled American flag. The “star” side of the flag was in tact, but there were several rips along the stripe’s lines. It frayed and flowed when carried through the air. It did not come across as disrespectful to be dancing with the flag. However, the state of the flag indicated that it had endured catastrophe, as with the narrative of the dancers. This flag was utilized throughout the dance as the performers twirled it, ran with it, carried it, and even wrapped it around themselves. Ms. Beatty had received this torn flag as a gift before Houston Street Hootenanny’s commission for The Joffrey Ballet School in 2014. It had been found on a railroad track, and once Ms. Beatty received it, the American flag inspired Houston Street Hootenanny. To her, the flag resonated themes of endurance and resilience within America.

I watched with fascination as her dancers reconstructed images of the Baltimore Riots of the 1960’s and the Vietnam War, when they took the space. For example, the dancers imitated “throwing back purple hearts” over three wooden benches, which were placed on stage to serve as gates. Like the process of The Emotions Project, supplemental materials (such as photographs) were used to develop the energy and aesthetic of the Houston Street Hootenanny.

Noteable about Houston Street Hootenanny was the use of music in this 2017 reconstruction. Both the original tracks were used as in the 2014 version; however, pop artists’ covers of some of these songs cut into the score and played as well. Simon & Garfunkel’s The Sound of Silence began the dance – and then when Disturbed’s cover of the same song cut in, the dance was into a fiery mood. The use of popular covers overall spurred Houston Street Hootenanny to become emotionally charged in a way that represented the “then” and the “now.”

Ms. Beatty explained that she intentionally made choreographic and musical changes to Houston Street Hootenanny in this 2017 reconstruction. She wanted to demonstrate the similarities between what people are fighting for in 1967 vs. 2017.

I vaguely wondered what sort of 60’s character I would take, if I were thrust back into this era. Would I be waiting for a lover, who just returned from the war? Would I be a hippie wearing flowers in my hair and spreading the sunshine? Would I tough it out through each day’s challenges? These characters endured it all. They progressed from slow walks to running; from trudging to skipping; from twirling to clapping, falling, rolling, and fist punching the air. The 60’s were a charged era: “this dance has the capacity to represent what happened then, and the spirit to represent what is happening today,” Ms. Beatty affirmed.

While each dance spoke of entirely different themes, fire served as my common thread between the pieces. From Alison Cook Beatty’s literal Touched By Fire – to the passionate flames in The Emotions Project – to the sparks and challenges of the 1960’s-2017 in Houston Street Hootenanny – each dance was an inferno in its own right. The dances complimented their sister pieces on the program, each contrast beautiful and blazing.

I left Ballet Hispánico heated and uplifted. From Concept to Production: An Evening with Alison Cook Beatty Dance was a terrific window into the eyes of a choreographer clearly seeking where Modern Dance can be taken next.