AUDIENCE REVIEW: "Two Completely Different Species": Lukáš Timulak’s “Masculine/Feminine”

Company:

Staatsballett Hannover

Performance Date:

Nov. 8, 2020

Freeform Review:

With its original debut in 2011, Lukáš Timulak’s “Masculine/Feminine” appears in a new, virtual format, in Staatsballett Hannover’s Rastlos (lit. “Restless"). Premiering on Sun, November 8, “Masculine/Feminine” has been available on the company’s website for the entirety of November, and will remain as such until the 30th. In terms of future showings, it appears that the company will begin live performances on Tuesday, December 9th, with tickets ranging from €21-€74 (approx. 25-88 USD), depending on the day. With that in mind, I recommend that you purchase those tickets now, or watch the performance online while it is still available; it is not something you’re going to want to miss.

The piece begins with an empty, dimly-lit stage, soon filled with the sound of a man’s voice: the monologue. Recurring throughout the piece, the monologue serves as an expository presence, revealing its book/chapter organization, and adding touches of humor betwixt the various dance segments At the beginning, he lists humanity’s greatest achievements—things like splitting the atom, venturing to the moon, and of course, reality television. He prompts the viewer to wonder: How does a woman’s brain work? Does a man’s work at all?

After this brief introduction, the stage brightens to reveal a stark, white “room” of sorts—sterile and artificial. On the back wall is a cut-out of a picture frame and a dresser, and hanging from the dresser is some sort of towel. Though not entirely similar, this design did remind me of Martha Graham’s Appalachian Spring, with its impressionistic furniture that wasn’t real, but which served as something the dancers interacted with, nonetheless.

Suddenly, a woman enters the “room,” dressed in a simple, peach dress, and her hair in a bun. The music is fun, quirky, and upbeat—something that makes you want to dance yourself. As she surveys the scene, she looks for things to clean; she checks the “dresser” for dust, fixes the “picture frame,” and ultimately portrays a sense of compulsion—she must ensure that everything is in the right place, how it “should” be. Her movements are largely a juxtaposition of sharp and angular, versus fluid and, for lack of a better term, ooey-gooey. Her jittery side is further reinforced by such behavior as: checking her watch, painting her nails, and fixing her (already perfect) outfit. With so many things to handle all at once, she briefly lapses into an explosion of erratic movement, only to quickly regain composure. Her movement pulls her in every direction, as she struggles to cope with the many tasks she believes she must complete. The monologue reassures us, however, of woman’s ability to multitask; the dancer soon finishes her work, and, once she is satisfied with the state of things, exits the stage.

Chapter 2 beings with another woman, dressed in faded green and braid down her back. The music has changed slightly, though not dramatically; the same upbeat nature is present. Though her movements are similar to the previous woman’s, they are slightly less calculated—more grounded and heavier. While the first woman was more concerned with her actions, this one cares more about her speech. Repeatedly, the woman argues with someone who isn’t there, seemingly playing out a scenario in her head. Her movement becomes twitchy, and she often throws her arms up in exasperation. Soon, a man (likely her husband, and played by a woman) enters, wearing traditional men’s work attire: a white button-down shirt, gray pants, a gray tie, and a hat. The wife continues to argue to herself, almost oblivious of her husband. The husband begins dancing with his wife, trying to replicate her movement—perhaps in an effort to understand her. While he is able to connect with her through movement, he is confused about how to approach her during her “arguments,” and ultimately exits awkwardly from the room (his rambling wife following him).

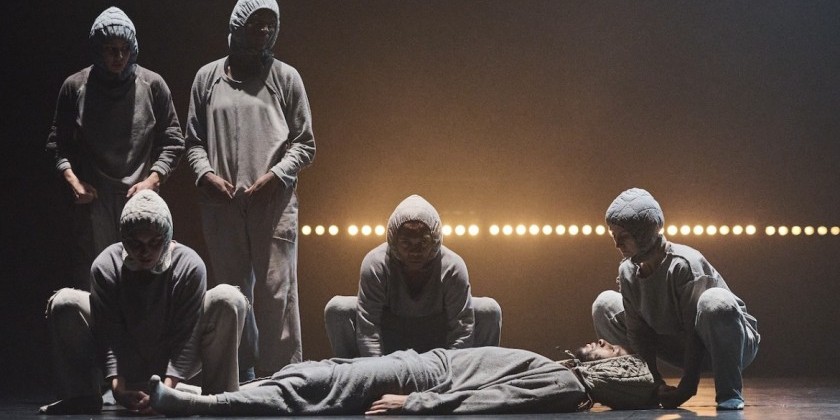

In the various chapters that follow, “Masculine/Feminine” presents the audience with such concepts as “nagging,” women’s apparent need to compete with one another, men’s vs. women’s approach to “directions,” man’s “amazing ability to think about absolutely nothing,” and of course, the need for men to be able to “shut up and listen” for once. In each chapter, the overall movement quality stays roughly the same, the chapter’s focus determining which route the dancers take, specifically. As the chapters progress, more levels are used spatially, as the dancers make use of floorwork and jumps to allow for a complete use of the space. In addition, the dancers’ movement is highly gestural and easily understood: hands pressed to temples, talking on the phone, head-scratching, reading a book—many things are conveyed through pantomime.

The climax of Book 1 appears towards its conclusion, and is seen in the interaction between three women, all dressed exactly the same (and visibly irritated because of this). The tension that rises is the result of the aforementioned need for women to compete against each other—to be superior. While they often dance in unison, the atmosphere is confrontational, as each woman clearly believes in her own superiority. The section ends with one woman standing alone, the other two having left; she lifts her chin, scoffs, and exits confidently—she has clearly won.

While Book 1 is largely centered on women, Book 2 shifts the focus to men and their behavior. Chapter 1 presents a man dressed in similar attire as the man from Book 1, this time without the hat and tie. His movement is cautious and calculated. He frequently backs away from some unseen threat; his face portrays uncertainty. Like the woman in the beginning of Book 1, this man is pulled in two directions—between one open door on stage right (the one from which he entered), and another on the opposite side. In some way, it seems as though he knows he cannot leave the way he came in, but he cannot bring himself to exit the other door either. Once he finally decides to exit, the door closes before he can leave.

The subsequent chapters present various other men in a way similar to the women in Book 1, showing primarily their behavior alone, as well as their interactions with women. Perhaps the most humorous (and shortest) section comes in chapter 3, with a man who sits in a chair, alone, in a spotlight. He does nothing but stare blankly at the audience. This, coupled with sadder, more somber music (unlike any of the piece’s other sections), gives the impression of loss—that this man is dealing with unimaginable pain. This assumption is subverted by the narrator, who informs the audience of man’s ability to, again, “think about absolutely nothing.” The music quickly stops, and he exits the stage.

In viewing this piece, I came to realize the overall similarities between the men and women being portrayed; yes, they each had their own stories to tell, but their quality of movement, and the choreography itself did not lend to any supposed distinction between the two. This was further emphasized by the casting; though I noticed it in Book 1, I did not realize, until the end of Book 2, that various roles were given to the opposite sex: that is, any women shown in Book 2 were actually played by men (and vice versa for Book 1). This was made clearer in the final bows, as it showed Book 1’s cast to be entirely female, and Book 2’s to be entirely male. In this way, Timulak was able to reinforce the idea that there is nothing inherently different about men and women. While their roles in society have been different, anyone can play them, and convincingly so. Though this piece was choreographed in 2011, its message is extremely pertinent today, and asks us all to wonder: What makes something masculine or feminine? (and more importantly), Who cares?

Author:

Jacob Blank

Website:

https://www.staatstheater-hannover.de/de_DE/mediathek-staatsoper

Photo Credit:

Bettina Stöß