AUDIENCE REVIEW: Radical joy and solidarity at 7MPR

Company:

7 Midnights Physical Research

Performance Date:

Sunday, July 16, 2023

Freeform Review:

Studio 3F at Arts on Site is an intimate space. Nestled three stories above St. Mark’s Place in the East Village, the seating is not only in-the-round, and it’s not just the warm lighting–for me, the particularly narrow benches pressed up against the brick walls on either side make me feel like I’m leaning in towards the dancing space, almost like I could spill over into it.

For emerging dance artists in New York City, there are a number of open platforms for presenting new work. 7 Midnights Physical Research, or 7MPR, founded by Artistic Director Jiali Wang and held in cozy 3F, is unique in its commitment to dances that explore one or more of seven sociological topics: class, education, ability, sexuality, race, age, and gender.

This particular performance, Fifth Midnight, on 7/16 was a solidarity event entitled “Immigrant Artists Matter.” During the post-show discussion, Wang shared their experience–that immigrant artists work incredibly hard (citing visa challenges as an example), and it’s important to bring them together in creative community. They remembered a dance professor saying, “when we dance, we have to think about what we’re doing, and how it relates to what’s happening in the world.”

The evening opened with a solo by Wang danced to spoken text detailing the premise of 7MPR: movement artists provide a unique response to contemporary social issues. Wang’s limbs were linear, but her trajectory was swirling, toggling between direct intentionality and rigorous abandon. Always, however, satisfyingly contained.

After Wang’s opening dance, “A Pathway to Silence” (an excerpt from a larger work, “Songs of the Sea”) by Ho-Shia Aaron Thao performed by dancers of Hudson Ballet Theatre commenced with its immediate panicked, sorrowful tone. Four dancers (Hayley Clark, Bethany Kellner, Juliet Mazzola, and Barbara Tosto) performed undeniably beautiful contemporary ballet with rich, nuanced musicality and rigid intensity. This dance was unrelenting–as were the minimalist piano and strings tracks–and incredibly fast. Unified by form, the dancers conveyed loss, grit, and perseverance.

Natalie Long’s solo work “Unrequited Fruitbowl” began, but then was quickly interrupted by Long herself, who removed a paper from her white dress pocket and quickly read aloud several quotes by immigrant artists in apparent solidarity with the evening’s theme. They moved on–not as if nothing had happened, but matter-of-factly nonetheless–circling the space with increasing speed and then halting, as if having been fixated on something of immediate necessity before jolting back into regular consciousness. In a floorwork sequence, Long’s legs were weighted and spent, splaying and contorting with ease and exasperation. Stumbling, faltering, and etching black cross-hatches on the corners of her mouth and inner thighs, she seemed to be clinging to–and claiming–power in surrender.

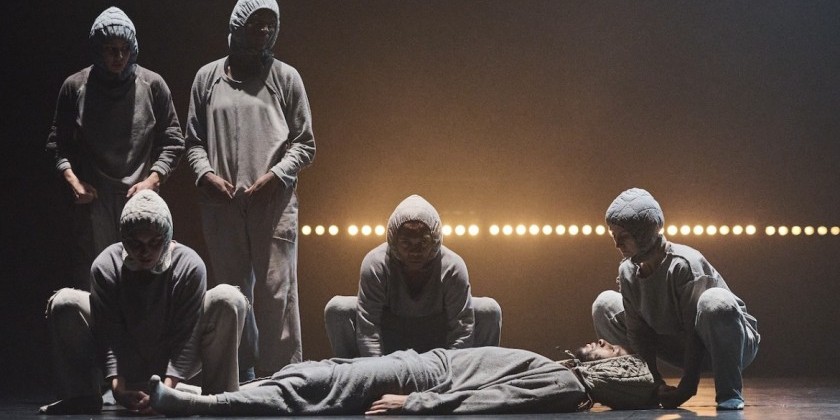

“Ardhanarishwara” by Sahasra Sambamoorthi was brilliantly embodied. Sambamoorthi and duet partner Ankita Khanna seemed to have a wealth of secrets between them, the audience privy to a select few. They enlivened the space in a distinctly clear and specific work that, through the classical Indian dance form Bharatanatyam, conveyed the sacred hymn Ardhanarishwara Stotram which “praises Lord Shiva and his consort Parvati in their combined form… telling a story of the divine union of masculine and feminine energies.” The dancers masterfully shifted their embodied energies as the hymn unfolded, and their movements were deeply intentional and specific–down to the gaze. Their storytelling was clear, direct, real, and captivating, and in the post-show discussion, an audience member commented on how they could feel this particular performance in a truly visceral way.

Devyn Ciccio, Madi Gibson, Daniella Hernandez, and Melissa Jones improvised with awareness and intensity in “Current Events” conceived by Philip Ellis Foster. The dancers repeated peculiar gestures, like hands clutching lower backs, inverted shoulders, and crossed wrists, moving carefully at first as if to avoid alarming one another. The work felt dark and nearly apocalyptic. The dancers sporadically took physical risks, slicing and tossing limbs very close to the edges of the space, and observed one another for long stretches of time. They found flow, gentle touch, and sweetness in moments of contact that contrasted the haunting tone they created together, especially as the accompanying bare piano notes became increasingly warped. They embodied vigor–in risk, observation, and waiting.

A truly enlivened duet entitled “Episodes of the Soul-RECOVERY” by Zazel Chavah O'Garra performed with Wendy Ann Powell was a dynamic return from intermission. Exclaiming, “immigration!” and “why are you looking at me like that?” the dancers embodied a rich vitality. Utilizing a combination of seated and standing movement, they created elegant conjoined lines. Embraces and clasped hands matched the intensity of the opening sound, which abruptly changed to an upbeat track halfway through; the dancers’ tone shifted instantly to match it. One dancer helped the other remove their leg brace, a cane was tossed aside, and in an exhibition of real, honest joy and strength, they danced with conviction to the beat while the audience clapped along. The work concluded with more exclamations, some repeated– “immigration,” “why are you looking at me like that?” and some new– “...freedom? America…?” with a questioning tone. Radical joy, to be sure, while decisively acknowledging the painful, contradictory, and confusing circumstances of the present socio political moment.

“Compass” by Srinidhi Kundur was glimmering, exhibiting strength and joyous perseverance. With a clear tone of wonder and curiosity, four dancers (Sucheta Bose, Aneri Desai, Srinidhi Kundur, and Sadhana Subramanian) began in a compass shape, abandoned it, and returned to it again and again. Stylistically alluding to traditional Indian dance forms, a pulsing, resilient feminine strength grew in intensity as the dance quickened. It was effervescent, and impressive in speed and in its clever use of form.

Sally Butin and Emily Van Duinen’s “Not Funny, Hysterical” was captivating and smart. They took the space with authority, which rendered their attire–long, ruffled, and floral patterned dresses–a clear poetic contradiction. The title and costuming alluded to historical witch-hunts, but again, the clever choreography was the strongest storytelling element of the work. They wandered in tandem with an eerie, strange sense of yearning for something–possibly one another. A white bench tipped to one side supported distinct and arresting imagery. Van Duinen pulled the bench over her, so its legs rested on either side of her neck. Later Butin laid across it, her wavy hair tumbling down for Van Duinen to braid (a sweet moment of care) and then admire momentarily, chin resting in hand, before both dancers spastically abandoned the gesture. Watching them repeatedly find one another and separate, surrender and lean on one another before parting just as intensely, all while utilizing their evident virtuosity, I wondered about hysteria, femininity, and queerness.

“9 Tales of a Bitch” by Sunhi Willa Keller was an expansive exploration of feminine Asian-American identity and sexuality. Giggling flirtatiously from behind red fans, the four dancers gossiped in a chorus of, “I heard she just likes the attention,” “she’s a bitch,” and in a sharp change in tone, “she’s a soul sucker,” at which point they flipped their fans revealing black on the other side, hinting at darker subtext. Later, they formed a writhing pile on the floor, rolling around the space, still giggling. The work bounced casually between hyper-feminine sensuality and disturbing imagery (like hair-biting), perhaps both were intended to alarm the viewer–I was reckoning with my own responses as the work unfolded. The tone changed suddenly and dramatically when the dancers expertly morphed into fierce, terrifying monsters. This instantaneous shift, from hyper-feminine persona to aggressive creature, felt like intelligent commentary on how identifying with femininity while claiming physical space might feel confusing and contradictory. A patchwork of giggle, monster, and seduction, “9 Tales of a Bitch” was truly smart, and an undoubtedly strong work.

Jiali Wang’s closing dance, “No More Playing,” was a lighthearted and centering conclusion to the evening. After setting their own lights and sound, Wang began a direct, rhythmic, compact, and efficient set of gestures moving towards a plastic gray storage tub. When they approached the box, they gingerly lept inside and settled with a few bounces. Her tone was mildly humorous but still focused, and her movement creature-like, but always swift. There was curiosity, but no uncertainty. According to Wang, the box represents a space where they can “take a break from the stress of life,” particularly as an immigrant artist.

Concluding this playful yet assured work, Wang seamlessly transitioned into earnestly inviting the audience and performers to join them in a final joyous dance. 7MPR always ends this way; choosing community and celebration through and despite the often heavy subject matter roused by the presented work.

Author:

Hannah Lieberman

Website:

hannahbethlieberman.com

Photo Credit:

“Ardhanarishwara” by Sahasra Sambamoorthi; photo by Renfang Ke