AUDIENCE REVIEW: Laura Tuthall in One-Woman Show "Oxygen"

Company:

Laura Tuthall

Performance Date:

2/22/20

Freeform Review:

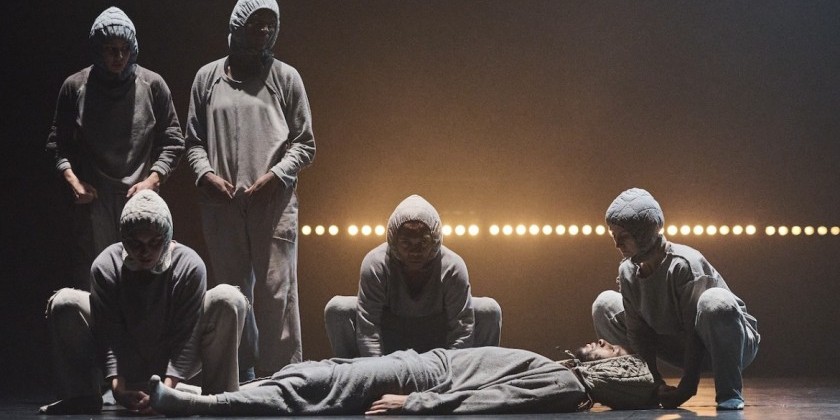

Halfway through her one-woman show Oxygen, Laura Tuthall lays on her back on the floor, arms spread from her shoulders in a T position, knees bent with feet planted on the ground, lights dimmed except for the spotlight on her still body. An audio recording of Tuthall reading Silent Snow, a poem written in the early 20th century by Tuthall’s great aunt that she discovered while going through old family heirlooms, plays in the background.

The poem is a sestina, a nearly impossible form comprised of six stanzas of six lines each followed by a seventh stanza, called an envoi, of three lines. The lines of each of the first six stanzas end with the same words in an order that is rearranged for each stanza, such that the six words are repeated throughout the poem. Often, the 6 words are chosen for their connotative flexibility – their ability to mean different things depending on their linguistic context. In Silent Snow, for example, each line in the first six stanzas ends with the words dawn, snow, tree, rose, lie, or day; sometimes, rose connotes the flower, and other times, the past tense of the verb to rise. Thus the form provides an eerie echoing quality that suggests mutability, impermanence, and the inevitability of change amidst seemingly static, or “status quo,” conditions. It is a tricky form, one that relies on the complexity of language to convey its multiple meanings; one that embodies the inherent multiplicity of subjectivity to construct a many-layered whole.

Watching the entirety of Oxygen through this formal lens provided a guiding structure for the ambitious, far-reaching show. A preliminary analysis of the piece might describe Tuthall’s virtuosic and multi-disciplinary artistic accomplishments: she’s simultaneously a lyricist, vocalist, musician, dancer, actor, assembler, designer, reader, conceptual artist... this preliminary analysis might also explain content: how the lyrics and movements broadly examine, critique, and/or narrate experiences of disability, environmental destruction, political power structures, medical violence, sex, gender violence, mental illness, intersectionality, capitalism, loneliness, individualism, ancestral lineage, and social responsibility. This manner of describing and cataloging, however, is incomplete. Here, the sestina offers a framework for describing the relationship between these components, which is where the work derives much of its meaning - the way these various themes and expressive components affect each other, and suggest additional meaning where literal translation ends.

Oxygen begins with a ten-plus-minute tour-de-force in which Tuthall’s jazzy, sultry, sometimes edgy voice expertly traverses the far-reaching landscape of the titular song; she flows from low growl to high pitched vibrato in the span of two words as she seamlessly accompanies herself on the piano. The lyrics describe a disjointed narrative, one not informed by linear time but rather organized around related themes. Many of the metaphors relate to the physical body, blurring the line between “real” and “imagined” (and perhaps interrogating that dichotomy altogether). Got old blood in the brain/sticking on that same refrain, Tuthall croons, both denoting a physiological experience and connoting its psycho-cognitive equivalent. Throughout the song are references to creation and destruction: here we go again/weaving time from broken threads, and later, can we construct/a new better us, and still later, should we construct/and welcome who have destroyed/…or/should we burn the whole thing.

After this opening song, Tuthall rises from the wheelchair at which she sat playing piano and begins moving through the available space as her recorded voice accompanies with another original piece. Her physical movements, like the sestina, are circular and repetitive yet forward-moving, mixing swingy, loose limbs with sharp, shagged punctuations. Tuthall’s background in ballet is achingly evident – her lines perfectly rounded, her grace impossible to disguise.

But this failure to disguise isn’t really a failure; instead, watching Tuthall embody this balletic technique in a way that serves both her own needs and the needs of the show suggests a wholly new – dare I say radical – approach to the form. Many dancers, particularly those of us alumni of traditional western forms including ballet, are taught to mask pain, to hide injury, to “push through” – language that closely mimics and mirrors that of capitalism (“the ends justify the means”; “goal-oriented”; “survival of the fittest”; etc.). To perform as a dancer shifting between wheelchair, cane, and unassisted movement, as Tuthall does in Oxygen, directly challenges ballet’s centuries-old tradition of hyper-valuing a very specific, hyper-feminine, lithe, nimble, “easy” physical aesthetic that dismisses bodies and experiences that exist outside the realm of what western medicine describes as “healthy” or “able.”

On her website, Tuthall identifies as a “disabled interdisciplinary artist, activist, and educator” who received a diagnosis of hyper-mobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome - a complex and underdiagnosed connective tissue disorder - halfway through a BFA in contemporary ballet at Boston Conservatory. In the wake of the diagnosis, she shifted her focus to improvisational dance and collaborative performance and now aims to center “disabled and neurodivergent voices” in her creative and somatic work. What this means for Oxygen is that Tuthall shows her body and all its dis/abilities unmasked, unwilling to hide the reality of her – and many others’ – embodiment.

If ballet’s call is to cast the illusion of beauty, youth, and ease, Tuthall responds by turning the technique on its head, coupling elegant extensions with gestures describing, amongst other traumas, self-harm and sexual violence. Most notable, though, is the way Tuthall transitions between dancing un-assisted and using her wheelchair or cane. This “unveiling” is both a direct challenge to the dance world’s pressure to hide pain and disability – or broadly, that which is mortal – and a direct challenge to ableist assumptions about permanence; that a body is either “abled” or “disabled”; that such categories are or should be recognizable to the outside eye; that identity is static. These assumptions contribute to an “othering” that allows the able-bodied dance world – and world-world – to continue status quo without making much of contemporary life accessible, because those unable to access things in the “normal way” are inherently “different” and “apart.”

Oxygen suggests a liminality that threatens these assumptions. To see Tuthall shift from chair to cane to her two feet and back again suggests a more fluid reality, forcing the audience to confront our own mortality: if her body can hold all these truths, so can ours; if her body can allow ambulation and also require mobility aids, so can ours. And what an auspicious time to communicate such an experience. The show premiered in Manhattan in late February, barely two weeks before the whole city began shutting down in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic, which is still dictating daily life throughout much of the country (and many parts of the world), is forcing many folks to consider questions of physicality, illness, mortality, ability, danger, and accessibility in ways never required of “able-bodied” people before. Tuthall’s fluid transitions between various mobility tools are simultaneously aesthetic and physically required. She needs to use canes and wheelchairs to perform; they are not an apology or “statement,” they are integral to the piece, and they suggest a kind of flexible way of being that may be particularly instructive to the non-disabled community suddenly floundering amidst the unknowns of this particular moment in history.

In this way, Oxygen is a kind of holistic investigation into the dialectic between permanence and impermanence. In the context of psychology, dialectic describes a tension between two seemingly opposing but simultaneously occurring truths; i.e. My parents are good people and they also fucked me up, or I’m craving connection but feel anxious when around people. The dialectic between permanence and impermanence permeates Tuthall’s show, in the form of tensions between themes of loneliness and community; subjectivity and collective narrative; location and dislocation; power and submission; fear and anger – tensions that, like the words in a sestina, may feel static even amidst obvious mutation and change.

These tensions are visible in the language of the poems; in the vocal range of Tuthall’s singing, and in the stylistic and physical breadth of her movements. Near the end of Five Years: Excerpts, the third and final poem-song in Oxygen, Tuthall sings, why blame what is green?/What grows from graves,/from the sacred space/between loss, limitation, and dreams? thus casting a rhetorical shadow on the infamous “flower-growing-through-the-sidewalk-cracks” image. The song suggests that the dialectic between destruction (capitalism, greed, etc.) and love (creation, life, etc.) that seems to dominate not only the whole piece but also our current socio-political reality, may be itself a falsehood. The resulting spaces (literal, creative, intellectual) between the performance and the world on which it critiques become spaces for possibility. We are not guaranteed an optimistic conclusion after destruction, but we might collectively weave something new to emerge from the depths. I visualize this “something new” as connective tissue, perhaps, between the oppressive forces shaping our global reality (various economic and social-isms) and a more just, sustainable network of people caring for each other and the land.

What a cloying metaphor! – connective tissue that represents connections between the many themes in Oxygen performed by an artist with a connective tissue disorder. But the linguistic tool is too apt to ignore: connective tissue is a complex network within the body that brings our various systems and parts into a (somewhat) cohesive whole. A disorder of the connective tissue suggests a dis-junction, a scattering, a dis-location. By mixing poem, song, formal artistic tradition (sestina and ballet), improvisation, family history, and anthropological inquiry, Laura Tuthall creates a very clear conversation between the dis-locations in her body and the dis-functions caused by capitalism, abusive power, and environmental degradation. The resulting effect of these layered meanings and mediums is a texturally rich, layered web of duality that resonates on a visceral level with the questions many of us are asking ourselves these days:

How did we get here?

What do I do with this mess?

Is there another way?

Learn more about Tuthall and her work at www.lauratuthall.com.

Author:

Leigh Sugar

Website:

leighksugar.com