AUDIENCE REVIEW: "Fase" - Masterfully performed phases that form a whole haunting portraiture

Company:

Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker

Performance Date:

July 9, 2014

Freeform Review:

Kristin Chang, Dance in the City (Barnard Pre-College Program)

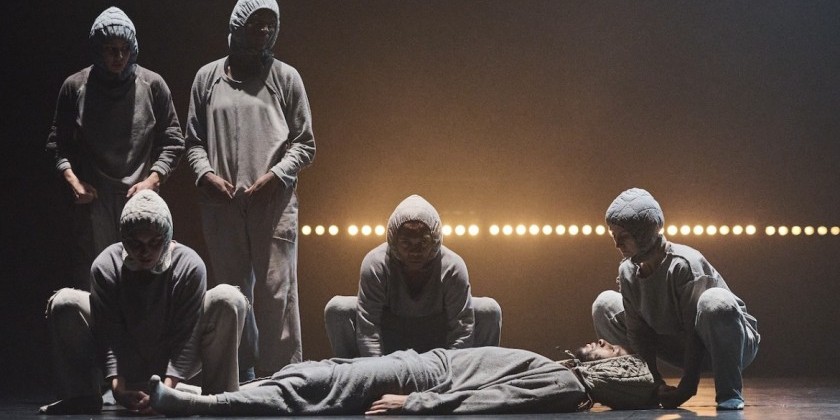

In an era where so much people-to-people communication no longer necessitates the physical bodies of people, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s revived Fase at Lincoln Center truly resonates.

In Come Out, the most dramatically lit of four movements, dancers de Keersmaeker and Tale Dolven are illuminated by lamps, their shadows refracted on a panel against the right wall of the theater. The space becomes occupied by the noncorporeal, a stark and haunting presence that probes the audience: the experience is intense in the best way possible. de Keersmaeker almost demands that we ponder what it means to interact as human beings. Their two bodies never physically touch, and yet their immaterial impressions constantly converge. A subconscious collision.

Watching Piano Phase, which also explores the idea of human contact on a separate plane, reminded me of the long subway ride to the theater, where dozens of people are sealed knee-to-knee, never quite seeing each other. And that is what the best dance can do: create a sense of deja vu and vertigo as you realize that you are living and breathing in the world of this art. In Piano Phase, dancer Tale Dolven is in breathtaking form, literally: in moments of pause, her intake of breath pours air through her body and expands her ribcage. The resulting spring-forward movement, just a simple pedestrian step, seems to place her entire being at stake, and the audience is effectively jarred out of their reverie.

Cyclical swinging of the arms is punctuated by the two dancers’ dramatic breaths and hissing throughout the dance: their audible breathing successfully reveals their vulnerability while simultaneously contributing to their mechanical movement.

In one instant of Piano Phase, de Keersmaeker briefly wipes her nose with her left hand. This startlingly pedestrian gesture reminds the audience of the dance’s embracement of the everyday. de Keersmaeker choreographed Fase in 1982 to Steve Reich’s looping music, and the dance has been previously performed in a concrete garage, where the choreography conversed with a close-knit standing crowd in London. Now, even on the pedestal that is Lincoln Center, there exists that same intimacy.

Then the dancers dive back into their discipline. Violin Phase is the most traditional of the four pieces, at least in terms of traveling patterns. de Keersmaeker pivots and hops and lifts her skirt as if she were swing dancing, and the playful gesture is another intimate movement.

My companions and I were stunned to learn that de Keersmaeker is 58 years old. Of course we’d divined that the dark-haired dancer was older than the fair-haired Dolven, but we could hardly comprehend that somebody who could be considered “past her prime” could resist lethargy and slice the air like an exacto knife. In the final movement, Clapping Music, the uncontrolled near-flailing of her upper body made Dolven appear, in comparison, more hermetic and reserved.

Throughout the performance, there was always that aural tinge of something being there. de Keersmaeker achieves more than just sharp line and precise choreography: she constructs an atmosphere with her limbs. Like the haunting silent movie of shadows becoming one, what was there was something internal made external for the audience. As I walked out of the theater into the dense, post-rain night and saw my own shadow emerge by the light of a window, I swung my arm out just to see. It moved with me and away from me, simultaneously: de Keersmaeker’s choreography manages to portray isolation and connectedness all at once, the constant polarity that dominates human life.