AUDIENCE REVIEW: Dance Drama/ Anabella Lenzu- Ilusiones De Percantas for Art in Odd Places

Company:

Dance Drama/ Anabella Lenzu- Ilusiones De Percantas for Art in Odd Places

Performance Date:

10/05/2012

Company / Show / Event

Dance Drama/ Anabella Lenzu- Ilusiones De Percantas for Art in Odd Places

Performance Date

10/05/2012

Venue / Location

Union Square

A bit about you:

(your occupation, the last time you moved, your website, etc.)

Kate Ladenheim; Artistic Director of The People Movers. www.peoplemoversdance.com

Freeform Review:

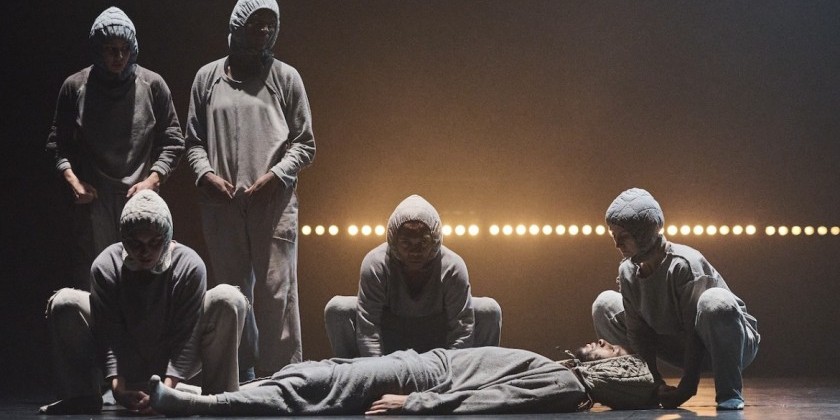

I’m standing in Union Square, and a woman approaches me. She is dressed as a colorfully mismatched maid, and she carries around a broom and a feather duster. Strangely dressed people in Union Square? Not really a shocker. However, this woman comes up to me, points to the guy standing next to me, and asks, “You like him?" I laugh. "Me neither," she says. "I’m looking for a boyfriend.” She points to some other women in front of the statue, all dressed in their own very particular vintage outfits. “We’re all looking for a boyfriend.”

The maid and her vintage-clad compatriots are part of Anabella Lenzu/DanceDrama, a NYC based dance company participating in the Art in Odd Places Festival. One of the goals of the festival is to bring art to people who don’t usually get to see it. In this sense, Lenzu’s choreography was a perfect asset to the program: it was incredibly accessible, humorous yet poignant, and Lenzu’s charismatic work certainly grabbed the attention of the passing crowd. More importantly, however, Ilusiones De Percantas brought up several important questions about women and their role in today’s society as well as the relationship an audience can have with art and the performers creating it.

At first I have to admit I was affronted by the idea that all women are looking for a boyfriend. I asked Lenzu as she was making her rounds why she wanted a boyfriend. She replied, “I want a man to take me out of this life as a maid.” The feminist in me cringed. Why, exactly, do you need a man to take you away?

In the historical context of Ilusiones, however, this would be an appropriate feeling. The piece is set in Argentina in the 1920s/30s, and each of the women have their own particular stories inspired by the lyrics of traditional Argentine tangos. The tangos were completely lost within the din of Union Square, but the performances conveyed their essential meaning to the audience. Their fantasies, mixed in with anger, desperation, and the pain of realizing one’s true situation, gave way to multi-faceted performances—these were not all superficial, one-sided women, but artfully layered, psychological explorations.

The first soloist, Tina, was a young woman in her early twenties who wants to get married. Her solo begins in a dreamy state: Tina holds a bouquet of white flowers to her heart and shyly looks at the audience. As the solo progresses, she gets more and more angry and desperate. She stomps her flowers on the ground, pulls out a cigarette and violently sucks and inhales, and runs up to the audience, demanding, “where is he?” She reminds me of Charlotte from Sex and the City, a girl who plays innocent and demure when she is actually quite desperate, pushy, and manipulative. Though very well performed by Lauren Ohmer, Tina was to me the most archetypal character. The marriage-obsessed, crazy girl will be around in every age, but she will never escape the bounds of cliché—especially because Tina’s frustration appears to be entirely self-inflicted. Rather than society impressing upon her that she needs to be married, Tina’s dreamy attention to her bouquet of flowers and the cigarette stress seems to come from within rather than without.

Tina, however, serves as a good introduction to the other more densely psychological solos. The next dancer, Palomita Blanca, comes forward. She is a slight girl in a wedding dress. Lenzu scoffs at the crowd, “she is the youngest one, and the first to get married!” Palomita (performed by Mary Elizabeth Fenn) keeps her head and eyes down, and looks fearful and downtrodden. She makes a few feeble attempts at giggling, or flirting, playing with a red scarf that she keeps tucked in her sleeve. She begins laughing oddly, and the other girls start laughing at her too. She awkwardly giggles along at first, but it becomes apparent that the laughter of the others is not playful, but abusive—this character element becomes even more apparent when later on in the solo slaps herself. Perhaps Palomita Blanca is looking for a man to take her out of an abusive relationship. The red scarf, a bloody symbol that she keeps tucked away or shyly displayed, demonstrates this idea of hidden strife—and also that Palomita is hiding a dark and mysterious secret. I’m still not entirely certain what it is.

Then Margot—the lady of the house (played by Liz Gorgas)—steps forward. Her dress and platinum blonde wig remind me of Marilyn Monroe. She initially is playful and flirtatious, but like Tina, she slowly descends into stress and anger. Also like Tina, I felt that Margot was a bit predictable; the difference being that her situation was entirely inflicted by others. The angry, tortured prostitute is of course a story that we have heard before—However, with Margot we can see the struggle between what is expected of her (how she is supposed to act) versus her true feelings about her situation. Her movements suggested that she was fighting back in some way.

Finally, Lenzu as the maid Pipistrella had her turn in the spotlight (though arguably, she was always in the spotlight—Lenzu’s other soloists didn’t quite stand up to her passion and charisma). Pipistrella fantasizes about the love of her life sweeping her away—quite literally, as Pipistrella makes the broom and duster into a man that she tangos with, kisses, and romps around with on the floor. It is delightfully audacious. The humor makes her character seem light hearted, but Pipistrella is stuck too—she is limited in what she can experience by her socio-economic role. The fantasy may be hilarious, but it is also indicative of deep-seated dissatisfaction.

The strongest uniting factor amongst these women is just that—dissatisfaction. The search for a boyfriend is simply the symptom for a much bigger problem: all of these women display an incredible amount of disappointment for the current life they are living and the standards that they are expected to uphold—and they want a way out. These standards are inflicted either by society (in the case of Margot and Palomita Blanca) or from within (Pipistrella and Tina).

Though Ilusiones de Percantas has a very strong historical context, this piece has a particular strength today in respect to the U.S.A.’s current political battle. The struggle of women to be treated with equal consideration and respect has come up so strongly against ignorance, stereotype, and misinformed zealotry. Women today feel similarly stuck—disappointed that even though we have come so far from where Margot, Tina, Palomita Blanca, and Pipistrella were, we are still victims to those who would pigeonhole us into similar societal roles. As Pipistrella said to the audience during the performance, “You may see something of yourself in them [the soloists].”

All of the characters gave performances that were poignant, fully present, and committed—clearly, Lenzu has high standards for herself and her performers. Yet even with this accessibility and the generosity of the performers, the audience that gathered around the spectacle kept itself at a safe distance. Lenzu, part performer and part audience shepherd, had to corral the spectators in closer to the performance. She seamlessly and charismatically meshed this process with her character, dusting people off, flirting with the surrounding men, and handing props to audience members. I found it particularly interesting that the audience imposed the audience/performer barrier, viewing at a distance some weird spectacle even when the performers so wanted to be involved with the audience. This is indicative of a bigger problem with art: simply putting art in odd places does not necessarily mean that people will be able to interact with it on a more personal level—modern audiences seem to still want to kept their art at a safe distance from their “real” lives. How interesting—these women who are so real, so layered, and impossible to compartmentalize into one personality have in fact been simplified and compartmentalized because of the resistance of the audience to actively participate.