AUDIENCE REVIEW: ABT Giselle: Copeland's Dramatic Strength

Company:

American Ballet Theatre

Performance Date:

May 15, 2018

Freeform Review:

Misty Copeland is subjected to a lot of negative criticism in the press, and I don’t really know why. Yes, I’m sure being the first African-American female principal dancer at American Ballet Theater comes with a more unforgiving, oppressive and scrutinizing spotlight than normal in the highly competitive and idealized world of ballet. But are all of these criticisms warranted? Yes, Misty herself talks openly about the steps she struggles with: we all know about her 32 fouettes as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake, and the ensuing arguments about her right to be a principal dancer with such an illustrious company. And yet, here she is. And I don’t think she is here because of the color of her skin, some nod to the affirmative action laws of the 1960s. I think she is here because of her grace and skill as a dancer, not merely as a technician, but as an expressive performer. After all, is that not what we come to see? Do we not come to be moved by the totality of a performance and the nuances that each dancer brings to his or her roles?

With a demure, downcast head in the first act, Copeland’s Giselle is a testament to her acting skills. She is innocent but not dumb, naïve but not immature, psychologically fragile, or overly vulnerable. Her giddiness and youthful joy are infectious, her ability to be terrifically in the moment, reacting to each turn in the plot, brings freshness and life to a familiar story line. This Giselle is an ordinary girl-next-door in love with a boy. Perhaps that is what some of her detractors either do not understand or do not like about her dancing- that she brings a ‘realness,’ an ordinariness, to the overly unreal idiom of classical ballet.

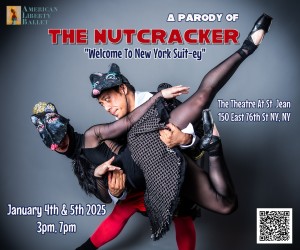

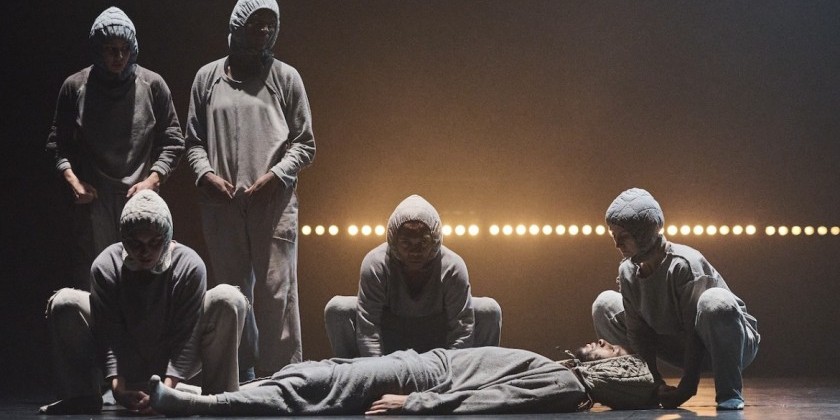

Herman Cornejo, a commanding presence at all times, dances her lover, Count Albrecht, with just enough arrogance and bravado to make him loveable, and in the second act, the perfect blend of remorse and grace to make him forgivable. The chemistry between Copeland and Cornejo is palpable and evident in the way they embrace, the way he touches her in their pas de deux, even the way he escorts her onto the stage during the curtain calls. Alexei Agoudine as Hilarion, a character often portrayed as a countrified boor who is merely a hindrance to the lovers, dances the role with moving sincerity and honesty.

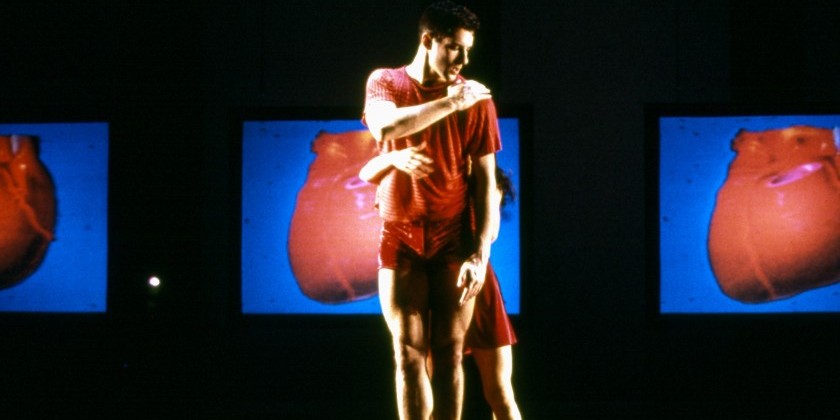

Copeland’s strength as a dancer is surely her dramatic side. I love her exuberance, her joy in movement that she relishes and shares with audiences, her youthful excitement and commitment to character and mood. She is a lyrical dancer, her upper body supple and yielding like the long branches of a willow tree in the wind. Her lines are clean and long, and her tight first position in chainne turns, her winged feet moving so precisely and quickly like the needle on a sewing machine, always thrills me. Technically, Copeland’s dancing is good. Perhaps not as virtuosic as some of her principal counterparts and challenged in the most difficult steps, but for me at least, this is not a problem. Ballet has changed quite a bit over the years. For example, in the 1970’s, a 90-degree arabesque or a developpe in second hovering around 120-degrees was the norm. In fact, I was told by a few Balanchine ballerinas I trained with that he considered too much flexibility to be vulgar. Today legs nearly brushing the ears in extensions to the side are considered normal. The amount and speed of turns and height of jumps have increased as well. And I understand that everything evolves and that is a normal and necessary process. But we must not forget what dance is, and what it is not.

First and foremost, dance is an expressive art. It is a means to express stories, emotions and ideas through movement and gesture. It is not gymnastics. It is not the circus arts. It is not merely tricks to thrill an audience in some sort of instant gratification, overtly obvious, easy to digest manner. It is an art, a technical art of increasingly high standards, but an art nonetheless. So therefore, let us appreciate, not judge, our artists based on their ability to move us, stir something deep within us, call to us, challenge us. It does not bother me that Misty Copeland struggles with 32 fouettes or other such variations, or that she changes them, not unlike other principal dancers in other companies, by the way. No one step defines a dancer. Technique is the science to the art of expression, and there are many young dancers training today who can pull off complicated steps without possessing any other outward sign of artistry. It is the execution of movement, the phrasing choices a dancer makes, the seemingly unimportant and easy to gloss over transitions, that make a dancer great. Not some 122-year-old trick that speaks nothing to an audience save for the emotion the dancer puts behind it.

I appreciate Copeland and Cornejo’s expressive interpretation of their roles in Giselle, their passion and artistry, and the joy I felt watching them dance. They deliver great gifts as they bring their own unique stamp to these signature roles and I look forward to seeing how that interpretation evolves with time.

Author:

Cecly Placenti

Photo Credit:

Misty Copeland and Herman Cornejo in "Swan Lake." Photo