AUDIENCE REVIEW: Lessons Learned from Catherine Galasso + Andy de Groat

Company:

Catherine Galasso, Andy de Groat

Performance Date:

December 13, 2015

Freeform Review:

Header photo by Lois Greenfield

When my aunt invited me to see “get dancing” at Danspace Project in St. Mark’s Church, I took a skeptical glance at the black and white photo on the postcard. Catherine Galasso was restaging Andy de Groat’s dances from the 1970s with a mixed cast of his original performers alongside newer ones. Sure my aunt’s 70-year old friend was performing, but I had never heard of de Groat, and I tend to loathe historical preservation pieces. To me they represent what’s holding American contemporary dance back— the parade of institutions presenting Graham, Taylor, Cunningham, year after year is boring, and also seems to miss the point. We spend so much time enshrining our “golden age” of modern dance that we’ve forgotten to support innovation in our form. So I penciled this show in with reluctance.

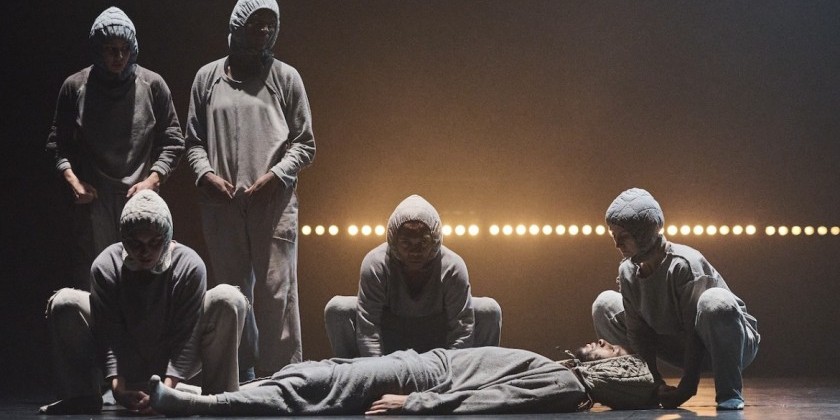

The evening opened with “Rope Dance Translations”, a black and white film, projected on the sanctuary wall. Four dancers quirkily arranged a series of knotted rope loops, and slowly began to revolve. As they gain momentum, the concentric circles of their apparatus envelope their spinning forms. I was entranced. The simple poetics of revolving geometry was not only fascinating, but also familiar. Spinning was a skill I’ve honed as a dancer with Jody Sperling/Time Lapse Dance, and through performing Laura Dean’s work in college. Side note: has anyone written a paper investigating the trends of spinning in American modern dance from the 1970s? Suddenly this was historical dance in conversation with my own story.

Intermittently, a dancer would appear in a spotlight on stage, rope circles in hands, spinning live alongside the film. These dances had been performed here, in this very church forty years earlier. I felt like ghosts had literally been conjured back into the space, spinning before my eyes. Some were young, others were white-haired, but they each created their own presence from the echoes left in that cavernous space.

I, too, have performed in St. Marks Church and it is always magical. But this was something more. Watching dancers both my age and much older didn’t cause me to compare spinning virtuosity (they all had that) but rather to reflect on what those original performers must be feeling to retrace their own steps on that sacred stage. How many times have I worked months, pouring my passion into a show that only had two performances? What would it be like to wait forty years to have another chance?

The dialogue between youth and experience became more apparent as the show flowed seamlessly into the next piece, “Get Wreck”. The dancers seemed to make their own movement choices, based on personality: my peers gamely jetéd across the floor, while the older dancers chose more poses and gestures. Yet there wasn’t a clear generational divide though; dancers of all ages touched hands, or posed beside one another.

But it was third piece, “Fan Dance,” that returned me to the meditative sounds and sweeping shapes of the opener. Thirteen bodies of all types and ages wove through the space in patterns reminiscent of large group social dances. Little solos threatened to interrupt the smoothly shifting lines and curves, but also created our only real glimpses at the grace of each individual. It faded breathtakingly too soon, to hearty applause.

Catherine Galasso’s new piece, “notes on de groat,” placed the choreographer in a corner of the stage seated as if at a desk, an image that drew to mind This American Life or the Broadway Musical, Fun Home. As the dancers perform what she calls “research material” from the show, Catherine narrates her relationship to the dancers and reveals that her father, Michael Galasso, collaborated closely with de Groat as a composer and musician. Indeed it was his moving, expansive music that had accompanied both “Rope Dance and fan dance. Catherine’ s personal storytelling helped me understand why I’d been tearing up during the previous pieces. This dance showcased more than a memories replayed, it showcased the personal dramas of making dance in New York City.

Listening, I began to realize that I don’t have a problem with historical dance or restagings at all. Rather, I can’t support the insistence that only a few chosen voices get to tell our dance history… over and over again. We've erased so many incredible artists’ work. As Catherine explained in her monologue, when Andy De Groat left New York for what would become a successful career in Paris, my generation never learned who he was. This story has echoes of another dancer whose work deeply inspires me: David Zambrano, currently teaching and creating in Brussels with workshops that sell out worldwide. Like Catherine with de Groat, I have the constant experience of mentioning Zambrano to my peers, only to receive blank looks.

In this urban jungle of New York, the moment you stop producing here, new growth comes up taller and faster and blocks out your sun. And all the others struggling to survive here don’t have time to research and discover the foundation laid by others. If we keep telling the same four or five stories, our soil just gets tired and worn. Yet we all know it’s incredibly fertile. So many dancers seed crucial pieces of their work in New York. Why haven’t we celebrated more than those few cash crops?

Producing dance in New York is so hard. Spaces come and go, lose funding, change leadership. It’s a marvel that these dancers not only performed the pieces forty years later, but that they did it in the same space as the premiere from 1978. At another moment, Catherine poignantly mentions that, since she couldn’t afford the rights to screen one of de Groat and Galasso’s own pieces, perhaps we could imagine the scene? That the daughter of the composer can’t even get permission (from a library, no less) to share his work with the public just summarizes everything that is wrong with our current approach to dance archivism. If we lock creativity behind a bank vault, what’s the point of preserving it at all?

Many (especially non-white) cultures have a tradition of listening to elders. And not all elders are celebrities – most are just people in a community that have gained respect through lived experience. In dance, if a performer doesn’t become a dance teacher, then their voices fade quickly into the cityscape of people with interesting stories that might only get captured by chance, in something like the Facebook photo series “Humans of New York”. But the stage is such a great place to amplify those older dancers’ voices. At one point, a dancer physically struggles to keep his mouth to a microphone that is slowly lowered from the balcony. As he wiggles under it on the floor, he reveals pieces of Andy’s correspondence with Catherine during their collaboration to make this show. Her voice in dialogue with his made them both more relatable.

At dinner before the show, my aunt and her friends discussed the new slang that young people were using these days. “What’s ‘FOMO’?” one of them asked. I explained it stands for Fear of Missing Out. Indeed, that night, not unlike most other Saturdays in NYC, I could have seen a number of other shows: I had friends performing at Brooklyn Studios for Dance, Center for Performance Research and Brooklyn Academy of Music. In New York, when you create a piece or plan a dance class, it’s all about getting people to make time for it, getting it to be the thing they can’t skip that night. It’s so hard to make work here at all, and even harder to gather people to see it live. And that’s before even worrying about audiences forty years in the future.

I had to marvel at all the factors that brought me to this unforgettable experience: Ritty, the charismatic performer who inspired her whole meditation group (including my aunt) to come see her dance; my aunt, who decided to bring me along; Catherine, who recreated these dances; Danspace, which presented them; Andy, who created and shared them…and many more. That list of colliding factors underscored for me the incredible fragility of making independent work in New York City and the resulting preciousness of every piece that gets to live for more than one night.

With this program, Catherine, Andy, and the dancers curated an intergenerational conversation on dance archivism. “get dancing” revealed the poetic drama of time, and the personal drama of facing the impermanence of your art form. I am so grateful that I was there to witness this performance. And I can’t help but hope that someone will invite me back to Danspace in 2058, when I’m seventy.

Sarah Chien is a freelance dancer and independent producer with a double life as a UX Researcher. She is the founder of Floor Friends, a network of dancers and teachers, creating a space for contemporary floorwork in the New York City professional dance scene. She writes occasionally about identity, artistic life and travel at www.sarahextranjera.wordpress.com