William Forsythe's "In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated" at 30: Then and Now

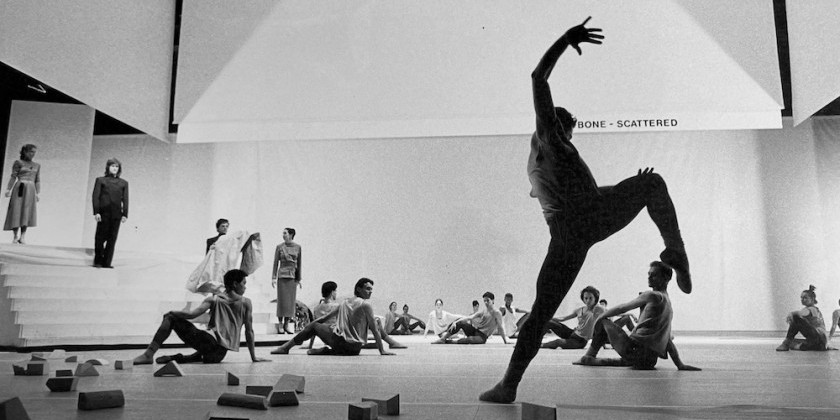

Pictured above: The Washington Ballet in In the Middle Somewhat Elevated; Photo by media4artists/Theo Kossenas

Time defines art, both when it was made and when it is shown. This is particularly true in dance where the constants — steps, music, costume design — don’t always stabilize the variables: dancers’ technical and performative chops, audience sophistication, the political climate.

Dancing in time is no guarantee that the dance will be of the time. Once out of time, a dance risks irrelevance, becoming a curio from days past, interesting for what it was but not for what it is or what it could be. Perhaps great art is great because its constants connect to any time yet stay porous enough to be redefined every time?

When May 30, 1987 rolled around, the old guard of 20th-century ballet was dead (George Balanchine, Antony Tudor) or about to die (Frederick Ashton, Robert Joffrey). The landscape for contemporary ballet looked bleak. Then, the Paris Opera Ballet premiered William Forsythe’s prowling, contentious In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated, the stand-alone second act of what would become the four-act, postmodern ballet Impressing the Czar (1988). The dance world issued a collective gasp. Had the 21st century arrived, thirteen years early?

Forsythe was no new kid on the block. Born in 1949, he began his formal dance training while in college. He joined Stuttgart Ballet in 1973 and became Resident Choreographer in 1976. In 1984, he was appointed director of Ballet Frankfurt where, that year, he debuted the full-length Artifact, the rude angularity and nuanced esotericism of his aesthetic on display.

Over the years, he’s made dances that swing from classicism to experimentalism, but nothing has continued to electrify audiences like In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated. The ballet, with its extravagant athleticism and traditional theme-and-variations structure, is easy enough to appreciate. Yet its enduring appeal may be its telescoping of the global capitalist stage into the fraught, insular one of ballet where self-interest volatizes everything.

The piece opens with two women sizing each other up. A hand rests on a hip; an arch pushes over a toe. Between them lays the scarce, sacred resource of center stage. The battle lines are drawn, the reward clear. For twenty-six minutes, nine dancers (six women and three men) will vie for attention: from you, from me, from anyone who can give it.

Ballet bloomed in the pomp and circumstance of the court of Louis XIV. But beneath the lavishly beribboned costumes and elaborately choreographed mannerisms, courtiers seethed with nervous energy, desperate ambition, and rampant insecurity in their quest to win favor from a fickle king.

A ballet company also functions as a hierarchy where, at will, an artistic director can make or break the dreams of fawning, rabid dancers. While outside the studio the divine right of kings has been guillotined for supposed democracy, virtuosity remains a potent weapon that can slice a bright line between one person and every other person.

Forsythe takes a scorched-earth approach to ballet’s eloquent physicality. He yanks the limbs into obtuse angles (whacking grand battements and thwacking fouettés to arabesque) and flaunts the body’s tips (flexed wrists or a toe supporting a sadistic pirouette en attitude en dehors). Classicism’s refinement is no more than confectioner’s sugar sprinkled over straining, hard-working sinew and bone.

Ballet can be an aggressive act of and on the body. By splintering and then amplifying the vocabulary, Forsythe emphasizes the root — military drills, fencing, do-as-I-say authoritarianism — of its steps: kick, lunge, jump, pivot. Ballet, like life in a capitalist world, is war, with winners and losers, because a spotlight can only shine on a few.

With its relentless, regularly cadenced clangs and wallops, Thom Willems’ electronic score issues imperatives. Work! Produce! Close the deal! When each beat is an emphatic smack, then every action is attacked as important, vital. Therefore, the dancing functions as a moral argument that intense effort and unwavering desire lead to success. Failing is reserved for those who don’t try harder.

Competition for space and time creates alliances that can be abandoned when a better opportunity presents itself. Dancers stride on and off stage, joining in when it suits, leaving when they want. The unity of a corps de ballet appears briefly before being shattered by egos, one and then another dancer breaking away to assert themselves at the expense of the group.

The piece’s multiple pas de deux highlight this self-promotion. The grip — palm-to-palm, like arm wrestling — enables the man and the woman to wrench and shove and twist, to shed any notion that their coupling is romantic. These relationships ate themselves long ago, leaving only antipathy and moments of resigned trust. When it’s dog eat dog, one’s partner is just another asset to exploit.

This lashing violence where the woman’s agency feels illusory but compulsory (she gives where she can, but what she gets is to fulfill the man’s goal of keeping her on one leg, stabilized by his two grounded ones) continues to fatigue some and to energize others.

The ‘80s — reminiscent of the baroque period with its towering hair and rampant, panting ambition — imprints itself in the work. Through the interruptive sequences, the hostile entrances and exits, the prickly autonomy of the performers, Forsythe hints that greed is good, six months before Gordon Gekko explicitly told us so. Yet avarice has a shadow side: humiliation. Resources like center stage and lead roles are limited; disappointment is imminent, inevitable. Thus, aptitude must be exaggerated to secure the literal and figurative limelight.

While the '80s may feel far from our tech-obsessed, content-rich, hyper self-aware age, the divide between haves and have nots is still expanding. As a result, excessive self-absorption may be unavoidable, obligatory even. The much-touted virtues of capitalism — hard work, dedication, aspiration — are the same as ballet, and once employed, personal success becomes just that: personal. When only individual actions count, it’s natural, perhaps righteous, to ignore those in the wings.

Time is a corkscrew, roiling around and around the same themes. From courtiers to ballet dancers, from 1987 to 2017, we’re still negotiating how independence affects dependence. In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated uses the divine lexicon of ballet to expose the worst of striving to be the best. Like a myth physicalized, it can be revisited again and again. What will we take from it thirty years from now?

This analysis is based on Pacific Northwest Ballet’s grainy video of its 2000 performance watched at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and Erin Bomboy's visceral memories.