IMPRESSIONS: Steven Spielberg's “West Side Story" Remake Sidelines Choreography’s Dramatic Voice

full credits for opening image: Mike Faist as Riff, Ariana Debose as Anita, David Alvarez as Bernardo, director Steven Spielberg, andchoreographer Justin Peck on mic., on set of 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY. Photo by Niko Tavernise. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.,

As a mainstream movie-goer, I thoroughly enjoyed the new Steven Spielberg-directed remake of West Side Story, a masterfully-helmed rebooting of the 1961 Best Picture Oscar-winning film version of the landmark 1957 Broadway musical. With a provocatively-detailed screenplay by Tony Kushner, spectacular cinematography by Janusz Kaminski, and production designer Adam Stockhausen’s vivid renderings of lively, diversely-populated city streets, it’s a winning cinematic experience — sure to enthrall drama-loving film audiences, even those who don’t like musicals.

Sebastian Serra as Braulio, Ricky Ubeda as Flaco, and David Alvarez as Bernardo in 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY; photo by Niko Tavernise © 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Yet as a serious fan of the American musical, and particularly its employment of expressive dance, I was disappointed. While the term “musical” is loosely applied to any movie featuring songs, the classic American musical — as both a theatre and film genre — is, at its best, a marshaling of dialogue, music, and dance, in a carefully-calibrated team effort, to put forth entertaining drama. And a large part of what made Broadway’s West Side Story — conceived, directed, and choreographed by Jerome Robbins — such a milestone in musical theatre history was the unprecedented prominence it gave to dance as a conveyor of the drama. The show’s book, by Arthur Laurents -- a reimagining of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, set in 1950s New York City on the contested turf of rival street gangs, the ethnically white Jets and the Puerto Rican Sharks — is a surprisingly short read. The bulk of the stage time is taken up by the powerful Leonard Bernstein/Stephen Sondheim score and the stylized use of dance to tell the story.

Paloma Garcia-Lee as Graziella, Mike Faist as Riff, David Alvarez as Bernardo, and Ariana DeBose as Anita in 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY; photo by Niko Tavernise. © 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

But in Spielberg’s West Side Story, there’s a lot of dialogue. Attempts were made to flesh out the characters, often criticized as stereotypes, by providing detailed back-stories for the ill-fated young lovers, Tony and Maria, as well as biographical specifics about supporting characters. We learn that Maria’s brother, Bernardo, is building a career as a professional boxer; that Tony just finished a stint in jail for almost killing a rival gang member; and, amusingly, that Chino, Maria’s intended, is going to night school to learn accounting but, in sensible working-class fashion, is also studying adding-machine repair. But these specifics, while interesting, bring a sense of realism that makes the overall enterprise feel less like a musical. In place of the stage show and earlier film’s snappy, verbal interchanges seasoned with Beatnik slang, Kushner serves up wordier, more naturalistic conversations, and turns the original’s streamlined storytelling into a talky affair. Sure, it rounds out the characters and may make them more relatable. But characters in musicals often lack dimension. They are intentionally untethered to specifics so they can be employed symbolically to express universal ideas or emotions, which are put forth through music and dance — art forms that speak most effectively to broader feelings, as they lack language’s capability to communicate precise bits of information.

Brian d'Arcy James as Officer Krupke, Rachel Zegler as Maria, Ariana DeBose as Anita, and David Alvarez as Bernardo in 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY © 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

The new film’s musical passages are comparatively short and, with the exception of the riotously rendered comedy number “Gee, Officer Krupke,” are not the movie’s highpoints. They feel like extrapolations, not pinnacles, of the drama, the essence of which is conveyed through acting. Already steered toward realism by its specifying screenplay, the film eschews the heightened aural and physical expressivity of singing and dancing. Its songs are sung not with the larger-than-life sound of classically-trained vocalists — which generates palpable musical excitement -- but with a straight-forward, pedestrian approach that never pushes the performances out of the realistic realm. Instead of bathing us in outpourings of ardor, the yearning “Maria,” as sung by Ansel Elgort in the role of Tony, is musically dull, with the fervor of Tony’s feelings conveyed largely through the reactions of bystanders he passes on the sidewalk.

Ariana DeBose as Anita and David Alvarez as Bernardo in 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY. Photo by Niko Tavernise. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

In most cases, however, the song interpretations are dramatically persuasive, as Elgort is the only misfire among Spielberg’s inspired casting choices. The dynamic Ariana DeBose ignites the screen as the America-touting Anita; Rachel Zegler makes a pleasing Maria; Corey Stoll manages to turn the usually despicable cop, Lieutenant Schrank, into an appealingly perceptive voice of reason; all of the top-drawer dancers playing the Jets put forth hilarious individualized personas, while Mike Faist, as their leader, Riff, emerges as a triple-threat star; and in the role of the macho Bernardo, is a grown-up David Alvarez – remember him? In 2009, he was one of the three talented young boys who shared the Best Actor in a Leading Role in a Musical Tony Award for performing the title, heavy-duty-dance role in Billy Elliott.

Josh Andrés Rivera as Chino and Rachel Zegler as Maria in 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY; photo by Niko Tavernise © 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Yet the great loss, at least for those who revere West Side Story for its groundbreaking choreography, is the remake’s diminished use of expressive dance. This is not to say that its dance sequences, skilfully choreographed by Justin Peck, are not exhilarating. But there’s a sameness to the way each number is constructed and the movement vocabularies are generically theatrical, hardly ’50s period-specific, and not differentiated, inventive, or eye-catching enough to voice anything new or more clarifying about the musical’s dramatic ideas. Regardless of where they begin, virtually all of the numbers open up spatially and overflow onto streets crowded with multitudinous dancing bodies. The choreographic focus shifts quickly away from the language of illuminating gestures, steps, or body actions, and toward the aesthetics of a larger canvas, the group energies, unison moves, and ensemble patterns invigorated by racing cameras that impel the dancers’ journeys up and down sidewalks, or in and around neighborhood markets, stoops, and alleyways. These big swaths of movement drown out the more pointed expression of any individualized move.

Copyright © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Conversely, what Robbins’s choreography (co-created with Peter Gennaro) made memorable — both onstage and in the film version he choreographed and co-directed with Robert Wise — were distinctive body movements that illustrated essential characteristics of the drama’s plot points, characters, and overarching themes. Think of the famous finger snaps introduced in the “Prologue”; the “bull-fighting” Paso Doble moves of the Sharks in “America”; the explosive kicks and the jumps with rounded spines and knees pulled up to the chest in “Cool”; and the grounded, jazzy, social dancing of the Jets, as opposed to the Sharks’ proud mambo-ing in “Dance at the Gym.” To be clear, Peck does utilize and expand on some of Robbins’s iconic movements, but they are not clearly framed, nor repeated enough to register. They get lost, buried amid the abundance of screen-filling activity.

Mike Faist as Riff and David Alvarez as Bernardo in 20th Century Studios' WEST SIDE STORY. Photo by Niko Tavernise. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

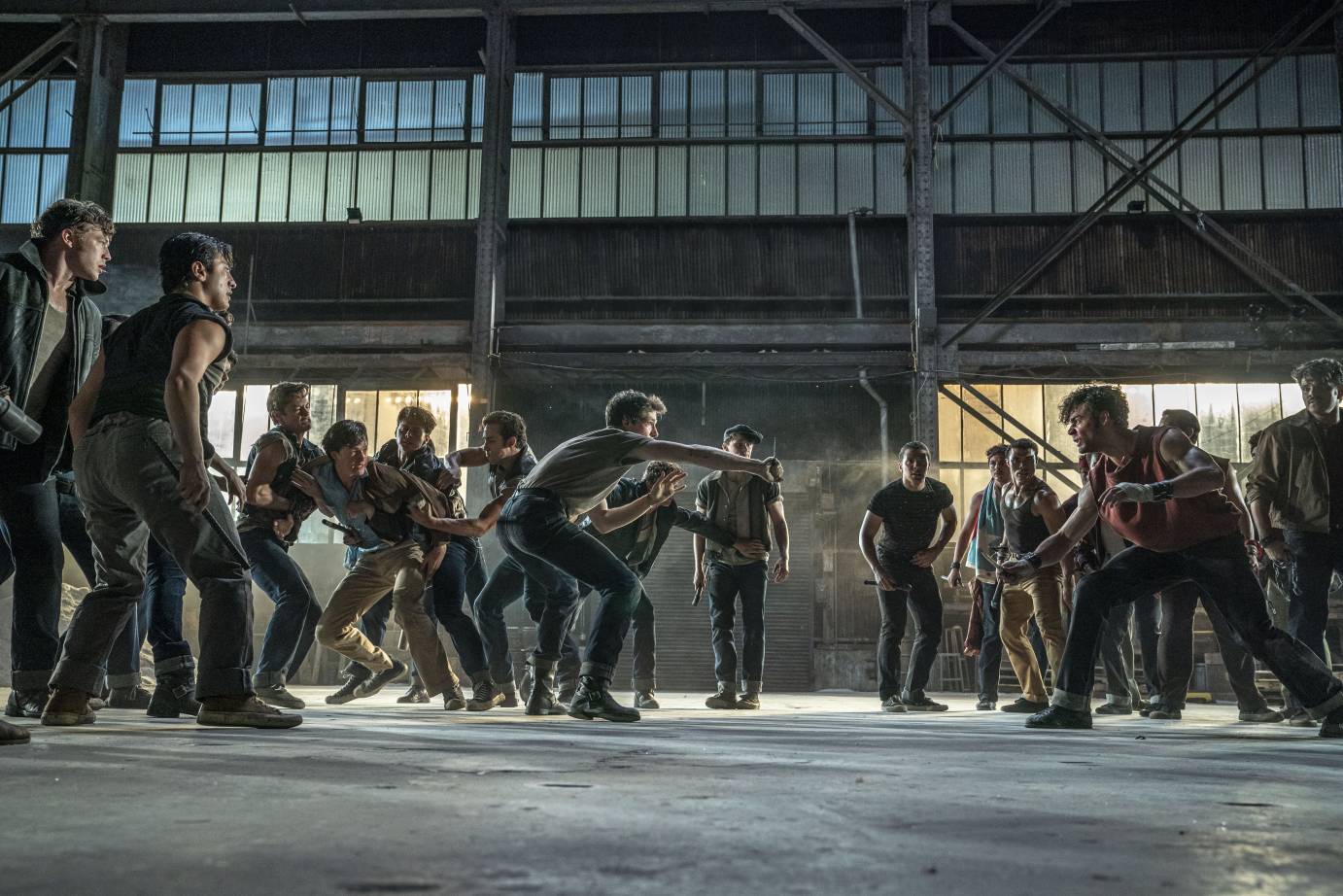

Furthermore, instead of depicting the gangs’ warfare abstractly, through dance — with tense stalking, somersaults, jabs, or balletic spins and leaps, as Robbins did — here we get full-out, down-and-dirty combat that looks as real as an action-movie scene. Granted, much criticism has been leveled against Robbins’s ballet-dancing street warriors, and there are those who find classical dance too arty a lexicon to be dramatically convincing in such a context. So one hoped Peck might have invented a new, more contemporary array of movement vocabularies for the characters in his West Side Story, using dance with the same kind of expressivity that Robbins pioneered. Alas, no. In this re-envisioning of the musical, the singular letdown is that, rather than physicalizing dramatic ideas, dance is reduced to a subordinate role, serving up intermittent shots of energy, tricky athleticism, and visual extravagance.

The Dance Enthusiast Shares IMPRESSIONS/our brand of review, and creates conversation.

For more IMPRESSIONS, click here.

Share your #AudienceReview of performances. Write one today!

The Dance Enthusiast - News, Reviews, Interviews and an Open Invitation for YOU to join the Dance Conversation.

Created in 2020 as a way to lift up and include new voices in the conversation about dance, The Dance Enthusiast's Moving Visions Initiative welcomes artists and other enthusiasts to be guest editors and guide our coverage. Moving Visions Editors share their passion, expertise, and curiosity with us as we celebrate their accomplishments and viewpoints.