IMPRESSIONS: New Adventures/Matthew Bourne’s “Swan Lake” at New York City Center

February 1, 2020

Directed and Choreographed by Matthew Bourne // Music: Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Set and Costume Design: Lez Brotherston // Lighting Design: Paule Constable

Sound Design: Ken Hampton // Projection Design: Duncan McLean

Male swans, same-sex love, repression, and the struggles of a duty-bound royal family created a maelstrom of outrage in 1995 and hurtled director/choreographer Sir Matthew Bourne into the international spotlight. Twenty-five years later, his Swan Lake remains as relevant and powerful as ever. Audiences have not only survived a radical shift in this venerated 19th-century classic, but embraced it. His epic production resonates with universal themes of acceptance, the need to be loved, and the dysfunction that accompanies rejection.

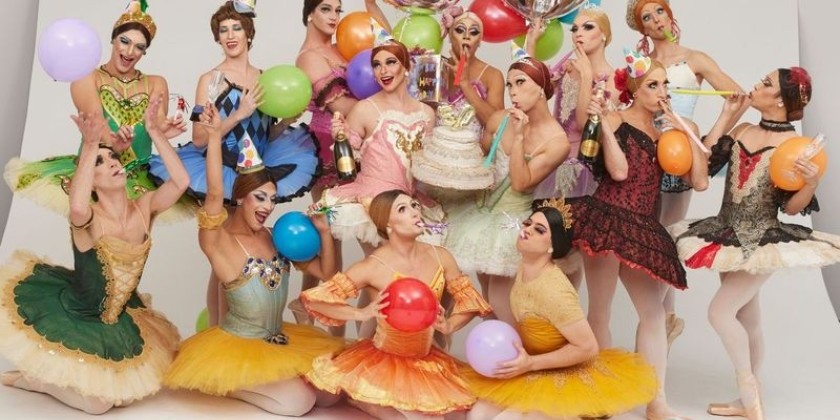

Balancing darkness with humor, Bourne updates the story. Gone is the damsel in distress needing a man’s kiss to save her. Gone is the lighter-than-air, pointe-shoe-clad female swans resigned to their fate. Gone is the cartoonish, motive-less villain of von Rothbart.

Instead, Bourne highlights the strength and aggression of these powerful birds with movements from classical ballet, imbued with a modern twist. Men undulate and take to the air with defiance and joy, their muscles rippling. Their breath resounds through New York City Center as they exhale and hiss.

The cast is skilled as both actors and dancers. Each creates their character from scratch, infusing the choreography with their unique perspective. James Lovell’s Prince is boyish and ebullient, desperate for the affection of his mother. The first scene shows him in the grip of a nightmare. When his mother, the Queen, enters his room, he reaches for her. Flexing her hand, she turns away, and his heartbreaking attempt to grasp her retreating figure sets the stage for his eventual downfall.

Starved for connection, he seeks love in all the wrong places until, unable to endure, he pins a suicide note to a park bench and charges toward his death. Just before he plunges into the lake, a swan (Matthew Ball) blocks his path. Ball is pure masculine power: commanding, sensual, intense. An undeniably magnetic Swan/Stranger, he demands worship. His sultry gaze locks with Lovell’s awestruck one, and their relationship begins.

As the Swan and the Prince grow more comfortable together, they mirror each other with arcing attitudes and sweeping turns. In one yielding moment, Ball cautiously approaches Lovell, wings outstretched, and places his cheek on the Prince’s stomach. With slow neck circles, he caresses him. Vulnerability and desire are palpable.

Ball’s forceful, precise movements make it clear that he remains a wild, unpredictable animal. As row after row of bare-chested man-birds leap around him, the Prince’s surprise melts into wonder, then confidence, which finally erupts in joy. The swans represent all that he, mired in alienating courtly duties, cannot be — bold and free.

In Act 2, Ball swaggers with narcissistic cruelty as the Stranger. Clad in black leather and dripping with salacious intent, he sweeps into the palace ball and seduces everyone, including the Queen. Ball intensifies his technical rigor with scissor-sharp leaps and whipping turns. His public rejection of Lovell is crushing. The Prince’s conflicting emotions drive him to madness, leaving the audience to decide whether the story was the work of his distressed imagination.

The cast, all unique marvels, imbue their characters with distinct quirks and features while maintaining cohesion in the dancing and narrative. Each performer offers a different take, so your experience may change based on the show you see.

The male swan corps is the heart of the ballet, a metaphor for redemption and freedom. They awaken the need for acceptance, and their comings and goings thrill and upset us accordingly. The inventive, provocative gender swap displays the impassioned, animalistic nature of these creatures rather than the traditional model of grace and delicacy. Airborne for the better part of twenty minutes in Act 1, they dance with the defiance of a gay choreographer who lived in England while a law against promoting homosexuality existed. The closing of Act 2 nods to the homophobic violence that is still present today. The birds destroy one of their own, along with his human lover.