IMPRESSIONS: Jamila Wignot’s “Ailey,” a Documentary Film

Director: Jamila Wignot // Producer: Lauren DeFilippo

Editor: Annukka Lilja // Archival Producer: Rebecca Ken

Director of Photography: Naiti Gámez // Composer: Daniel Bernard Roumain

Production Designer: Al Malonga // Executive Producer for American Masters Pictures: Michael Kantor

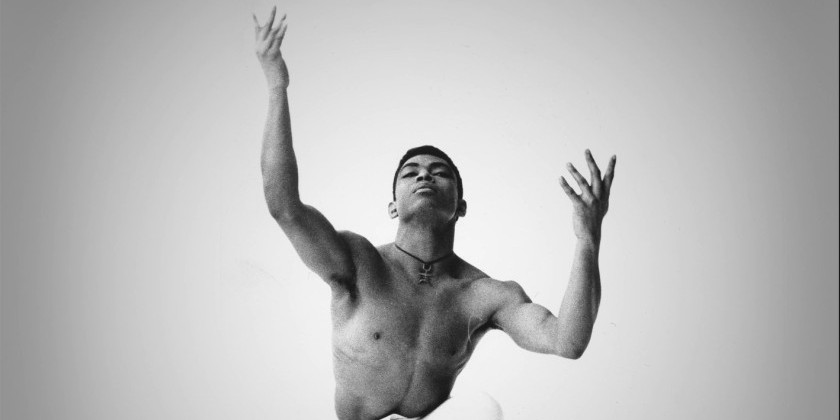

“Sometimes your name becomes bigger than yourself. Alvin Ailey. Do you really know who that is, or what it is? You see a name, but don’t see a man,” explains dancer Carmen de Lavallade, in filmmaker Jamila Wignot’s new documentary, Ailey. A portrait of the eponymous dance artist, Wignot’s meditative film is a precious gift to today’s dance audiences because it spotlights Ailey the man, not Ailey the institution. As de Lavallade suggests, knowledge of the Ailey “brand” abounds — as the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is, arguably, the most widely-known concert dance company on the planet — but even dance connoisseurs, particularly young ones, may know little of Ailey himself.

The framing device Wignot effectively employs throughout the film, to bracket her depiction of the different chapters of Ailey’s life, is rehearsal footage of hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris working with Ailey company dancers on the creation of Lazarus, a 2018 piece, inspired by Ailey’s life and times. While these glimpses of Harris’s rehearsals aren’t terribly compelling, they provide breaks in the biographical narrative that allow viewers time to connect and make meaning from the poetic images and quick interview excerpts Wignot puts forth in her impressionistic approach to telling Ailey’s story. This mosaic-like film is best appreciated by those who already know the basic facts of the company’s history, as less-informed audiences may become frustrated by Wignot’s choice not to communicate such details, in favor of lyrical illumination of the elemental impulses and issues that fueled Ailey’s trajectory.

While Wignot serves up important film clips of Ailey at work, and marshals captivating archival footage to evoke historical context, the tale of Ailey’s life is told, literally, in his own voice, through recorded interviews he gave in his later years. Artfully edited by Annukka Lilja, the documentary walks us through Ailey’s personal journey via his major choreographic works, showing how each piece emerged from the events or concerns of a particular period in his life. Dance history lovers should delight in this strategy because, with the exception of Revelations, it’s not Ailey’s stature as a choreographer that makes him a revered name in the dance world. Hence, his own choreography gets little critical attention anymore. The opportunity to witness Ailey dancing, creating, and coaching his choreographic works is to be reminded of how resonant they once were.

Born in 1931, Ailey, a gay, Black man, grew up in rural, Depression-era Texas, the son of a poor, single mother. He spent his teenage years in Los Angeles, where he was awed by a performance of Katherine Dunham’s Afro-Caribbean-inflected modern dance that, he said, “touched something Texas in me.” In 1954, Ailey moved to New York and, though he studied with the leading modern dancers of the era, he felt he had “stuff inside wanting to get out” — memories of Texas, the sounds of the blues, Southern honky-tonk nightlife, and the rituals and gospel music of Sundays spent in church. These “blood memories” inspired him, in 1958, to create Blues Suite, and, in 1960, his masterwork, Revelations. And so begins Ailey’s monumental legacy of bringing the Black experience onto the concert-dance stage.

As the documentary progresses, we hear from a host of dancers and choreographers who were profoundly inspired by Ailey, and we see how he paved the way for so many of the Black dance artists who came after him. But we also learn how lonesome, sad, and troubled he was. He had only short, intermittent romantic relationships, and his mother, in honor of whom he made the exhilarating solo Cry, in 1971, was the person he remained closest to throughout his life. Supplying the documentary’s most incisive remarks, choreographer Bill T. Jones argues that Ailey seemed plagued by feelings that he was somehow unworthy of his stupendous success. Ailey suffered a mental breakdown and was institutionalized for three weeks. Then he got sick. He asked his longtime muse, dancer Judith Jamison, to take over artistic direction of his company. She knew he was ill, but at the time people were retreating from saying anything regarding AIDS, Jamison explains.

%20Alvin%20Ailey%20Dance%20Foundation%2C%20Inc.%20and%20Smithsonian%20Institution.jpg)

Ailey died in 1989 of AIDS-related illness, and the film ends its story here. However, Ailey’s company, along with its affiliated school, continued to flourish and has grown into a giant force in the dance world that seems to have overshadowed the existence of Ailey himself. Yet Jamison, describing Ailey’s final moments, says “Alvin breathed in and never breathed out. We’re his breath out. That’s what we’re living on.”

Ailey releases in theatres on July 23

The Dance Enthusiast Shares IMPRESSIONS/our brand of review, and creates conversation.

For more IMPRESSIONS, click here.

Share your #AudienceReview of performances. Write one today!

The Dance Enthusiast - News, Reviews, Interviews and an Open Invitation for YOU to join the Dance Conversation.

Share Your Audience Review. Your Words Are Valuable to Dance.

Are you going to see this show, or have you seen it? Share "your" review here on The Dance Enthusiast. Your words are valuable. They help artists, educate audiences, and support the dance field in general. There is no need to be a professional critic. Just click through to our Audience Review Section and you will have the option to write free-form, or answer our helpful Enthusiast Review Questionnaire, or if you feel creative, even write a haiku review. So join the conversation.