Impressions of William Forsythe's Sider

I Hate William Forsythe

Choreographed by William Forsythe

Brooklyn Academy of Music

October 12th, 2013

Light Object by Spencer Finch

Lighting by Ulf Naumann, Tanja Ruhl

Costumes by Dorothy Merg

Sound Design by Dietrich Kruger

Follow Cory Nakasue @CorySpine on Twitter

I love William Forsythe. I hate William Forsythe. I’ve had this back-and-forth with many people, and with myself. His work reminds me of one of those optical illusions—the drawings that look like one thing, but when you refocus your attention, transforms into another image. Only, in the case of Forsythe, the shift in perspective effects my appreciation of the work.

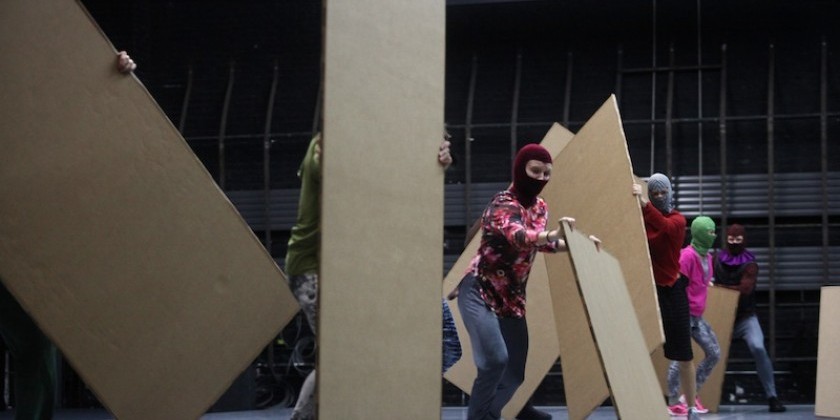

The US premiere of Sider at the Brooklyn Academy of Music this past week is the latest addition to the Forsythe fodder: to love or not to love? Based on the rhythmic inflections of Elizabethan theater, the new piece is a study in sound; the transmutation of all that is acoustic. The piece is also a study in concealment. Sider is dictated by the soundtrack of a late-16th-century tragedy that only the performers can hear through their ear buds. The specific text has been kept a secret. The stage and performers are also obscured by large sheets of cardboard, and the colorful, flickering or fluorescent lights (to great effect).

The consummate trickster of post modern dance confounds with spoken Jabberwocky gibberish and physical verbosity amid a Monty Python-esque tonal palette. Is this theatrical iconography a concession to the audience—a hint, an apology? Forsythe doesn’t compromise. How uncharacteristic. Why such an obvious choice in tone for a piece whose architecture and inspiration is shrouded in mystery? Why not keep your secrets secret?

The classic Forsythe lexicon of movement is still at play in Sider; infinite permutations on “the spiral,” performed with a precision that is scrupulously at odds with its spirit of improvisation. When I think of “classic Forsythe,” I also think of chaotic rhythms that are eradicated by stillness that is so perfect you forget to breathe. These are present in Sider as well.

The closing of the piece bears a striking resemblance to the first William Forstyhe piece I saw live, One Flat Thing. Instead of twenty dancers standing behind twenty large tables, eighteen dancers stand behind their cardboard sheets. They stare out at the audience and drum complex choreographed rhythms on their boards. They are making sound with their bodies, and I can “see” the sound. This is what sound looks like—not what sound means or implies, but this is whatever is coming through their ear buds, looks like.

Kinetically logical. Choreographically illogical. Pure sensation, intellectually amplified. I hate William Forsythe. I love William Forsythe.