THE DANCE ENTHUSIAST ASKS: Francesca Harper on Dancing the Unapologetic Body Into the Future

Christine Jowers for The Dance Enthusiast: Your dance film THAW, with BalletX, Francesca. I couldn’t believe you choreographed that piece remotely. Were you ever in the room with the dancers?

Francesca Harper: No. I choreographed everything on Zoom.

And did you know what you wanted to do when you entered the Zoom room?

FH: No, I both created on the spot and had ideas going into the process. I knew this was an extension of Unapologetic Body, which I've been creating for a few years now — work based on my life experiences. So, I was clear with Ashley and Blake that I wanted them to represent an interracial marriage, my marriage.

I was also thinking about where we are now politically and socially, and as a contemporary artist, I love projecting into the future…

Projecting into the future was a layer in the work — questioning where we are going in terms of humanity and technology and wondering where we will end up. Can we continue to find humanity and intimacy as we move forward through COVID and quarantine? How do we get back to living deeply in intimacy and back to living out our love stories?

What surprised me was how you moved from playing with light, words, and rapidly changing images to this gentle, simple love poem and duet. I was amazed that everything connected. You did it!

FH: I've been choreographing for many years now, you know. It’s fun to figure out how we find meaning and depth and still take risks. That's so important, stepping out on the ledge and not knowing necessarily where you're going. That's been one of the greatest gifts I've received from choreography; you probably know that feeling process when you are writing, right?

You have no idea what you're going to say, then you put the pen to paper and something happens. It’s the same with choreography. You panic. You don’t know what’s going to come next. And then you say, “OK, you’ll walk up to the camera, look into it, and walk back slowly wrapping yourself in the light.”

There it goes. There's the idea. You start to trust your intuition. The pictures and ideas are passing through your intuition, your gut, your heart. You're processing all of that. That's the magic of creating art.

I remember experiencing that feeling for the first time when I was, choreographing at Ailey years ago, I think I had a dream. There were dancers moving up, then sideways, and then down, and then sideways and… I came to the studio the next day and I said, “ OK we have to do this, it came to me in a dream.”

That's the deep and kind of profound channeling and messaging, that the Greeks used to talk about. The artists were seen as being between the gods and the earth, tapping into the unknown.

Have you always felt confident tapping into the unknown?

FH: No, no, no.

I started choreographing in Frankfurt at like twenty-five.

Was that when you were working with William Forsythe?

FH: Definitely. Because he gave us so much room, I thought, “Well, all right, I can create for myself too.” It was wonderful that he was so open, and gave us such agency and such voice.

Was that a different experience for you?

FH: Oh completely, completely different. I was an obedient servant, a soldier of dance up until that moment. I was an obedient muse.

What do you enjoy more?

FH: I go back and forth. I like to be the muse. Sometimes I just want to interpret. As a choreographer, I start to understand why you have to dedicate your life, you know, a life-long journey to creating work. You are subject to deep criticism. If things go wrong, you're responsible for the work. I remember creating and feeling so passionate and getting these really pointed reviews. It was hard when I was younger.

What criticisms did you receive?

FH: It was the times. It took about a decade for contemporary dance to even be introduced into the mainstream. So You Think You Can Dance was one of the first platforms to share what contemporary dance was and conceptual thinking through dance.

I think now these ideas are very much alive. There's a personalization to contemporary dance today which is different from when I was growing up with [for example] Martha Graham. Work was specific; people were developing their own distinct styles and techniques.

Today when I think of some of my favorite contemporary choreographers — Sidra Bell and Andrea Miller — I don't know what they're going to do from one piece to the next. That's exciting. Contemporary choreographers are exhausting the recesses of their imaginations.

As scary as it is to create on Zoom, it’s a new world of possibilities. You can try absolutely anything. “Let's go into the forest and film right there!” It's an unbelievable time if you take advantage and sink into those opportunities. It can be thrilling.

With film, I am in a quiet space when I edit. That for me is very different because usually in tech rehearsals I'm talking to the lighting person and talking to the dancers, trying to coordinate. With film, I can sit with myself and feel. I have a little bit more agency and autonomy over my ideas and my imagination.

When I create for the theater, I always, always, collaborate. The dancers in the moment, in the theater, the work is theirs. They create their own interpretation, and it’s different every night. You give up part of the work to them, to the lighting, to the costumes. There’s a public aspect to creating works for theater.

The film editing process is personal because you're sitting there quietly looking and responding; it’s such a quiet intimate experience.

Do you think you are more in touch with your intuition in a quiet space or in the theater ?

FH: I think the job of any creator is to harness their intuition. There was a piece I created for Erico Iisaku called Look At This Shirt, and it was personal to her and me from the minute that we created the work together. It was work for the theater, but very intimate and intuitive.

As you mature as a person you start to understand how valuable your ideas and your feelings are —especially as a creator. The agency and authorship is recognizing that your feelings, your experiences, your every emotion, thought, and choice, is powerful and can influence the work.

Can you tell me a little bit about how Sleep No More affected you?

FH: Yes, Sleep No More. I tell you, I saw that piece, and it completely changed the way I saw how choreography could or would be portrayed. It was unbelievable. That's when I created my first installation at Ailey. We took away all the banquettes in the downstairs theater and reconfigured them. I created an installation and had my dancers similarly [walking around] with trays, and the audience had to travel. We transformed the theater into a museum gallery space.

I’ve started to realize that for me, futurism, thinking about what's next . . . creating experiences for people is what I am interested in.

What is your idea of futurism and Afro-futurism, how do you see those ideas?

FH: Afro-futurist, any person of color who is willing to tread into the unknown and put their story at the center. We don't know what's going to happen in the future. You take a risk and use your imagination to create images or scenarios that you think might happen. We don't know if they will, or maybe we do. And maybe we start to channel what we see or what we predict.

Because of working with William Forsythe, I'm not fearful of that. He was constantly creating, playing. I remember I was in his piece called The Loss of Small Detail, and it was the first time I had seen film on the stage projected right in the middle of this huge opera house. The dancers had taken a film, it happened in the middle of a piece and . . . I don't know if there was snow falling from the sea . . . It was performance art — really exercising, and exhausting your imagination. That, I think, is exciting.

How different do you find it working in the States compared to working in Europe?

FH: Having worked in Europe for a period of my life, having worked in opera houses where they have that kind of funding . . . I'm so amazed at New York, especially at that level of creativity and how resourceful artists are, but it's difficult.

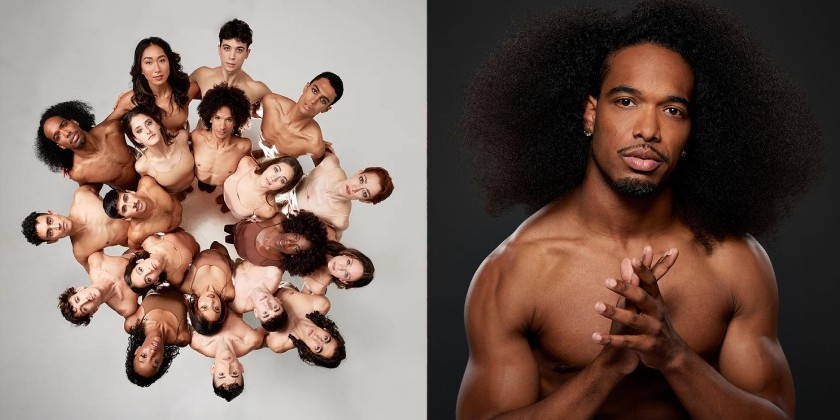

The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, Ballet by William Forsythe;

Dancers in Photo Laura Graham, Noah Gelber, Helen Pickett, Desmond Richardson, and Francesca Harper; Photo Dominik Mentoz

I do wonder why the arts aren't funded more and why people don't appreciate how important arts are in terms of keeping us inspired, keeping us going, enlightening our communities, and our minds.

For five dollars, you could go see the ballet in Frankfurt. In Germany, we had everyone in their jeans coming to see us. Unfortunately, here in America, a lot of the audiences can't afford to go to the ballet unless they buy "standing room" or seats in the 4th balcony.

I think Alvin really had it right, making dances for the people. I was thinking about that today. In the work that I do with contemporary ballet that’s the same philosophy I've taken, ballet for the people, ballet to hip-hop music or to funky electronic scores, so it’s out of the elite realm and has more of a global message.

I’ve never been comfortable with the “dance for the elite” idea. And, you’re not alone, especially now that we are locked in and don’t have any theater. People want to create change and make art more accessible, and affordable. I can only hope this will happen.

FH: Necessity is the mother of invention. I am interested in the future of this new hybrid world. Digitalization will always be part of my programming now.

With your films, you can reach out to people all across the world. They can watch your dances more than once and become familiar with you. Hopefully that can come with touring at some point when we can touch each other again. But, I wanted to ask you about the Unapologetic Body, you’ve been working on this for several years now.

FH: It’s my life, it’s going to take years.

Those two words though, why did you put them together?

FH: This desire for myself to step into my power and understand that my feelings are important, that they will have impact, will leave a mark, an impression on people in the world: my daughter, my husband, my students, my dancers, and my collaborators.

I’m reading your aunt Margo Jefferson’s book “Negroland,” and she writes about your mom, Denise Jefferson, being very skilled at ballet, but being unable to pursue it because there was not a tradition of Black ballerinas.

FH: That was a huge influence. My mom’s story really lived in my heart, and I knew that I in some way wanted to make it happen after she experienced that type of racism. I think I realized from a very early age that I was going to be a ballerina.

I'll tell you my crazy story. You know I grew up around Alvin Ailey, and I went to the Ailey audition in pointe shoes.

Now, why would you do that?

FH: I don't know, that was a sign. Alvin took me into his office after the audition and said “Francesca, I love you. You have a place in the second company, but I think you really want to pursue a ballet career.”

I cried and flung myself into his arms and just said, “You're right Alvin, thank you.” Then I went up to Dance Theatre of Harlem and got a job the next week.

And you say you experienced racism because you didn’t fit into the European standard?

FH: As a woman of color growing up in the ballet world, there was this constant feeling I had to make concessions not to “be too much,” to “fit in,” to straighten my hair, to fit the European aesthetic of ballet. That was challenging.

It’s those moments of being cast in the Nutcracker and being cast as a mouse, as opposed to being cast in the party scene. Or, being cast as a boy Polichinelle, as opposed to a girl Polichinelle. I'm on board of an institution where the girl students of color are constantly cast — if there are no boys available — as boys.

I don't know what that is except unconscious bias. There are biases that live in our world that we've had to battle. The way that I chose, the way I won the battle, was to be much stronger all across the board. To do more turns, legs higher, to be much more proficient and exceptional.

I work with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I've worked with New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. I’ve worked with the Park Avenue Armory. One of my missions is to open up those spaces that have been exclusive, and to make sure that we people of color have visibility and a place in them.

It's so funny with some of those old reviews, honestly, Christine. I remember that I created this work for Dance Theatre of Harlem, and as with most of the ballet pieces that I've created, I was trying to take ballet and craft a new form. [but the reaction was] "We don't want it, we want our ballet dancers to be 'pretty.'"

Desmond Richardson just sent me a picture of one of my first concerts with Complexions. I was in a bra and little shorts on pointe, looking like this warrior princess. You know, there was the ferocity to the work, an almost Martha Graham feminist sensibility — intense, clear, ferocious. That’s what the Unapologetic Body is — my feminism, my strength, my power, knowing when to accommodate, and when not to cower. That’s a lifelong lesson.

Francesca Harper; Photo Nina Wurtzell

Francesca Harper is an inaugural guest editor of The Dance Enthusiast's Moving Visions Initiative. The Dance Enthusiast welcomes artists and enthusiasts to guide our coverage as guest editors. Our guests share their passion, expertise, and curiosity with us while we celebrate their accomplishments and viewpoints. After being named Presidential Scholar in the Arts and performing at the White House, Francesca Harper joined and performed soloist roles with The Dance Theater of Harlem and later as a Principal Artist in William Forsythe’s Ballet Frankfurt. Harper has choreographed for The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Dance Theatre of Harlem, Richmond Ballet, Ailey II, Tanz Graz, Hubbard Street II, and her own company, The Francesca Harper Project, which was founded in 2005 and tours Internationally. Harper performed in four Broadway productions including The Color Purple, then toured in leading roles in Sweet Charity, Sophisticated Ladies, and Lady Day at Emerson Bar and Grill. She also served as a Ballet Consultant for the Oscar winning film, Black Swan. Harper was Movement and Casting Director for The Bessie Award winning, The Let Go, commissioned by the Park Avenue Armory and for Zendaya and Tommy Hilfiger’s Apollo Theater production for Fashion Week in 2019. Fellowships include Urban Bush Women’s Choreographic Center Initiative andThe Ballet Center at NYU. New works include a new creation for Wendy Whelan, Associate Artistic Director of The New York City Ballet and her own autobiographical work, Unapologetic Body, supported by Urban Bush Women’s CCI. Harper is currently engaged as Executive Producer with Sony Pictures on a series in development while also pursuing an MFA in performance creation at Goddard College. For more information, please visit www.thefrancescaharperproject.org

Unapologetic Body is a evening-length dance-theater work currently being developed by Francesca Harper in response to recent global events regarding diversity, inclusion, and empathy (or the lack thereof). After creating, The Look of Feeling, Harper’s acclaimed show about her mother, she realized that her own story needed to be told, but in its own way and on its own terms. The story of the (still unfolding) life of an African-American woman living in the predominantly white worlds of ballet, modern dance, and Broadway, while facing challenges, heartbreaks, and triumphs as she attempts to shatter the stereotypically classical mold and celebrate her evolution into an unapologetic body. Growing up in the Ailey school, being counseled by Alvin Ailey himself, influenced by her mother Denise Jefferson, being a Principal Dancer in William Forsythe’s Ballet Frankfurt, performing on Broadway, forming her own dance company, receiving choreographic commissions and performing around the world; all these influences come together in the creation of Francesca Harper’s Unapologetic Body. Ultimately, Unapologetic Body will develop into a full-length immersive work with 1- 4 performers utilizing dance, music, and narrative. Run time: evening-length, exact timing tba, work in development.

Created in 2020 as a way to lift up and include new voices in the conversation about dance, The Dance Enthusiast's Moving Visions Initiative welcomes artists and other enthusiasts to be guest editors and guide our coverage. Moving Visions Editors share their passion, expertise, and curiosity with us as we celebrate their accomplishments and viewpoints.