Impressions of: ROYAL DANISH BALLET at The Joyce Theater

Principals and Soloists Reveal A Balance of Tradition and Invention

The Joyce Theater, NYC

January 13 – 18, 2015

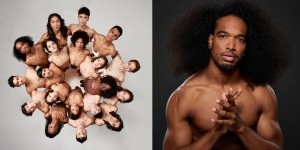

A small group of thirteen principal and soloist dancers from The Royal Danish Ballet appeared at New York City’s Joyce Theater with a selection of works by one choreographer: August Bournonville.

What was it about the program that made me elementally happy? A repertoire spanning four decades of the mid 19th century (1836-76) brought innocent yet memorable facets of joy, comradeship, and community on stage. The dancers presented all of these with technical mastery and performed with inspired enthusiasm. The second act of the Romantic masterwork La Sylphide from 1836 added some drama and darkness to the otherwise cheerful atmosphere.

Organized by dancer Ulrik Birkkjaer and briefly introduced by Danish historian Erik Aschengreen, the program was convincing without any sets, hardly any props, and no corps de ballet. The spice was in the steps. The mostly vertical nature of the work — lots of jumps with intricate fast beats of the legs — was well suited to the small stage. Rhythmical footwork by the supporting partner created a marvelous counterpoint to the lightness of the one being supported. The delightful use of épaulement made it seem the dancers were not only in conversation with one another, but each one’s upper half listened to the intricate choreographic patterns the feet so brilliantly traced and defined. It helps that in many of their airborne phrases, the Danes bend from side to side with supple vibrancy.

After having seen the Paris Opera Ballet’s original production of La Sylphide in 1834, two years after its premiere, ballet master and choreographer Bournonville created his own version in Copenhagen in 1836. Set in the Scottish highlands, the ballet is a staple of the Danish repertoire. James unwittingly crushes the spirit of the Sylph by wrapping a scarf around her. The demonic Madge, played here by Sorella Englund, poisons the scarf and convinces James that he could capture and keep the Sylph with it. Gudrun Bojesen in the title role and Birkkjaer as James are engaging. Bournonville’s choreography is the perfect mixture of meaningful gesture and virtuosic dancing that propels the plot. (To get an idea of the beauty of this ballet, please click here for an excerpt of my favorite Sylph, Eva Evdokimova, who was the first foreigner to join the Royal Danish Ballet in 1966. She dances with Danish-trained Peter Schaufuss in his 1979 production of Bournonville’s La Sylphide with London Festival Ballet.)

But Scotland is only one of the many destinations that the evening takes us. The wedding pas de sept from A Folk Tale (1854) opens the program on Danish turf with exuberant high-flying leaps and introduces the fancy footwork that must be one of the reasons why I leave the theater deliriously giddy. Another reason for my happiness is the sense of democracy that is displayed in many of the excerpts that let one take a trip around Europe in two hours. This seems to be proof that ballet has been and can be a communal folk tale and does not have to be bound by imperialist hierarchical structures of the post-Bournonville so-called classical and neo-classical styles of a Petipa or Balanchine.

Ida Praetorius and the dashing Andreas Kaas invite us to The Flower Festival in Genzano. This gem from 1858 is always inventive and surprising in its partnering: the lady even supports her man at times. This flower festival is a Danish translation of Italian merriment and the message I get is a celebration of equality in which each participant makes expert use of one’s strengths. Sebastian Haynes and Marcin Kupinski compete with marvelous one-upmanship in the "Jockey Dance" from From Siberia to Moscow (1876). The exactitude in execution is thrilling, but what made my heart flutter is the playful glee with which Haynes peppered his phrasing.

After intermission, Bournonville bows to the French tradition in the pas de trois from Conservatoire (1849), the most academic of the evening’s offerings, but by no means a dry one. The finale of this welcome extravaganza is Act 3 from Napoli (1842) with music by H.S. Paulli, who also composed “Flower Festival” and “Conservatoire.” The Danish Southern Italian charm is jubilant and performed with purity by the splendid cast. While the women of the company are lovely, it is the men — Birkkjaer, Kupinski, Haynes, Kaas and the equally dazzling Gregory Dean — who are the best advertisement for a trip to Copenhagen.

One hopes that Nikolaj Hübbe, the artistic director of the chamber troupe’s mother company, The Royal Danish Ballet, balances tradition and invention in a visionary way. This program certainly peaked my curiosity for further investigation.