IMPRESSIONS: Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in “Deep Blue Sea” at Park Avenue Armory

September 26, 2021

Creator & Director: Bill T. Jones

Choreography: Bill T. Jones, Janet Wong, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company

Performers: Harrington Hinds, Dean Hused, Jada Jenai, Shane Larson, S. Lumbert, Danielle Marshall, Nayya Opong, Marie Lloyd Paspe, Jacoby Pruitt, Huiwan Zhang, Bill T. Jones and community participants

Visual Environment, Video Projection & Lighting Design: Elizabeth Diller, DS+R, and Peter Nigrini

Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel

Composer & Music Director: Nick Hallett

Electronic Score: Hprizm aka High Priest, Rena Anakwe, and Holland Andrew

Sound Design: Mark Gray

Dramaturg: Mark Hairston

Vocalists: Jay St. Flono, Phillip Bullock, Shaw Hester, Prentiss Mouton and Stacy Penson

Deep Blue Sea by Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company at the Park Avenue Armory is a masterclass in how to return from a pandemic, brighten the dim optimism for the future of Black lives, and unveil a body of work that disrupts comfortable, passive activism. The lighting, visual environment, and sound design break every expectation; cohesively, they discovered the most effective way to shape, maneuver, and reflect the shifting ground society currently stumbles on.

How does it feel to be a problem?

We enter the space walled off by bleachers. The crowd is corralled into lines waiting to board our seats, designated by four cardinal directions: North, East, South, and West. Heading to the north section, I come to a corner with an opening. Before us is blonde wood flooring the length of a soccer field. We’re instructed to walk across the stage diagonally to the opposite corner.

It feels like entering the arena of Gladiators. Walking through the center of the stage shifts my experience to that of a runway and I become self-conscious with nowhere to run. “If you’re going through hell, keep going,” said Winston Churchill. Breathe.

The cover of the brochure in our seat reads “How does it feel to be a problem?” This is the question we have to sit and wrestle with. Taking in the arena, I notice that the floor is extremely bright and lit only by fluorescent lights. Bill T. Jones is stopping in the same seven areas collecting his physical phrases. As the last people enter and cross the space, I remark how well everyone is dressed: gowns and three-piece suits — this is a next-level theatre audience.

Jones suddenly begins to speak deconstructed text. It’s a song I don’t immediately know the title of, but eventually, I recognize words. “Let Freedom Ring” by Francis Scott Key. As his voice and Black body moves within the space reciting this text, I find an unvoiced breadth of truth. The meaning conforms to his body and experiences. It reminds me of learning about the third verse in The Star Spangled Banner, the racist underpinning in a song meant to ignite national pride.

“I don’t remember,” admits Jones. He has shifted to an anecdote about how he was introduced to Moby Dick, written by Herman Melville, as a schoolboy. Reading the book again many years later, he wondered, “Why is Pip invisible to me?” He had forgotten about this young African-American boy who cleaned the ship and entertained the other crewmates by playing his tambourine. How could he forget — erase the one character who was most familiar to him?

I’m considering the calculated and continued erasure of Black peoples throughout histories. A lens that the dominant voice uses to frame people of color, denying their full existence except in withered tropes and stereotypes. Without culturally relevant, responsive, or sustaining education what do schoolchildren learn of indigenous and people of color?

Jones pulls back to the edge of the stage as two disciples enter the space from opposite corners. Both Black women mirror each other until they meet in the center of the arena. Using the phrases Jones collected before, they create a moving picture like a stop-motion reel. The remaining eight disciples enter in duets, coupled by their race, on opposite ends of the arena. They form an assembly line rotating through the seven spots assigned by Bill T. Jones, and when they stop, they create tableaus that are simultaneously beautiful and uneasy.

In an instance, a Black woman cowers upon the floor as a white man snaps his finger and points down at her — the status between the oppressor and the subjugated. The disciples continue, alternating between Asian and Black, Black and White, Woman and Man, Cisgender and Transgender.

“The rules were made to protect those who feel violated. The rules were made to protect those who are violated,” the disciples repeat in chorus. The friction between the two statements demands pause to consider the alternative words “feel” and “are.” Striking how much semantics and labels can determine your fate. What are the rules, who made them, and why must we follow them? Who’s protecting me? “I don’t remember.”

Jones recounts how Pip was left out at sea after the second time he jumped out of the boat. When Jones stops and speaks, a black spotlight, not like anything I’ve ever seen before, beams onto the floor creating a black circle around him. The rest of the floor remains blonde. “Brilliant Black spot,” he proclaims of Pip, although in manifesting this visual metaphor, Bill T. Jones is the Brilliant Black spot.

Jones walks along the edge of the stage and everything goes dark. The floor falls out from beneath us and the projection of a magnificent blue ocean sweeps in. Crests of waves flow across the floor and are reflected in mirrors attached to the front of the bleachers. We sit, overcome with the sound of waves rolling through the space.

I’m anxious to know how long we will be in the water. Is this what Pip experienced when he was floating in the ocean? I don’t want this peace to end. The next passing wave brings with it a flood of hard truths and gentle nostalgia. Tears well up behind my eyes. Again, “How does it feel to be a problem?”

The live choir delivers a spiritual gospel from the east, and the face of a young Black boy is projected on the arena floor, a nod to Pip. The master of ceremonies delivers his lyrics with rhythm and rhyme unapologetically. Glitches begin to distort the face of the boy. I wonder how many Black men, women, and children have died whose names have not been recorded and remembered.

As disciples re-enter, three are immersed in a choral song leading the group into a crescent formation. Strewn across the floor from lying to standing, all are connected by touch, reaching toward a distant future we cannot yet see. They line up along the edge of the stage. The first disciple leads the second into the space, and they begin rehearsing segments created by Jones. The second calls for reinforcement “I need you!” When all the disciples have joined, one shouts “Are you satisfied?” The rest respond “No!” and rush to a different location in search of refuge. This continues as Bill T. Jones lists the names of Black civil rights activists who were either assassinated or banned from history books because they were "a problem." Projections of red splatter across the floor.

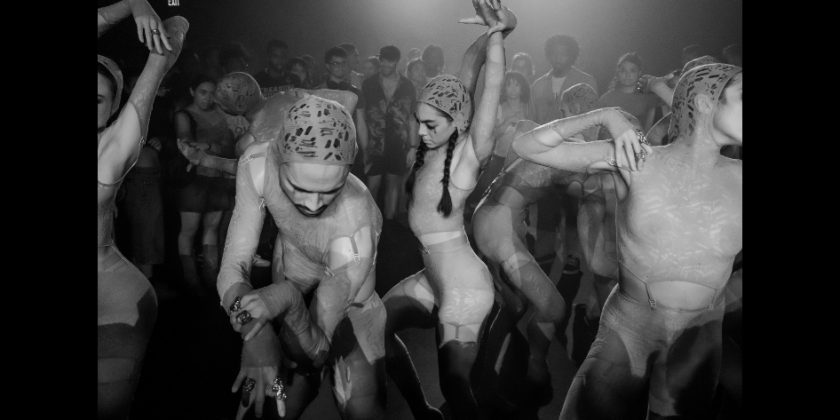

A large group of community members is led into the arena, their path tracing the shape of an infinity sign with the same collection of physical phrases. The disciples pass on their wisdom to the community — “Each one Teach one.”

As the community continues on one side of the space, on the other, Jones holds a live-stream camera in the face of his disciples that is projected onto the floor. We see their faces up close sweating, trying to control their breath, making brief eye contact with the camera. Jones interrogates them, “What do you know?” They say nothing.

The group swarms the arena and they lie down next to each other on their backs covering the length of the middle of the floor. They begin to rock back and forth, like bodies being stowed in the belly of a ship. We are observers onboard the American Melville.

Messages from the Deep Blue Sea will continue to surface as time goes on; at times an unwanted self-reflection, but necessary for understanding, empathy, and re-establishing a torn and disillusioned community. I will remember the authority in Jones’s voice, that of a Griot navigating the dark depths of truth and challenging the listener to relocate and reckon with their perception of self.

The work's intelligent reexamining of a classic American novel takes courage; there is no pleading with or seeking permission from the audience. Experiencing this work of art at the helm of Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in Park Avenue Armory in 2021 sparks inspiration, joy, caution, and hope. Is Bill T. Jones now a problem?